Hello again! @iandavidmorris here.

Following yesterday’s thread, let’s talk about slave soldiery in Islam.

Enslaved people have been made to fight across many ancient and medieval societies, but they were nowhere so prominent as in the Islamic world.

Following yesterday’s thread, let’s talk about slave soldiery in Islam.

Enslaved people have been made to fight across many ancient and medieval societies, but they were nowhere so prominent as in the Islamic world.

https://twitter.com/Tweetistorian/status/1193852876071849987

@iandavidmorris It was illegal to enslave a Muslim. At the same time, slaves might convert to Islam, and there was a lot of social pressure to free Muslim slaves.

New slaves were therefore not born in Muslim lands, for the most part, but stolen from the frontiers.

New slaves were therefore not born in Muslim lands, for the most part, but stolen from the frontiers.

@iandavidmorris On the steppes of Central Asia, a nomadic lifestyle prevailed. Children were taught from a young age to ride and to fight on horseback.

When they were captured and sold into slavery, children and young adults already knew the fundamentals of steppe warfare.

When they were captured and sold into slavery, children and young adults already knew the fundamentals of steppe warfare.

@iandavidmorris Meanwhile, in the Muslim empire, the caliphs no longer felt that they could rely on the regular army.

The reasons for this are a bit complicated, but I’ll keep it brief:

The reasons for this are a bit complicated, but I’ll keep it brief:

@iandavidmorris The first great dynasty of Islam, the Umayyads, were based in Syria, and they employed Syrians to do most of their fighting.

But the Umayyads were overthrown by a popular revolution in 750. Most of the revolutionaries came from the east: Iraq and Iran.

But the Umayyads were overthrown by a popular revolution in 750. Most of the revolutionaries came from the east: Iraq and Iran.

@iandavidmorris The revolution had no single figurehead and no fixed demands. There were dozens of factions with conflicting plans to seize power.

All they agreed on was that the Umayyads had to go.

All they agreed on was that the Umayyads had to go.

@iandavidmorris So when the Abbasid faction won the throne, it had to purge all the other factions. The revolutionaries were killing their own.

@iandavidmorris And because the revolution had no unifying demands, the Abbasids had no real plan of action.

Their major selling point was that they weren’t the Umayyads; but all the social ills that plagued the Umayyads also plagued the Abbasids.

Their major selling point was that they weren’t the Umayyads; but all the social ills that plagued the Umayyads also plagued the Abbasids.

@iandavidmorris The revolution of 750 was violent, destabilising, and basically pointless.

So when it came to building a new army, the Abbasids had to ask themselves: does anyone really *want* to fight for us?

So when it came to building a new army, the Abbasids had to ask themselves: does anyone really *want* to fight for us?

@iandavidmorris After a series of nasty rebellions and civil wars, the Abbasid caliph al-Mu‘tasim tried a radical new strategy.

Not free Muslim volunteers, but slave soldiers, would form the backbone of his imperial army.

Not free Muslim volunteers, but slave soldiers, would form the backbone of his imperial army.

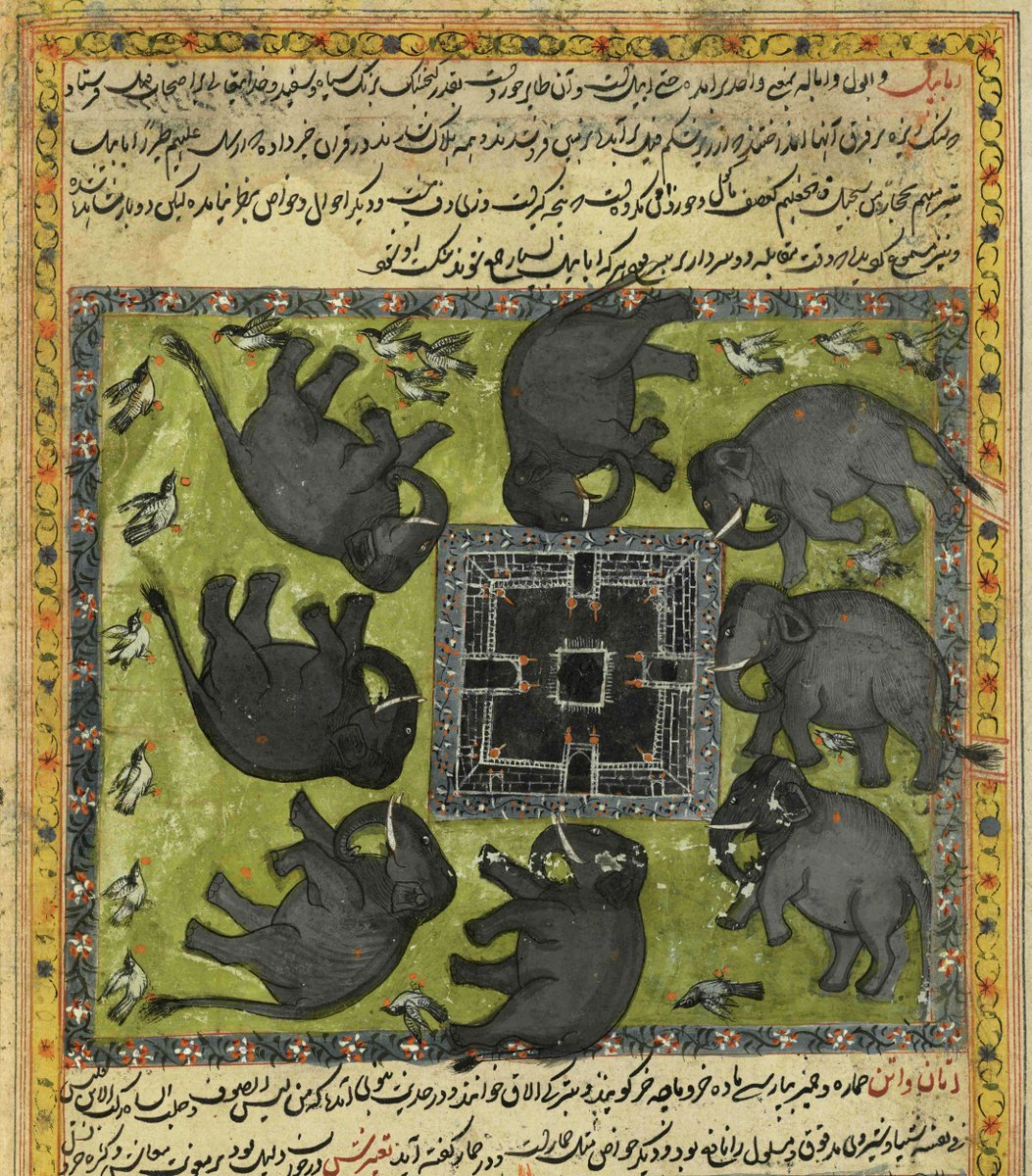

@iandavidmorris Al-Mu‘tasim and his successors, based in Iraq, imported thousands of boys from Central Asia.

They were converted, trained and educated in the palace complex. There was no meaningful contact with the outside.

The caliph was the centre of their world.

They were converted, trained and educated in the palace complex. There was no meaningful contact with the outside.

The caliph was the centre of their world.

@iandavidmorris Unlike paid soldiers, slave soldiers had no regional loyalties, no ideological conflicts—no ties outside the ruling house.

The Abbasids had solved their problem!

…Or so they thought.

The Abbasids had solved their problem!

…Or so they thought.

@iandavidmorris Trained and trusted, the slave soldiers were given key roles in the palace. They heard all the gossip, all the state secrets. They learned the dark arts of politics.

All this while they controlled who got in and out of the palace.

All this while they controlled who got in and out of the palace.

@iandavidmorris The caliphs thought the slave soldiers were their prisoners. That was a fatal mistake.

@iandavidmorris There will be more about the rise of the slave soldiers tomorrow: this thread is already too long, and I must sleep.

In the meantime, please send me comments, queries and criticisms!

—IDM

In the meantime, please send me comments, queries and criticisms!

—IDM

@iandavidmorris Part 3

https://twitter.com/Tweetistorian/status/1194700315444023297

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh