Today in pulp I’m looking back at one of the many 1950s British imprints who rode the post-war publishing boom: Badger Books! #SaturdayMotivation

John Spencer and Co was founded in London in 1946 by Samuel Assael and specialised in publishing original fiction, normally written to order by freelance writers using house aliases. Like many pulp publishers they paid a flat rate for copy – ten shillings per 1,000 words.

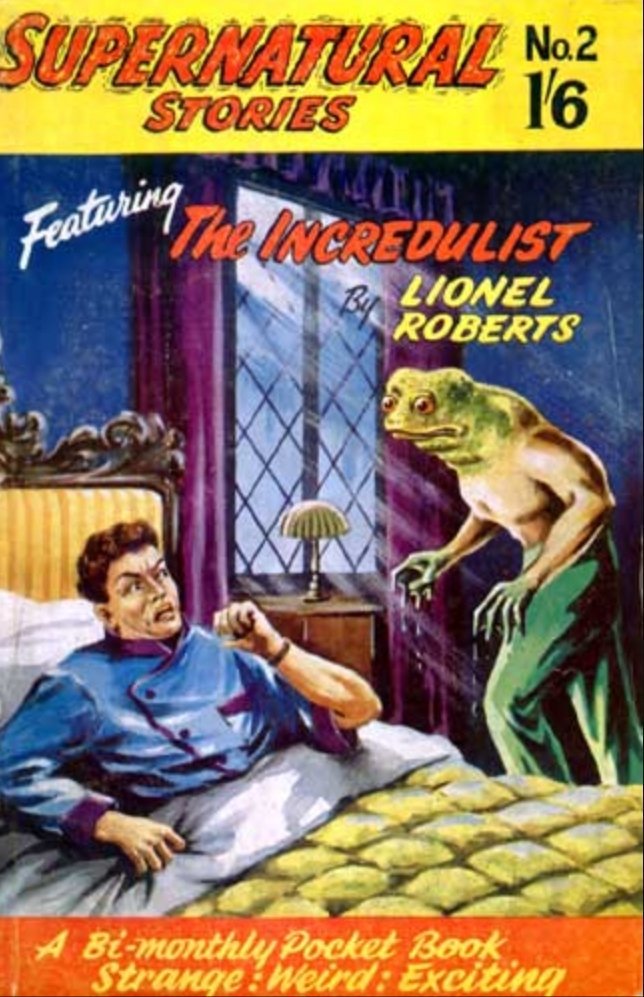

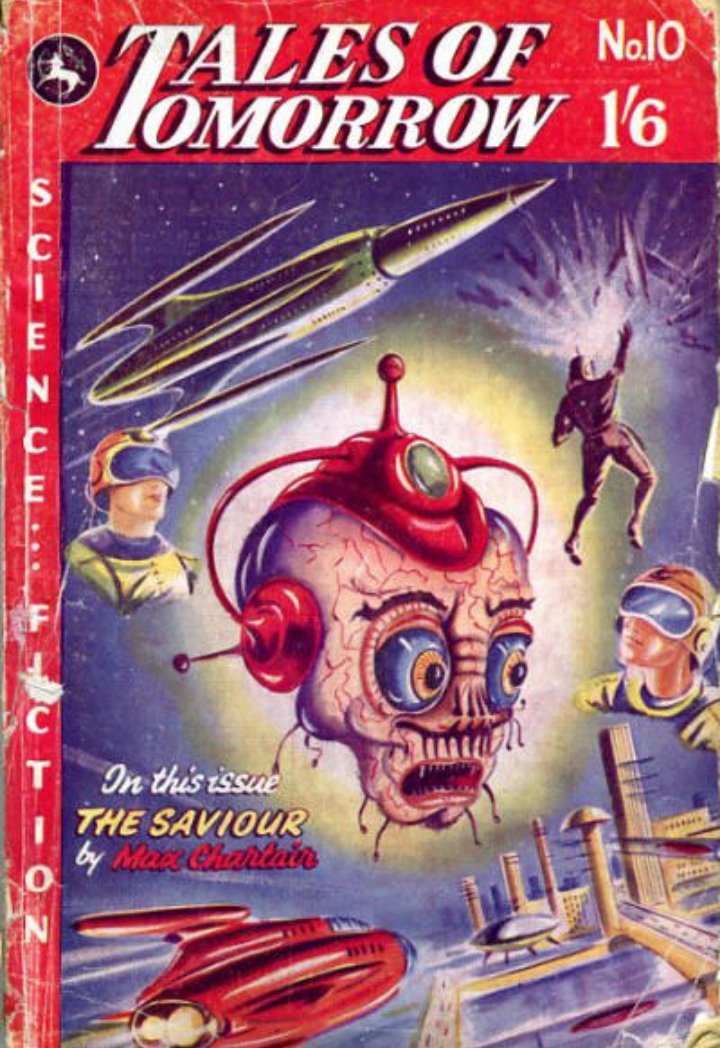

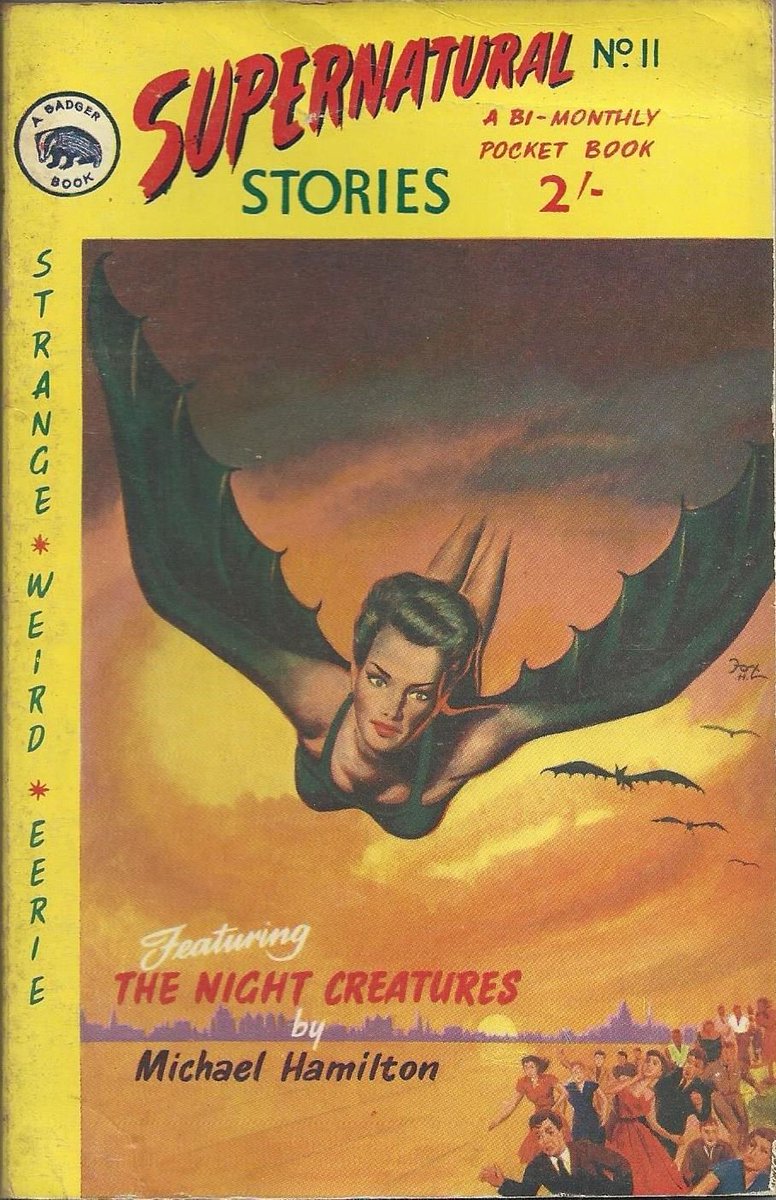

Initially Spencer focussed on story magazines in digest and pocketbook form: Tales of Tomorrow, Out Of This World and Supernatural Stories focussed on fantasy and sci-fi short stories. But the digest market was beginning to decline as the post-war paperback market began to boom.

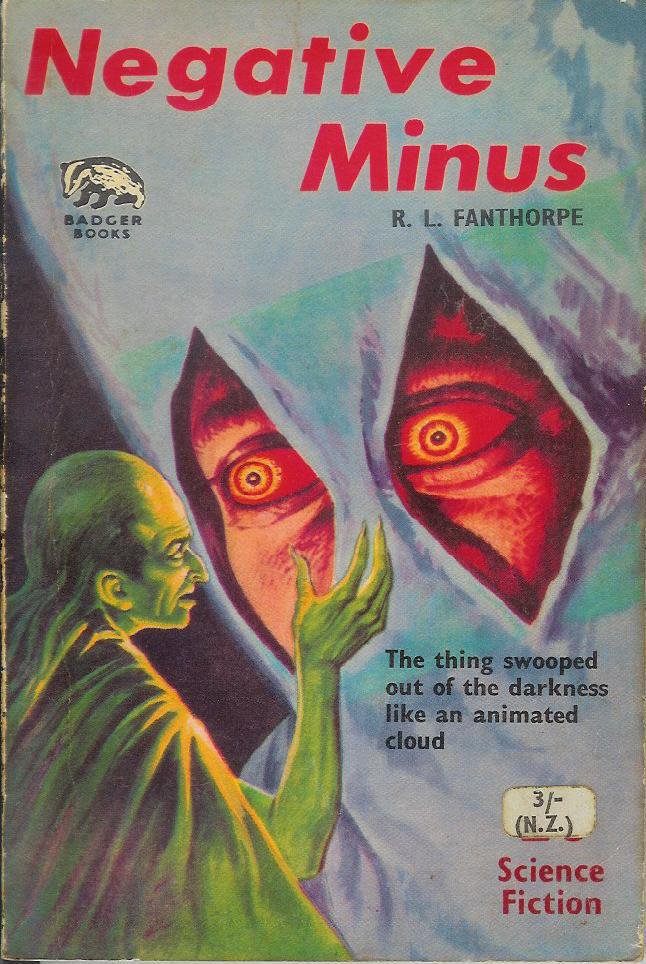

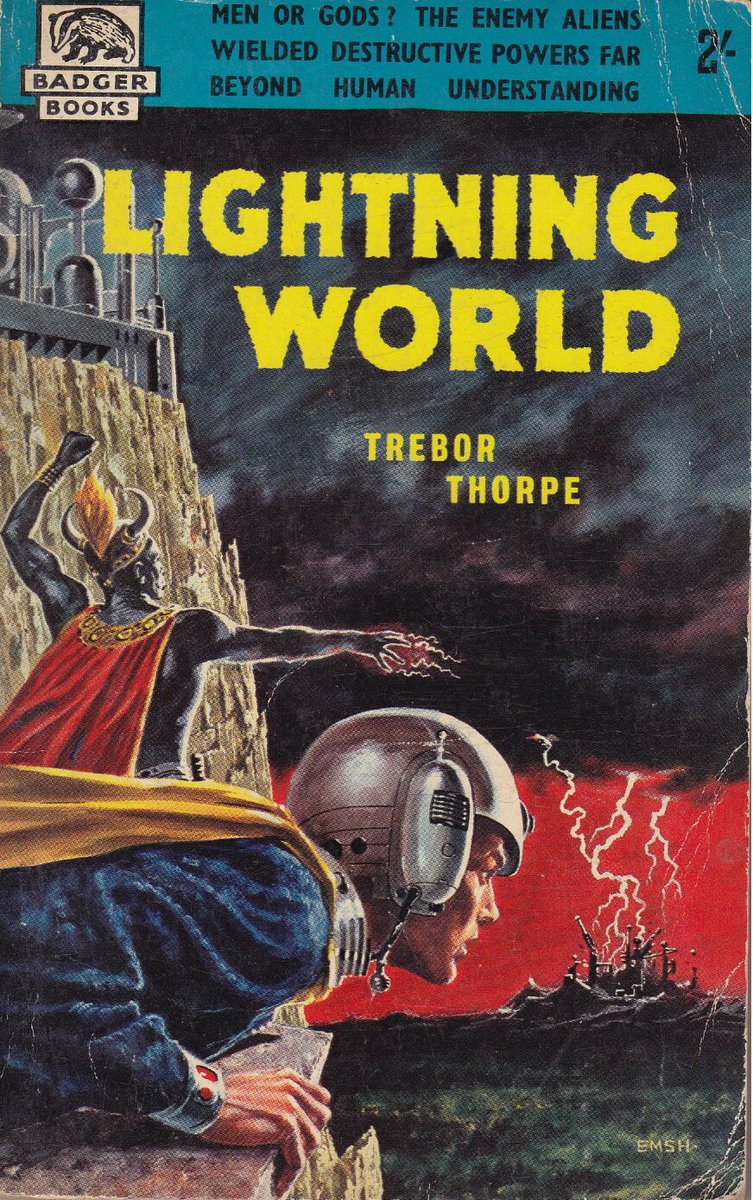

So in 1954 Spencer tool the plunge and set up its own range of original paperback novels: Badger Books. Run from small offices in Hammersmith, London, half a dozen staff and two principle freelance writers managed to produce over 580 original books over 13 years.

Badger Books existed to fill a need: an insatiable desire for something cheap and original to read – preferably in book form – that was gripping Europe and the US after the war. An economic boom, a greater focus on leisure and an end to paper rationing had fired up the market.

Just as important were the hundreds of thousands of demobilised servicemen who had grown used to having cheap books to read during wartime and carried over the habit of reading into civvy street. The book buying market expanded at the same time that entry costs dropped.

That meant publishers like Badger needed stories – lots of them! They needed to publish a range of new titles every month at least. And the amazing thing about Badger was just how much of their output came from two amateur writers from very different backgrounds…

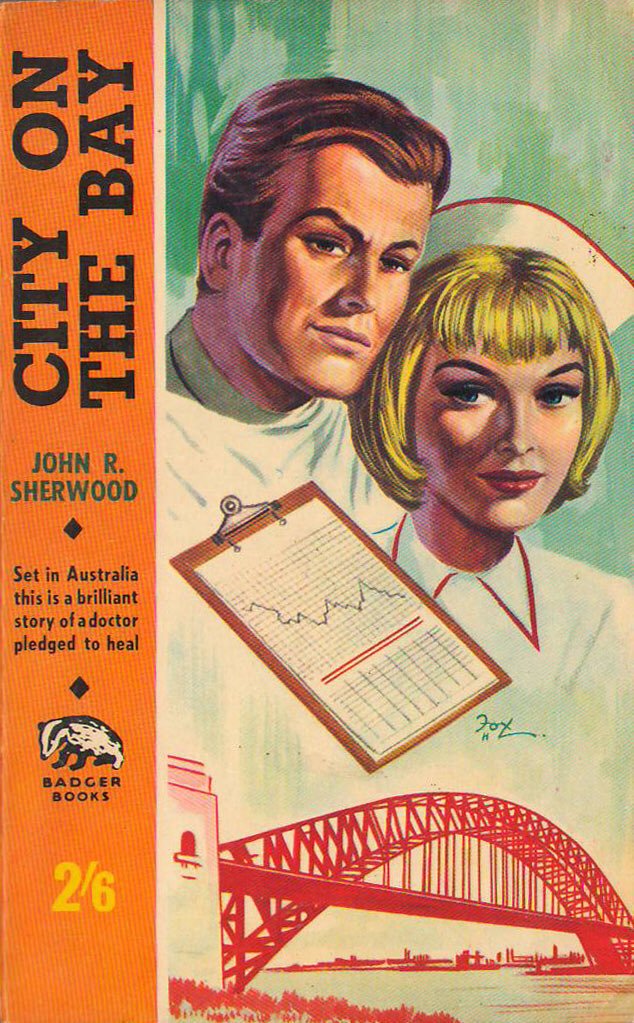

John Glasby was a research chemist for ICI, carrying out research on detonators and rocket propellants, when he began a side line in writing for Badger Books. Overall he had 300 stories published, covering western, sci-fi, spy, detective and hospital romances.

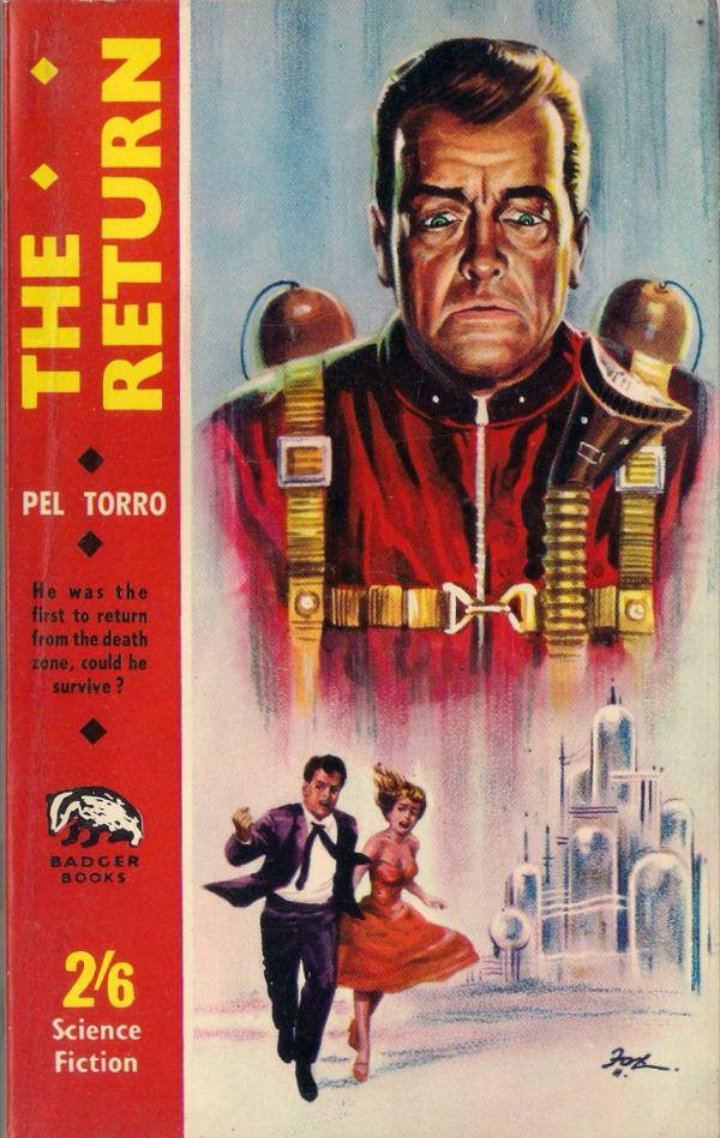

The Reverend Lionel Fanthorpe sold his first story to Spencer aged 17, and in between various other jobs he produced over 160 stories for Badger Books, mainly sci-fi and supernatural tales, sometimes produced in as little as three days.

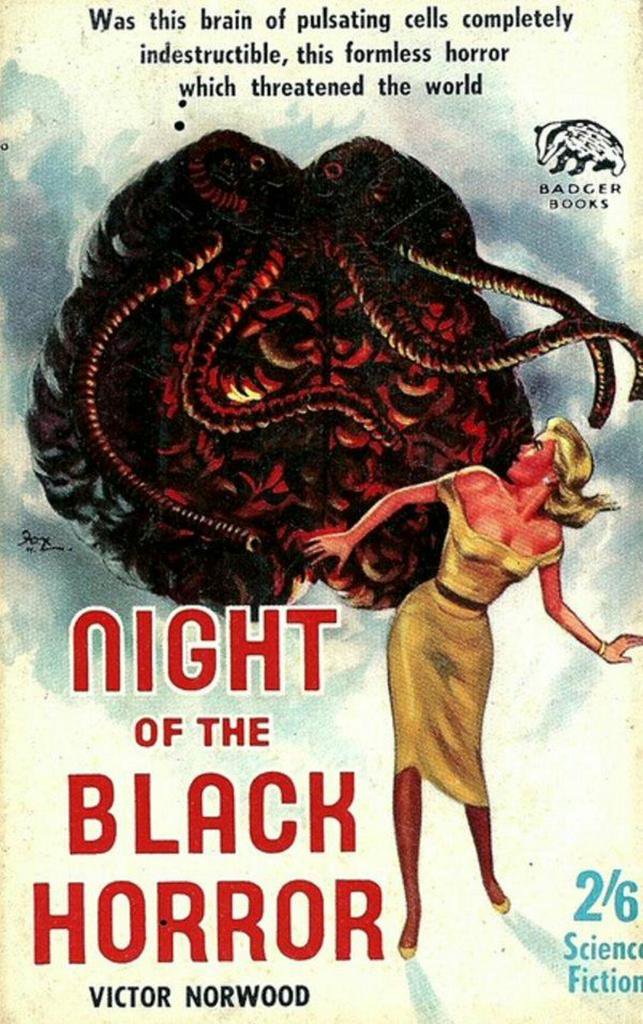

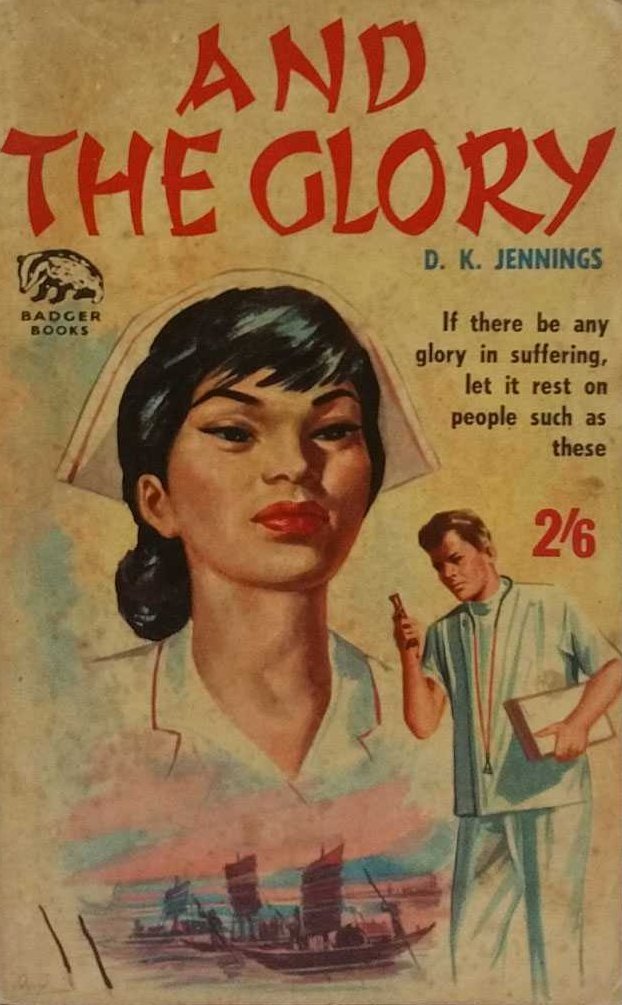

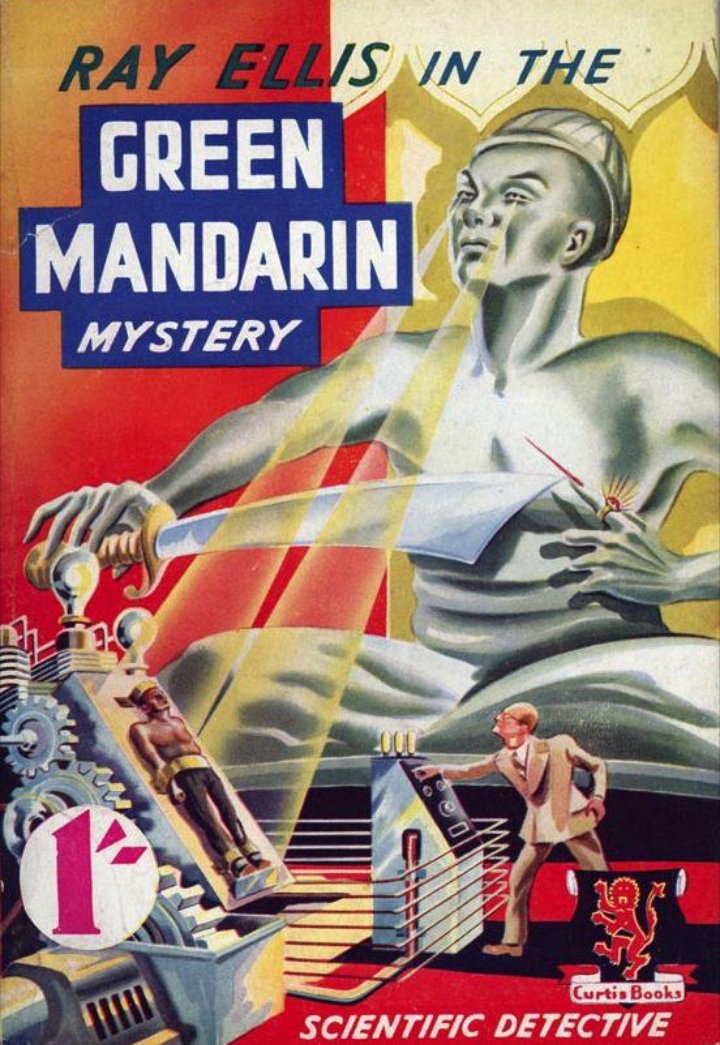

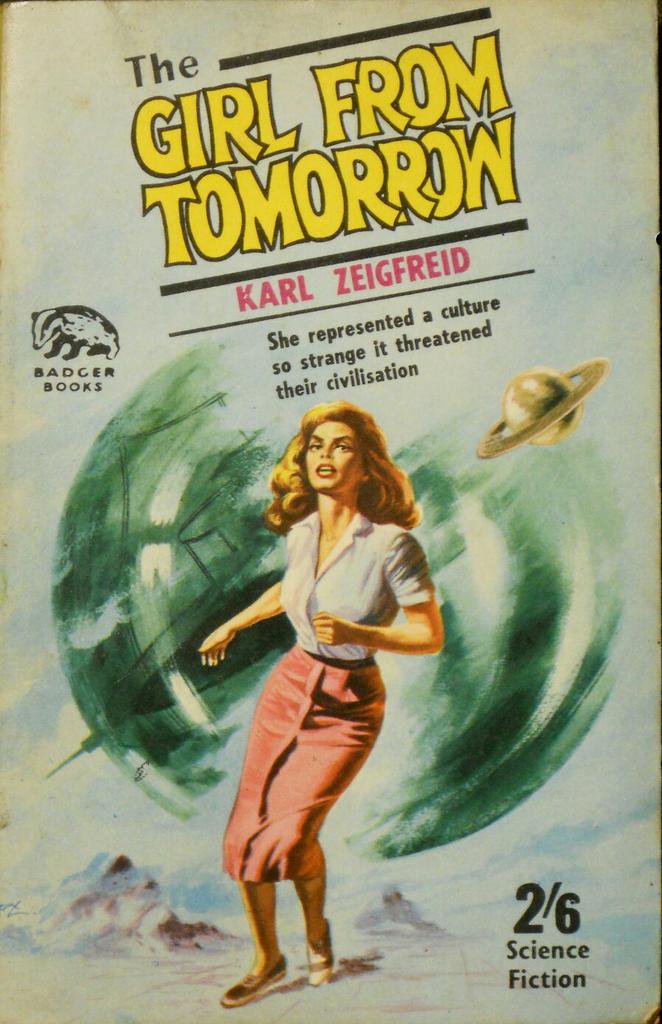

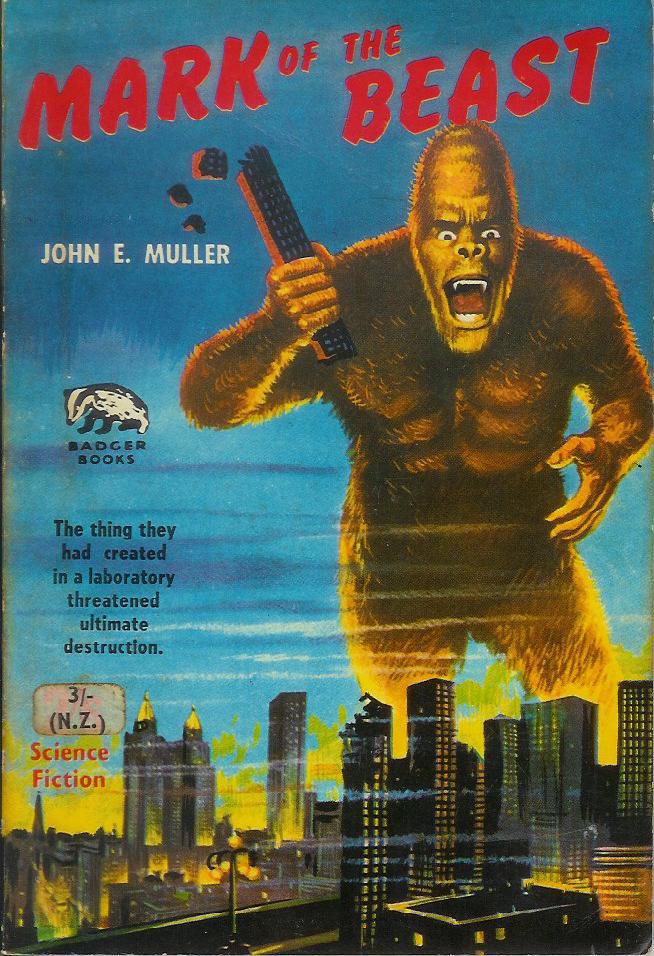

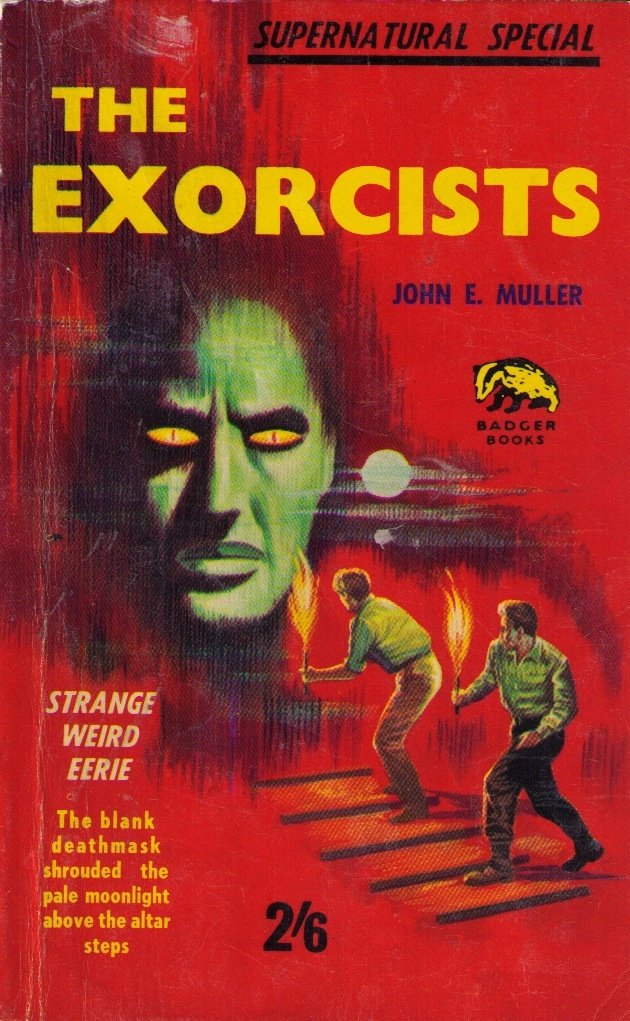

To mask their lack of authors Badger used a huge range of house aliases: Victor La Salle, John E Muller, Karl Zeigfreid, Chuck Adams, Tex Bradley, Trebor Thorpe, D.K. Jennings and Pel Torro were some of the many disguises that Fanthrope, Glasby and a few other writers hid behind.

Badger also had a unique method of commissioning work. A book cover – normally painted by Henry Fox – would be sent to Glasby or Fanthrope, who would then come up with a title and quick synopsis. They would then turn that into a 45,000 word story, normally within a week.

Fanthrope’s approach to writing was to cover himself with a blanket and then, armed with a thesaurus, dictate his story into a tape recorder. Family members would type these up as he continued dictating and when he was close to 45,000 words he would rapidly end the novel.

The result was a unique stream-of-consciousness repetitive prose style: “He was disarmed, demobilised, defenceless, powerless. His exhaustion was complete; he was in a state of utter fatigue, complete collapse, and total breakdown… He fainted; he swooned; he passed into a coma.”

Some of Fanthrope’s stories were barely-disguised retellings of Shakespearian plays or Greek myths set in space. Others were outrageous padded to reach the required word length; 10 pages describing the moves in a chess game, paragraphs of synonyms to describe a moment of silence.

Supernatural Stories was the only digest magazine Badger Books kept going, producing over 100 editions including novel-length Supernatural Specials. Fanthrope wrote the majority of these stories, as well as most of the science fiction Badger produced.

Glasby focussed more on the westerns and war stories, producing over 160 WW2 novels and an almost equal number of western adventures. He also write the short-lived range of spy and crime novels Badger introduced in 1966 as an attempt to cash in on the James Bond market

Many Badger books were translated into German, Italian and French and issued by other publishers to fill the needs of local markets. Vega Books – a US imprint owned by Les Aday that specialised in erotica – also published 14 Badger titles using Henry Fox’s cover art.

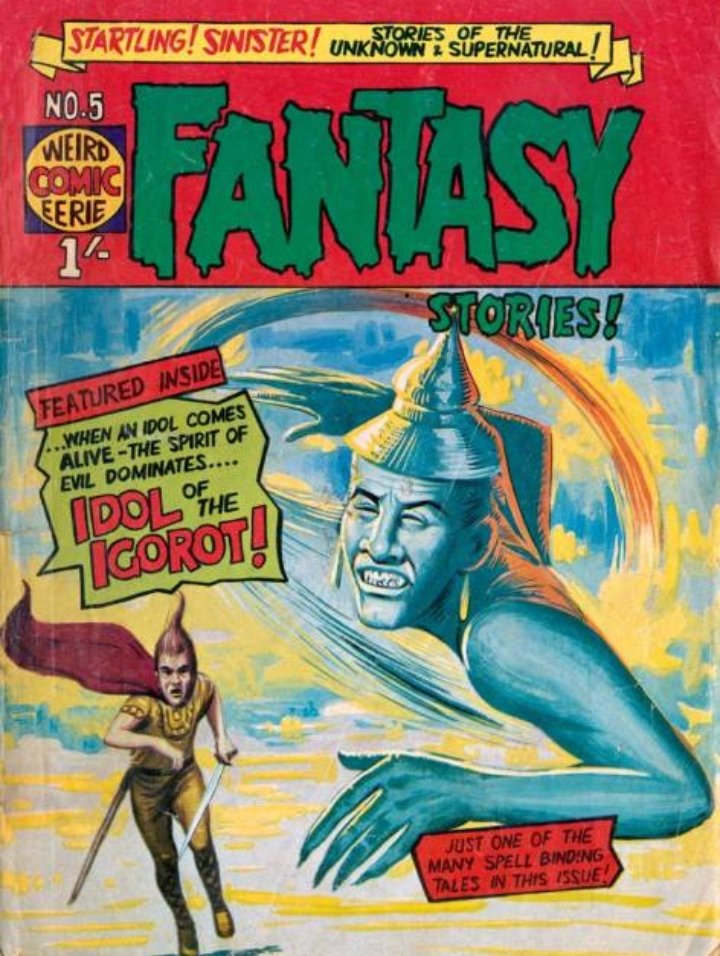

Badger Books was a formidable publishing machine, run on a shoestring but at its peak turning out a new book every week. However the boom couldn’t last, and by the mid-1960s sales began to decline. So in 1966 Spencer tried to diversify into comics.

Mick Angelo, former editor of Classics Illustrated, produced four titles for Spectre, mostly macabre horror tales similar to Fanthorpe’s Supernatural Stories. However sales were poor, as was the artwork and printing. Finally in 1967 Badger Books ceased publishing.

As for the writers John Glasby continued his career at ICI, eventually becoming head of Public Relations before retiring. The Reverend Lionel Fanthorpe became a head teacher, a weightlifting instructor and eventually a presenter on Fortean TV.

Badger Books didn’t last long and their books were hardly classics, but they embodied the three main features of pulp fiction: sensationalism, an idiosyncratic writing style, and great haste! Alas we shall never see their like again.

More stories another time…

More stories another time…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh