Medicaid is only one of the glaring omissions in this @washingtonpost article.

The other is a misleading portrait of a "struggling rural hospital." It is simply incorrect to present this hospital (Poplar Bluff) as an example of the challenges facing rural facilities.

1/n

The other is a misleading portrait of a "struggling rural hospital." It is simply incorrect to present this hospital (Poplar Bluff) as an example of the challenges facing rural facilities.

1/n

https://twitter.com/ddiamond/status/1163094978450591744

Start with a reality check on hospital closures. In recent years, we've seen 15-25 hospitals close each year (18 in 2017, 15 in 2018), and 5 - 15 new hospitals open each year.

Which is to say, the number of American hospitals declines, on net, by about 0.2 - 0.3% each year.

Which is to say, the number of American hospitals declines, on net, by about 0.2 - 0.3% each year.

It is debatable whether rural areas actually see a disproportionate share of those closures. In 2017, for example, rural counties hosted 48% of the general acute care hospitals in the U.S. and saw 44% of the closures (8 out of 18).

gao.gov/assets/700/694…

gao.gov/assets/700/694…

**To be fair, none of the five new hospitals opened in rural areas in 2017, and of course there is a big difference between a community that goes from 1 hospital to zero, and a city going from, say, 5 hospitals to 4.

So, @elisaslow's point of departure here is flawed.

Regardless, it is entirely misleading to suggest that Poplar Bluff exemplifies a rural facility "on the brink of insolvency...[fighting] to squeeze whatever money they’re owed from patients who don’t have it."

Let's dig in...

Regardless, it is entirely misleading to suggest that Poplar Bluff exemplifies a rural facility "on the brink of insolvency...[fighting] to squeeze whatever money they’re owed from patients who don’t have it."

Let's dig in...

First, Poplar Bluff Regional Medical Center is not small, not under any unusual financial pressure, and the facility is quite profitable.

To be precise, Poplar is a ~220 bed facility with ~60% occupancy. Average across the U.S. is closer to 150 beds and 45-50% occupancy.

To be precise, Poplar is a ~220 bed facility with ~60% occupancy. Average across the U.S. is closer to 150 beds and 45-50% occupancy.

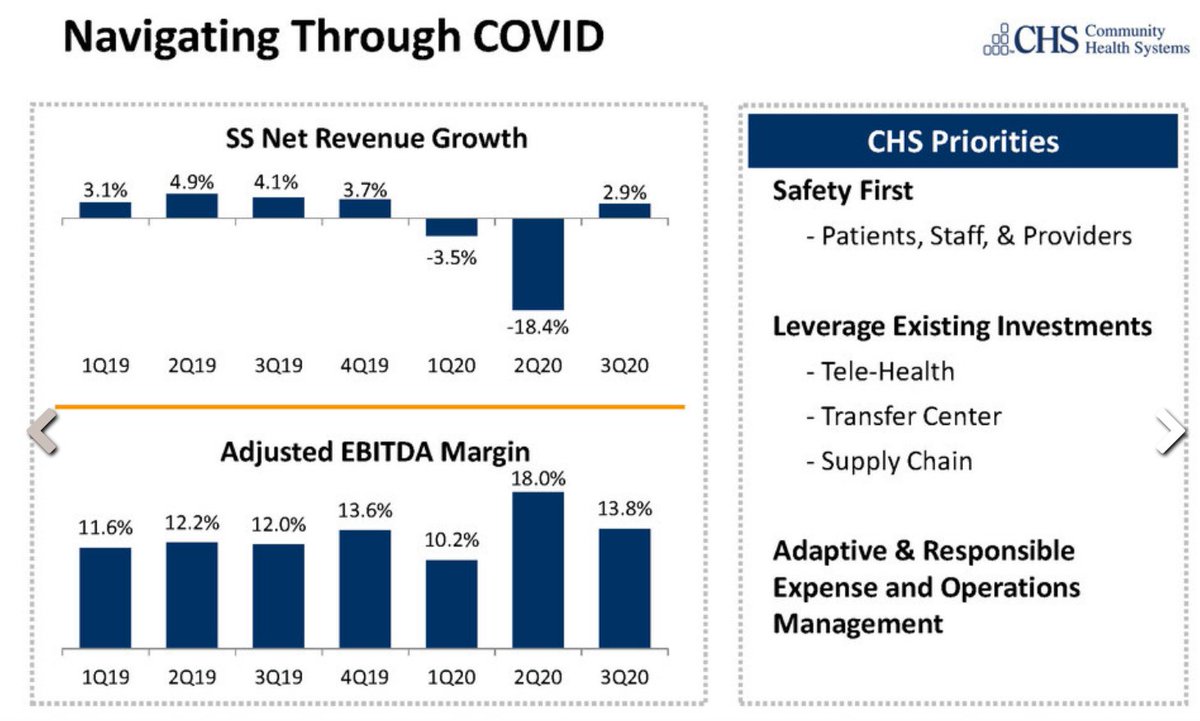

And, on the hospital's own data,* Polar enjoys a very healthy 13.8% operating profit margin on >$200M in revenue. A typical 200-250 bed for-profit hospital runs at an 8-9% operating margin.

*See HCRIS, as compiled by RAND.

*See HCRIS, as compiled by RAND.

Second, Poplar is part of Community Health Systems, a for-profit chain with some of the highest prices in the country.

Considering both inpatient & outpatient, CHS charges private patients 305% of Medicare, which is nosebleed territory. Nationwide, that beats all but 9 chains.

Considering both inpatient & outpatient, CHS charges private patients 305% of Medicare, which is nosebleed territory. Nationwide, that beats all but 9 chains.

Now, this gets really interesting when you consider that Poplar itself states that it enjoys a 4% profit margin on Medicare patients.

Take that in... We serve 70 yr-olds profitably at $100, but we charge 50-year olds $300. And then take them to court if they don't pay in full.

Take that in... We serve 70 yr-olds profitably at $100, but we charge 50-year olds $300. And then take them to court if they don't pay in full.

Finally, while there is clearly no need for Poplar/CHS to "squeeze whatever money they're owed from patients who don't have it," it is also unlikely that these lawsuits will even have a material impact on CHS financials, where only ~1% of revenue comes from patients themselves.

To be sure, rural residents often struggle to access high quality care. But we are not going to understand those problems by focusing on the travails of a large, highly profitable hospital w/ monopoly pricing power, which has decided to sue its own patients for no good reason. /n

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh