Physicist, Ergodicity Economics @LdnMathLab, @sfiscience.

Book: https://t.co/Ud4s4YSGD0

7 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

https://twitter.com/PeterMcCormack/status/19991924954695721582/

2/

2/

2/

2/

This work soon attracted the attention of some extraordinary thinkers. I had met them because we were all members of the community around the Santa Fe Institute @sfiscience. Among them were Murray Gell-Mann, Ken Arrow, Reuben Hersh, and Cormac McCarthy.

This work soon attracted the attention of some extraordinary thinkers. I had met them because we were all members of the community around the Santa Fe Institute @sfiscience. Among them were Murray Gell-Mann, Ken Arrow, Reuben Hersh, and Cormac McCarthy.

2/

2/

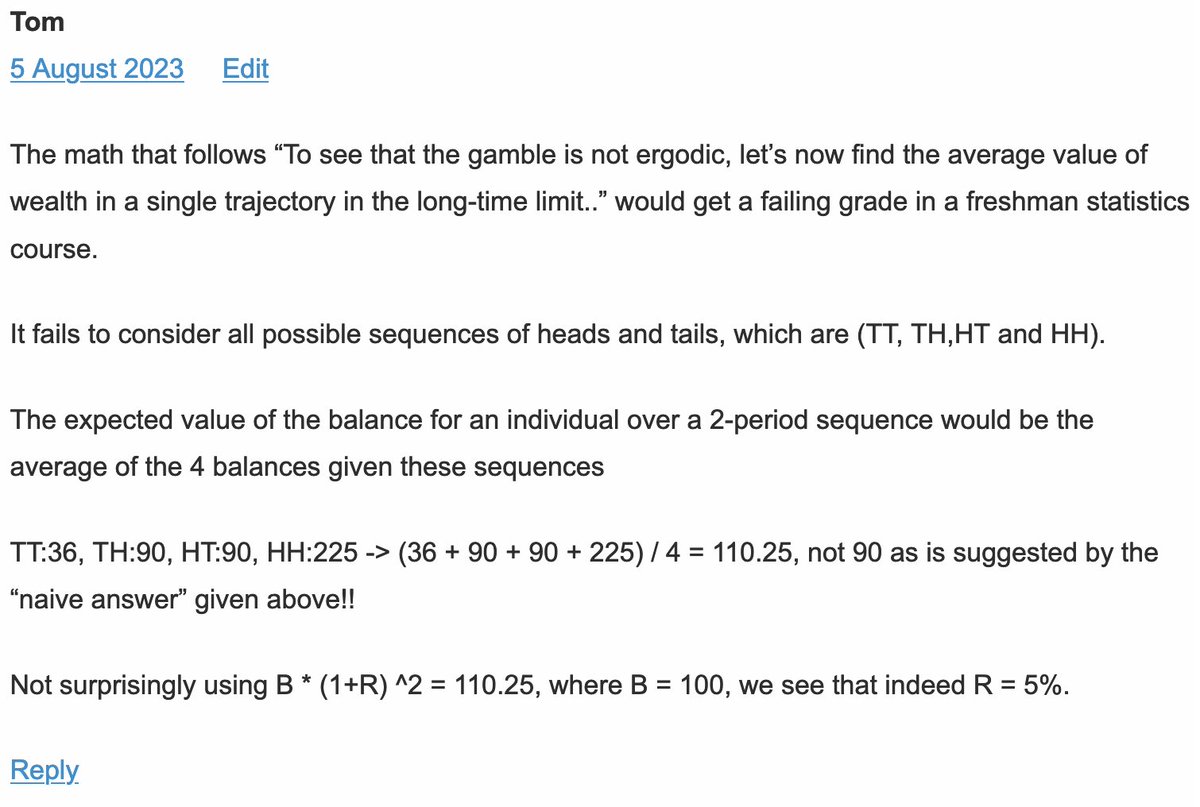

Update: Tom is still rather angry. He has now worked out how to compute expected value.

Update: Tom is still rather angry. He has now worked out how to compute expected value.

https://twitter.com/ole_b_peters/status/16598234607538503682/7

https://twitter.com/philipcball/status/1579506011358244865I know that the financial sector is sort of non-existent in a general competitive equilibrium view of the world. Ken Arrow listed it as one of the failings of economics: that finance shouldn't really be there but clearly is. Did they discover the financial sector for economics?

2

2

...by Annalen der Physik - yes, the journal which publishes the Physics Nobel Lectures - to write a review article on Ergodicity Economics. So I'm using all my channels to find out what people have done.

...by Annalen der Physik - yes, the journal which publishes the Physics Nobel Lectures - to write a review article on Ergodicity Economics. So I'm using all my channels to find out what people have done.

2/5

2/5

https://twitter.com/TheShubhanshu/status/13412535156085473282/7

2/

2/

2/9

2/9