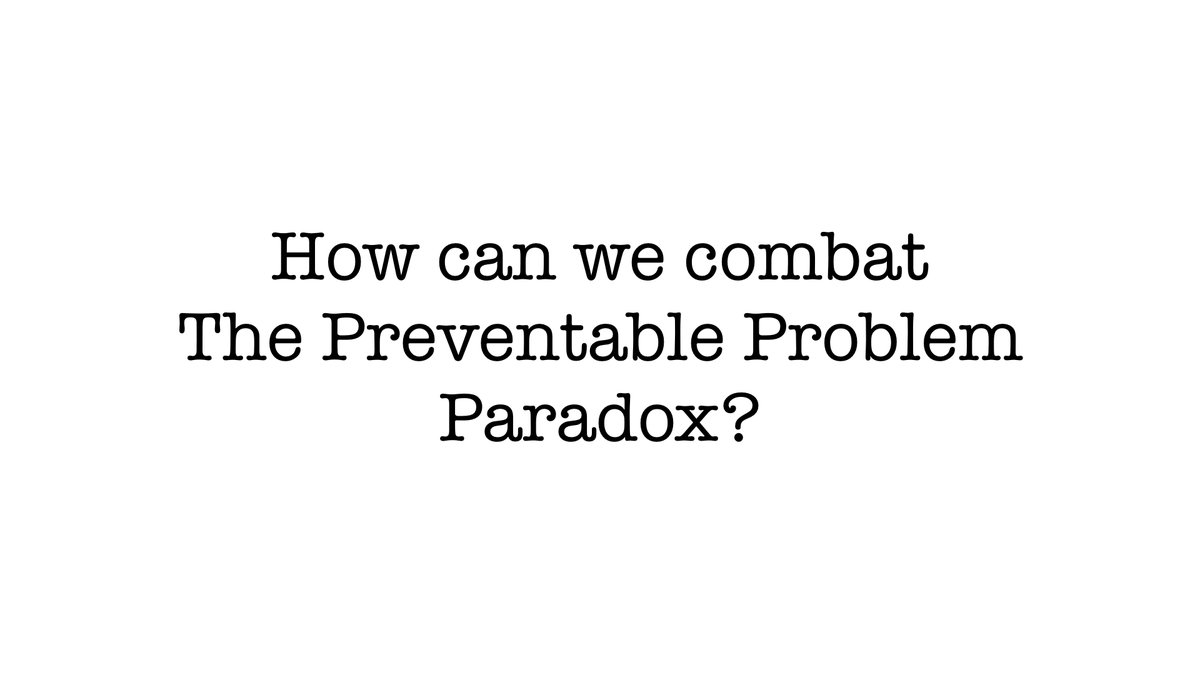

Why do smart companies & orgs make stupid mistakes?

A thread:

A thread:

Last month, I gave a talk about product management & leadership @SVPMA.

This Tweetstorm covers one of the seven topics I presented at the talk.

It’s the topic that appeared to resonate the most with the audience.

This Tweetstorm covers one of the seven topics I presented at the talk.

It’s the topic that appeared to resonate the most with the audience.

https://twitter.com/shreyas/status/1196807903929229313

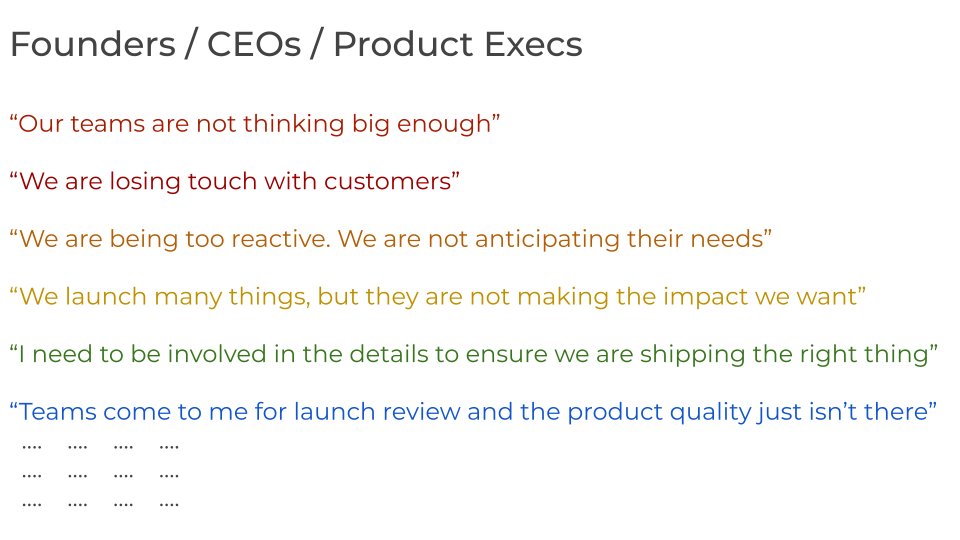

Why does Facebook make stupid mistakes, over and over and over again?

What about the mistakes that Uber, Google, and so many others in our industry have made over the years?

Mind you, I’m not talking about “mistakes in hindsight”.

Rather they are the “what the heck were these people thinking?” flavor of mistakes.

Rather they are the “what the heck were these people thinking?” flavor of mistakes.

When we read exposés in the press that lay out the timeline and events leading up to such mistakes (and there have been so many in just the past 5 years), the most common conclusion (incorrect) tends to be:

“The people in these companies are stupid”

“The people in these companies are stupid”

The next most common conclusion tends to be:

“The people in these companies are evil”

(also incorrect)

“The people in these companies are evil”

(also incorrect)

So, what is actually going on when an otherwise smart, well-meaning organization makes obvious blunders?

And why do some organizations tend to do this over and over again?

And why do some organizations tend to do this over and over again?

While the exact details surely vary across these situations, one organizational cognitive bias most often at the root.

What is it?

What is it?

Now, why do smart, even tremendously-successful organizations fall prey to this?

There’s no better way to understand that than watching this scene from Superman II.

It is, IMVHO, among the greatest 200 seconds in motion picture history.

It is, IMVHO, among the greatest 200 seconds in motion picture history.

Watch it. I’ll wait.

(For future readers: Use this link if the YT video gets taken down for some reason:

google.com/search?q=super… )

(For future readers: Use this link if the YT video gets taken down for some reason:

google.com/search?q=super… )

No, really, watch that scene before moving to the next Tweet.

Welcome back. So, what did we just see?

Let’s break it down.

Let’s break it down.

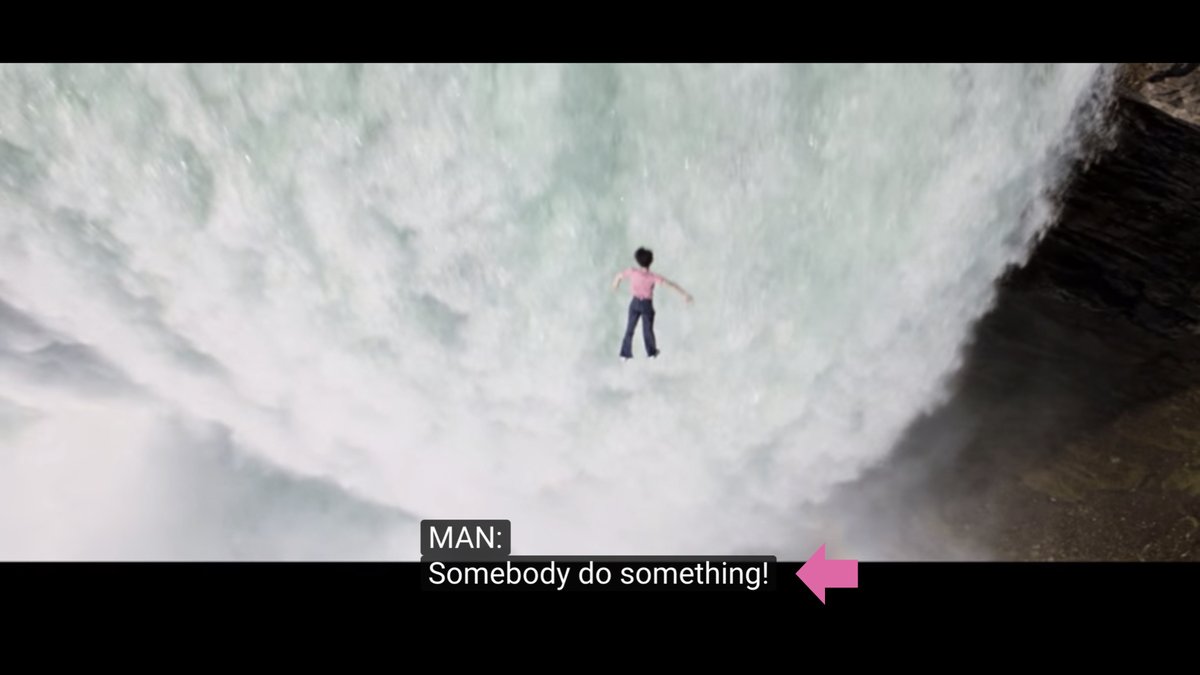

Clark Kent (who is actually Superman) at Niagara Falls with colleague (and love interest) Lois Lane.

Clark rushes towards the boy, asking him to stop. Boy’s mom also notices and manages to get the boy down. He's safe now.

Clark heads over to the nearby hot dog stand.

Boy is at it again, but this time, putting himself in even greater danger (he’s now on the other side of the railing).

Boy is at it again, but this time, putting himself in even greater danger (he’s now on the other side of the railing).

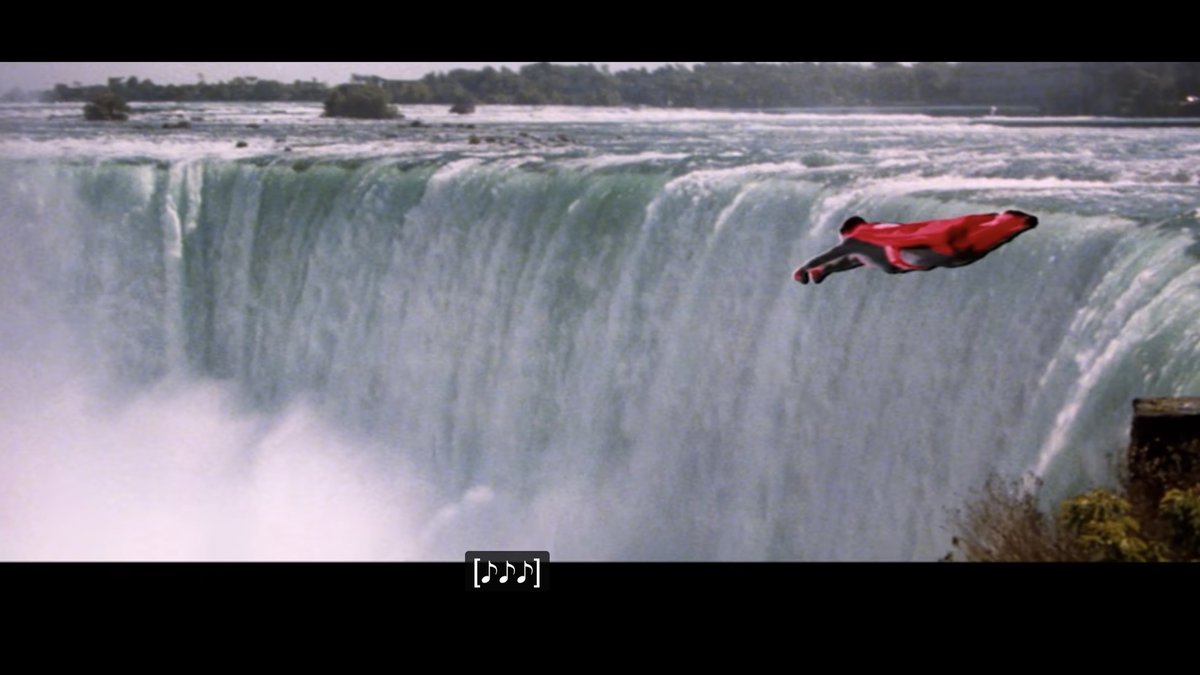

Look at Lois Lane. Pretty much ignored Clark Kent earlier when he tried to save the boy, but is vying for Superman’s attention after this dramatic save.

Now, I have a question for you.

If Superman is like most of us — if he cares about appreciation for a job well done — what will he do the next time he’s in this situation?

If Superman is like most of us — if he cares about appreciation for a job well done — what will he do the next time he’s in this situation?

(A) Will he try to prevent the boy from falling?

Or, (B) will he let the boy fall, transform into Superman within a nanosecond, and heroically rescue the boy from certain death?

Or, (B) will he let the boy fall, transform into Superman within a nanosecond, and heroically rescue the boy from certain death?

It should be obvious that, if he’s motivated by appreciation and accolades (as certainly most humans are), you should bet on (B), not (A), being the correct answer.

Mind you, this is not merely an academic question.

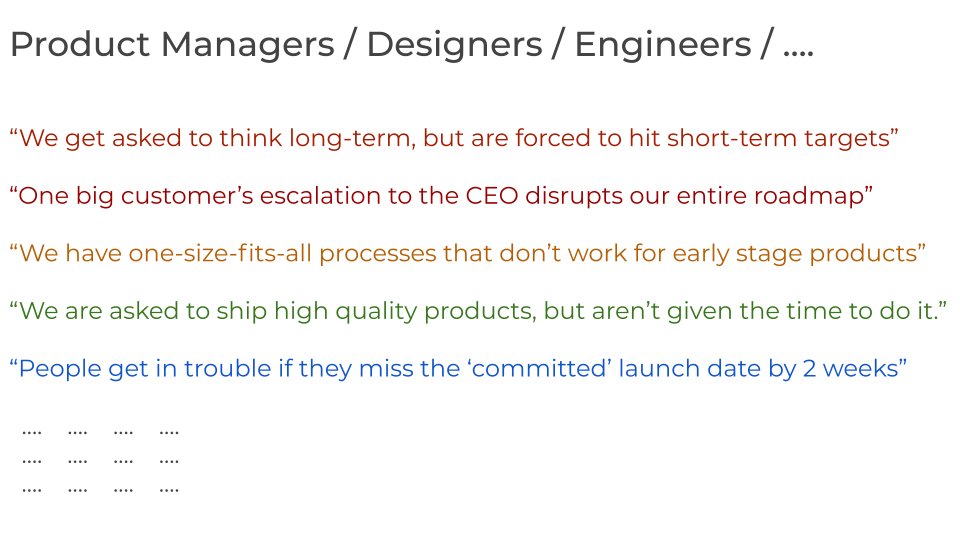

Because what you just saw happens in the organizations that we’re part of, every... single... day....

In fact, this is such a common phenomenon that once you understand it, you’ll see it everywhere. Companies, non-profits, government. Especially the government.

And while no organization (or leader) *wants to* incentivize problem creation over problem prevention, they unwittingly end up doing it anyway.

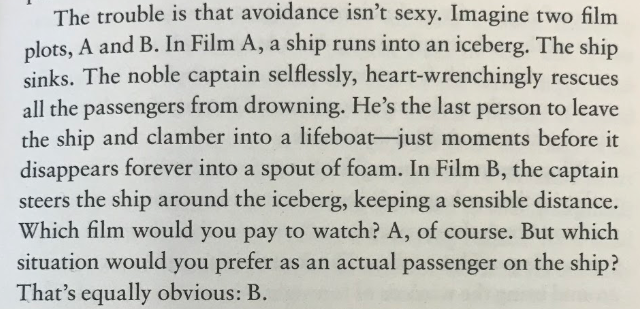

This paradox is so important for us to understand, as a community and as a society, that I’m going to share another story.

What you’re about to see is a remarkable couple of paragraphs from Rolf Dobelli’s excellent book “The Art of The Good Life”*

amazon.com/Art-Good-Life-…

* As an aside, this is one of my top 5 all-time favorite books.

amazon.com/Art-Good-Life-…

* As an aside, this is one of my top 5 all-time favorite books.

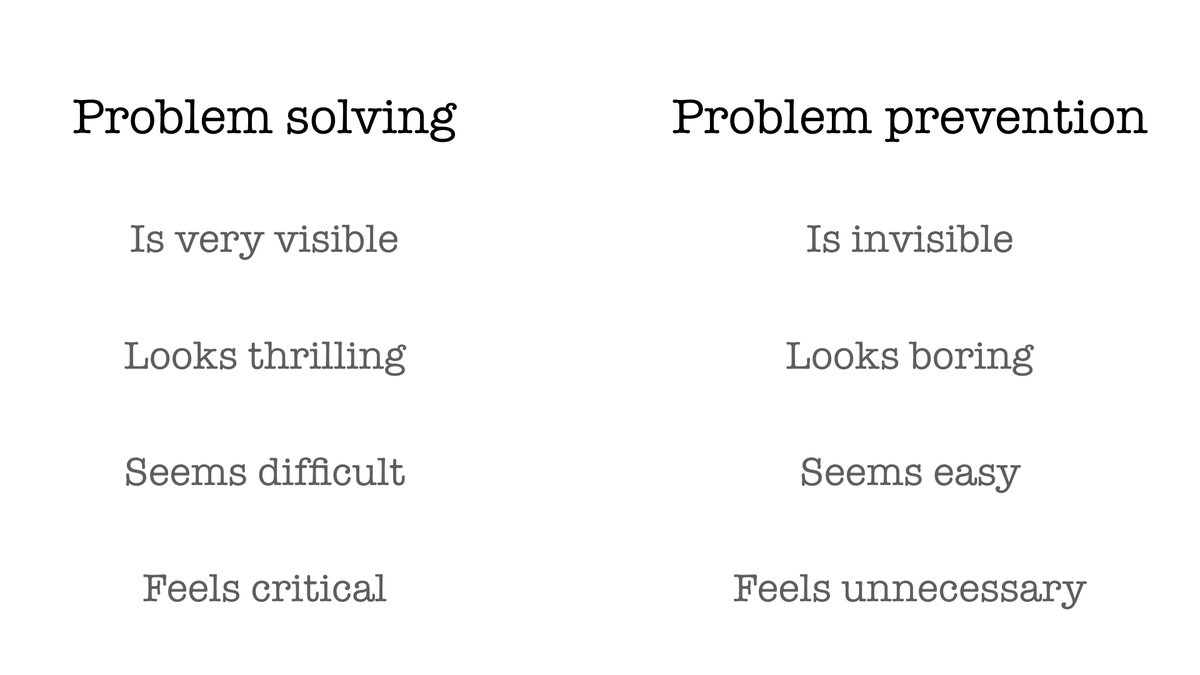

With this contrast between how humans innately perceive problem solving vs. problem prevention, is it any surprise that this paradox permeates almost every complex organization?

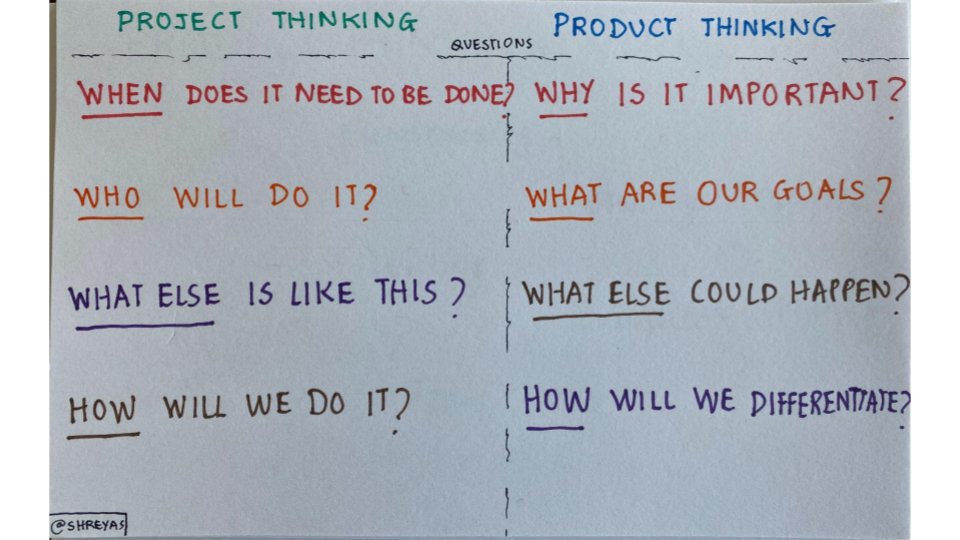

Let’s bring this back to product management (and leadership in general).

In the earlier stages of your career as a PM (or a leader), it makes sense for you to go in and solve whatever problem is facing the team.

And some PMs (and leaders), after multiple years of doing this, convince themselves that problem *solving* is their job. They come in to the office, look for the “problem of the day”, and then get to work.

However, if you want to be a true and unselfish leader of people,

to do what’s right for your company,

you need to be the captain who just avoids the iceberg,

and not the one who hits it and then heroically attempts to rescue everyone.

to do what’s right for your company,

you need to be the captain who just avoids the iceberg,

and not the one who hits it and then heroically attempts to rescue everyone.

Leaders looking to combat the preventable problem paradox within their organization should:

1. Create awareness of its existence

2. Change the mechanisms for rewards and recognition

3. Embrace pre-mortems

1. Create awareness of its existence

2. Change the mechanisms for rewards and recognition

3. Embrace pre-mortems

Want to learn more about these solutions?

Share the excitement via your replies, quote Tweets, retweets, and faves, and I’ll post a follow up thread within the next few days.

(warning: it’ll be equally long :) )

To be continued...

Share the excitement via your replies, quote Tweets, retweets, and faves, and I’ll post a follow up thread within the next few days.

(warning: it’ll be equally long :) )

To be continued...

If you reached this far (❤️), check out my talk about PM leadership from 2018 (along with another long Tweetstorm):

https://twitter.com/shreyas/status/1058908181630398464

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh