#EchoFirst #Cardiotwitter Our paper on normal global strains in three dimensions from the #HUNT study is out. openheart.bmj.com/content/6/2/e0…

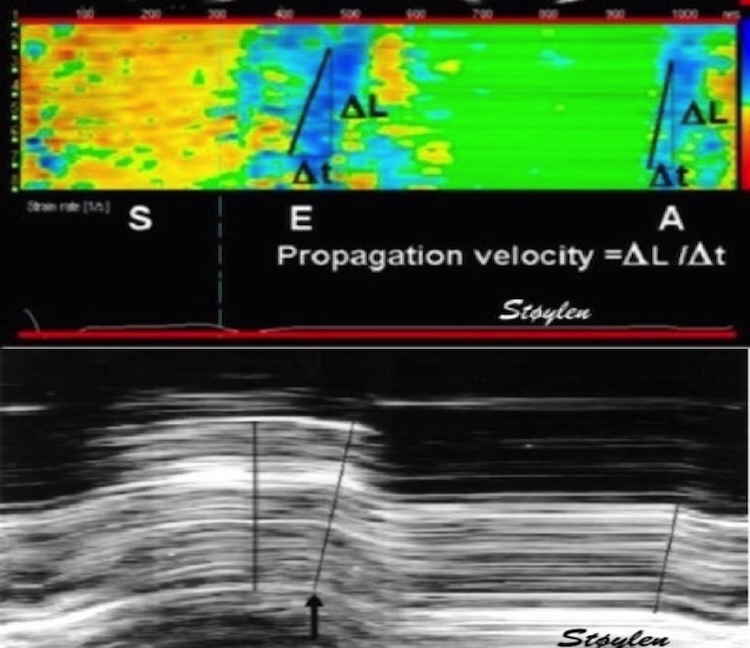

/1 Strain is relative deformation in three dimensions; simple linear measures of end diastolic and end systolic dimensions. Linear measures are vendor independent, with no need for advanced technology, but the measures are method dependent.

/2 Strain analysis of the LV myocardiumtreats the LV myocardium as ONE object deforming in three dimensions, longitudinal, transmural and circumferential.

The three normal LV strains; longitudinal, circumferential and transmural do not reflect directional fibre shortening, they are simply the three spatial coordinates of the total deformation of the three-dimensional object; the LV myocardium.

the xyz and longitudinal/transmural/circumferential coordinate systems are equivalent. Nobody would talk about three independent functions along the x/y/z axes, so why would it be along the l/t/c axes?

/3 The three strains are interrelated, indicating very little myocardial systolic compression. This means that the main information is carried by longitudinal strain. When an incompressible object deforms along ONE dimension, it has to deform along the other two as well.

When the LV shortens, it has to thicken. Wall thickening pushes both endocardial and midwall circumferences inwards so they shorten. Circumferential strain is the same as diameter shortening.

/4 There is a gradient of circumferential strain from outer to inner circumference. Outer circumferential shortening is the true circumferential fibre shortening, while the deeper circumferential strains are increasingly a function of wall thickening.

/5 All three strains are body size, gender and age dependent. Gender dependency is only due to body size. Both age and body size dependency is highest for longitudinal strain.

All there strains decline with age. Thus, there is no increase in short-axis (circumferential) function to compensate for the reduced longitudinal function, despite preserved EF by age.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh