At #APSA2019, @szasulja and I are presenting our research on why online political discussions are perceived as more toxic than offline political discussions. We provide evidence against a common media narrative: The mismatch hypothesis. A thread on our key findings: (1/9)

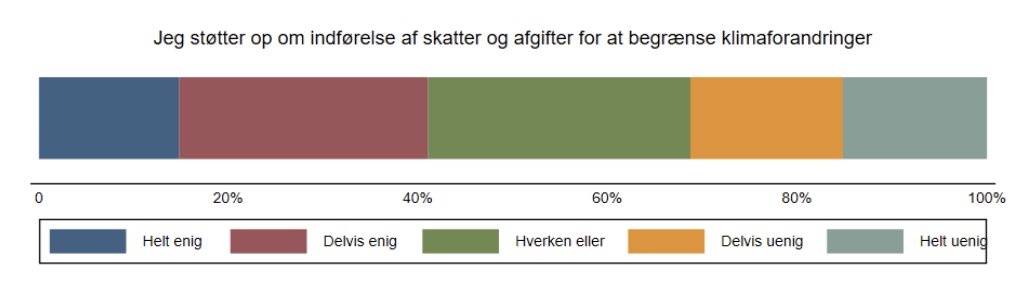

We use representative surveys from the US and Denmark to document that people at large do indeed perceive online environments as more hostile than offline. In figure, higher values equals more perceived hostility and dark gray plots show distribution for "online debates". (2/9)

The mismatch hypothesis says this reflects a mismatch between (a) a human psychology adapted for face-to-face interaction and (b) the impersonal online environment. We test three versions of the mismatch hypothesis: Mismatched-induced change, selection and perception (3/9)

CHANGE: Do online environments induce hostility because nice people are less able to regulate their emotions online? No. People who report that they are hostile online also report that they are hostile offline. There are no differences across the two context. (4/9)

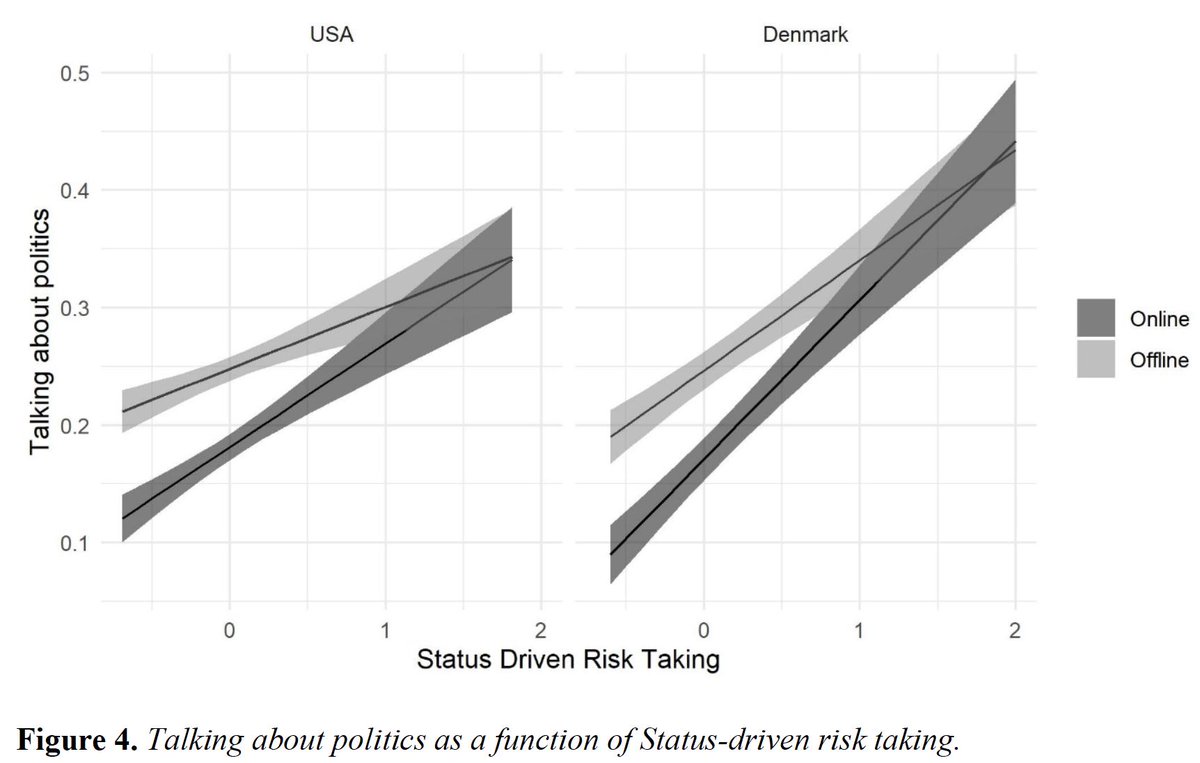

SELECTION: Are online environments hostile because the setting is attractive to those predisposed for hostility? No. Hostile people (e.g., status-obsessed individuals) talk about politics whenever they can. However, non-hostile individuals do opt out of online debates. (5/9)

PERCEPTION: Do people misinterpret benign intentions as hostile in online debates? No. When asked about own experiences, conflicts online and offline are perceived as equally severe. Using behavioural experiments, we also find no systematic bias in perceptions of SoMe posts (6/9)

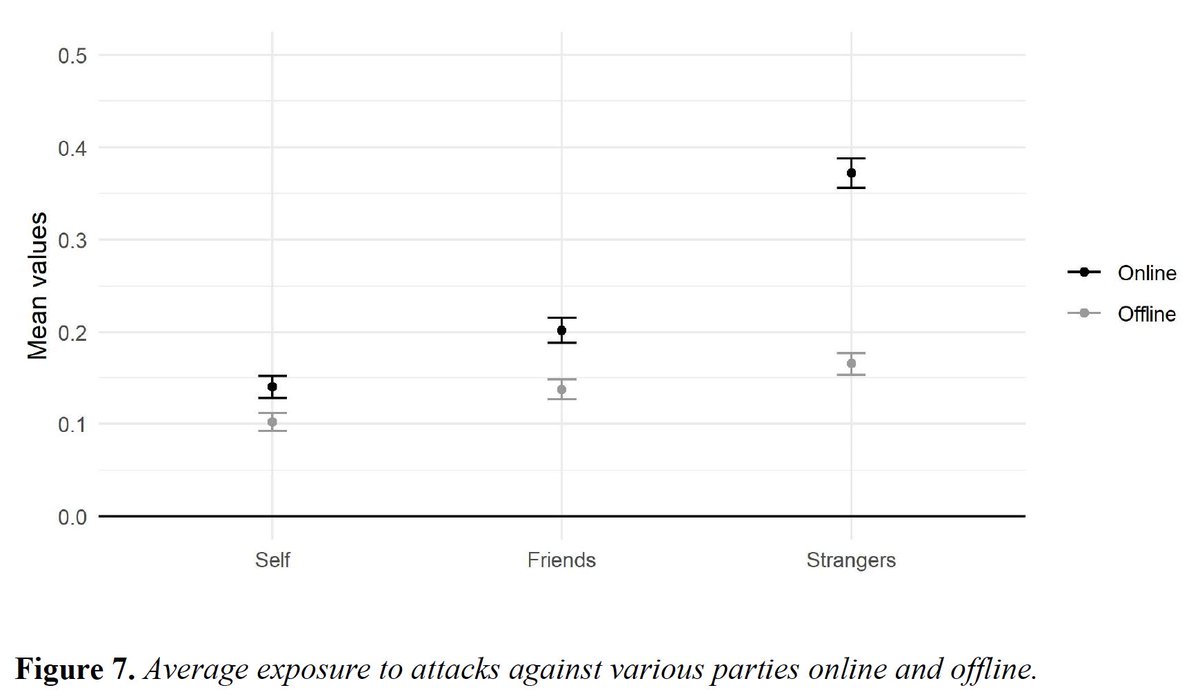

What then explains 'the hostility gap'? Rather than psychological mismatches, the gap seems to reflect that the public nature of online discussions exposes people to way more hostile attacks directed against strangers. Offline, these are hidden to the public eye (7/9)

How to guard against online hostility? Online hostility is not an 'accident' but a deliberate strategy pursued by predisposed people. While many might not fall victim to their attacks, these are nonetheless public, shaping overall perceptions. We need to contain such people (8/9)

To hear more come to this panel on Friday, where we and our co-presenters focus on bad stuff happening on the Internet: convention2.allacademic.com/one/apsa/apsa1… (9/9)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh