Apparently some are still under the impression that the Birmingham Fragment (Mingana 1572a + Arabe 328c) is pre-Uthmanic copy of the Quran. This is impossible, despite its strikingly early C14 dating (568-645 CE with 95.4%) it is clearly a descendant of the Uthmanic text type.

In "The Grace of God" I develop a method to show that all early manuscripts descend from a single copy of the Quran. This single copy is what we call the Uthmanic Archetype (as most likely the caliph Uthman was the one who commissioned it).

Open Access: doi.org/10.1017/S00419…

Open Access: doi.org/10.1017/S00419…

So how does this method work? Throughout the Quran, there are words that are spelled in two different ways, without any impact on the meaning. We must conclude that these spellings were up to the scribe For example niʿmat aḷḷāh "the grace of God" is spelled in two ways.

If in such idiosyncratic spellings we find time and time again that different manuscripts have the same spelling in the same place in the Quran, they must have a common ancestor.

I used niʿmat aḷḷāh for this as it occurs almost 50/50 in both spellings.

I used niʿmat aḷḷāh for this as it occurs almost 50/50 in both spellings.

It is as if you have 10 transcripts and you want to see if they were transcribed individually or copy-pasted 10x. If in it 50 times the word "the" occurs, and 25 times it is written as "teh" and all 10 transcripts have that in the exact same places it must have been copy-pasted.

Now the Birmingham fragment is too fragmentary to use niʿmat aḷḷāh as the only idiosyncrasy to prove its belonging to the Uthmanic text type, but there are many other idiosyncrasies that can be used just as well (I suggest a few in my paper). So let's do that!

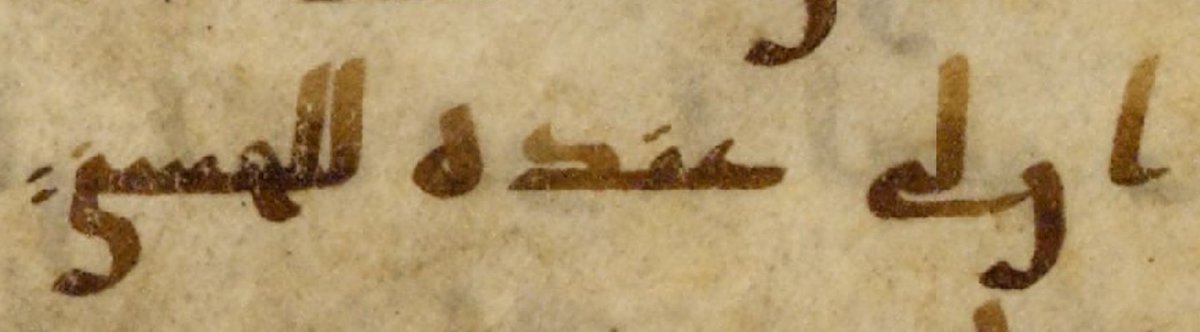

Q11:18 laʿnat aḷḷāh "the curse of God" is written with as لعنه الله, but could have been written لعنت الله too, as it is in Q3:61 and Q24:7.

As لعنه الله it is written in Q2:83, 161; Q3:87; Q7:44.

As لعنه الله it is written in Q2:83, 161; Q3:87; Q7:44.

Q11:27 al-malaʾu "the elders" could be written either الملا (Q7:60, 66, 75, 88, 90, 109, 127; Q12:43; Q23:33; Q28:38; Q38:6) or الملوا (Q23:24; Q27: 29, 32, 38),

Q11:71 min warāʾi "from behind ..." could have been written either من ورا (Q33:53; Q49:4; Q59:14) or من وراى (Q42:51).

Q11:87 našāʾu could have been written either نشا or نشوا. This spelling is unique to this verse in all manuscripts. The other spelling occurs 18 times. This one occurring in this exact place is a clear smoking gun of it being Uthmanic. cf. Q21:9, Q22:5 with the regular spelling.

Q20:12 ṭuwan (before correction) is spelled طاوى. This is a highly idiosyncratic spelling that is almost certainly archetypal. We find it everywhere in early manuscripts.

See Yasin Dutton's excellent article on this variant.

brill.com/view/journals/…

See Yasin Dutton's excellent article on this variant.

brill.com/view/journals/…

Q21:37 sa-ʾurī-kum is uniquely spelled with a wāw for a short u (only other words that do that are based on the plural marker ʾul-). This is a typical idiosyncratic spelling of the Uthmanic text type.

Q22:4 tawallā-hu uniquely breaks with the Quranic orthography to write ḏawāt al-yāʾ verbs before clitics with a yāʾتوليه is expected, but manuscripts all agree on this spelling (much to my chagrin as it a counterexample against my theory of the ē in Quranic Arabic).

Remember how I said Q23:24 is typical for spelling al-malaʾu with wāw ʾalif? There it is.

So that's all the ones I was able to find with a quick search. I bet there are even more, but even with this list the conclusion is undeniable: The Birmingham fragment is Uthmanic.

So that's all the ones I was able to find with a quick search. I bet there are even more, but even with this list the conclusion is undeniable: The Birmingham fragment is Uthmanic.

So how do we reconcile that with the early dating? There are only two options:

1. Uthman didn't standardize the text, but it was someone earlier than him, and that's why pre-Uthmanic texts share an archetype with post-Uthmanic ones.

2. The carbon dating is wrong.

1. Uthman didn't standardize the text, but it was someone earlier than him, and that's why pre-Uthmanic texts share an archetype with post-Uthmanic ones.

2. The carbon dating is wrong.

1. is perhaps attractive if you want to be revisionist, but probably needs more supporting evidence. Palaeography does not speak in favour of this conclusion; and you'd have to account for a whole bunch of other things that make it attractive to see Uthman as the standardizer.

2. There are good reasons to be skeptical of the Carbon dating. Alba Fedeli herself, who brought this manuscript to the spotlight is not inclined to see the manuscript as somehow pre-Uthmanic.

https://twitter.com/therealsidky/status/1220779146382598144

Sidenote: ʾibrāhīm is never spelled ابرهم in the sections retained, as is to be expected for an Uthmanic text. One would not predict the same outcome with a pre-Uthmanic text. See my new article on this discussion: doi.org/10.1017/S13561…

I hope this gives some insight into why we can say with great certainty that a manuscript is of the Uthmanic text type. Spellings are both idiosyncratic and extremely well-preserved, so we receive a direct signal from the spelling of the archetype by looking at manuscripts.

It is labour intensive work to do it in this kind of detail, but you quickly develop an eye for it. I hadn't done this explicitly before with this manuscript but I *knew* it was of the Uthmanic text type, and once I looked specifically, it turned out that intuition was right.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh