Historical Linguist; Working on Quranic Arabic and the linguistic history of Arabic and Tamazight. Game designer @team18k

26 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

First, it is important to note that there are functionally, and syntactically quite different uses of la-.

First, it is important to note that there are functionally, and syntactically quite different uses of la-.

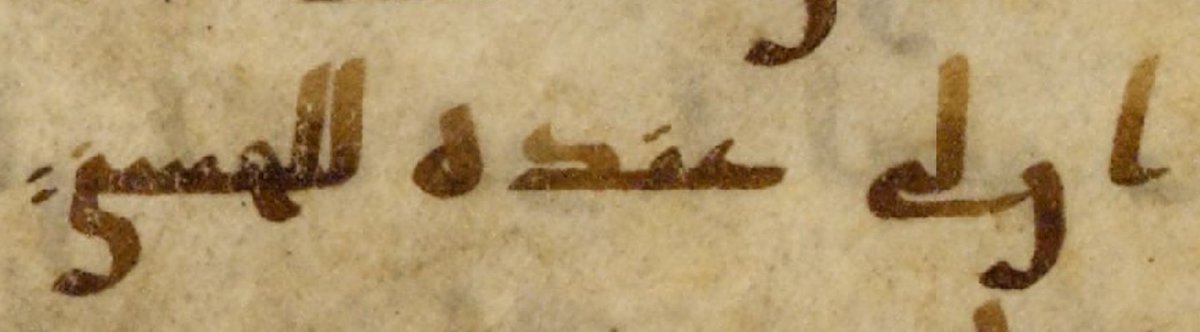

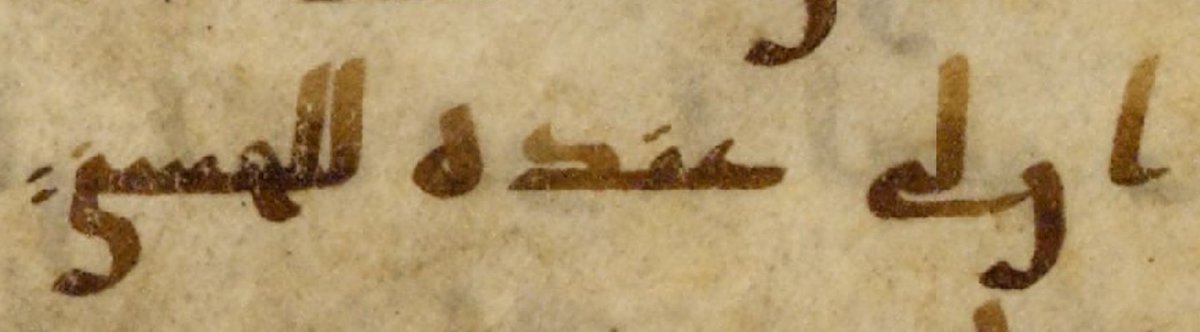

This is what Sibṭ al-Ḫayyāṭ says:

This is what Sibṭ al-Ḫayyāṭ says:

al-Dānī says: "Ibn Ḏakwān in my recitation to al-Fārisī from al-Naqqās (sic, Naqqāš) from al-ʾAḫfaš from him: wa-inna lyāsa with removal of the hamzah, and the rest read it with the hamzah (i.e. ʾilyāsa).

al-Dānī says: "Ibn Ḏakwān in my recitation to al-Fārisī from al-Naqqās (sic, Naqqāš) from al-ʾAḫfaš from him: wa-inna lyāsa with removal of the hamzah, and the rest read it with the hamzah (i.e. ʾilyāsa).

al-Dānī starts: "Nāfiʿ and the transmission of Hišām [from Ibn ʿĀmir] in my recitation [to my teachers] read "bi-ḫāliṣati ḏikrā d-dār" (Q38:46) without tanwīn as a construct phrase; the rest read "bi-ḫāliṣatin" with Tanwīn."

al-Dānī starts: "Nāfiʿ and the transmission of Hišām [from Ibn ʿĀmir] in my recitation [to my teachers] read "bi-ḫāliṣati ḏikrā d-dār" (Q38:46) without tanwīn as a construct phrase; the rest read "bi-ḫāliṣatin" with Tanwīn."

When a manuscript has an unknown non-canonical reading, it is typically unique to that manuscript: not a single manuscript is exactly alike. Nevertheless, we do find real 'patterns' among groups of manuscripts, that do things in similar ways that are distinct from known readings.

When a manuscript has an unknown non-canonical reading, it is typically unique to that manuscript: not a single manuscript is exactly alike. Nevertheless, we do find real 'patterns' among groups of manuscripts, that do things in similar ways that are distinct from known readings.

In the Quran today the Ark of the Covenant is spelled التابوت and pronounced al-tābūt. This is a loanword from the Aramaic tēḇōṯ-ā, likely via Gəʿəz tābōt.

In the Quran today the Ark of the Covenant is spelled التابوت and pronounced al-tābūt. This is a loanword from the Aramaic tēḇōṯ-ā, likely via Gəʿəz tābōt.

Turns out there is a beautiful perfectly regular distribution!

Turns out there is a beautiful perfectly regular distribution!

On the two page spread in the previous post alone there are 25 (if I didn't miss any) words that are not spelled the way we would "expect" them to.

On the two page spread in the previous post alone there are 25 (if I didn't miss any) words that are not spelled the way we would "expect" them to.

0:14 "what you see is 100% identical today to any Muṣḥaf".

0:14 "what you see is 100% identical today to any Muṣḥaf".

@BountyHunter255 1. Ḥimà-Sud PalAr8

@BountyHunter255 1. Ḥimà-Sud PalAr8

On page 25, Nasser tries to present an evolutionary model, with natural selection, by which some transmission paths of the seven readers become 'canonical', while others don't. One of these is that one "drops out" when diverging from the standard reading of the group...

On page 25, Nasser tries to present an evolutionary model, with natural selection, by which some transmission paths of the seven readers become 'canonical', while others don't. One of these is that one "drops out" when diverging from the standard reading of the group...

Ibn Ḫālawayh was Ibn Muǧāhid's student, who is widely held to be the canonizer of the seven reading traditions. Ibn Muǧāhid's book is the earliest book on the 7 reading traditions. But canon or not, Ibn Ḫālawayh's book actually describes 8 (adding Yaʿqūb).

Ibn Ḫālawayh was Ibn Muǧāhid's student, who is widely held to be the canonizer of the seven reading traditions. Ibn Muǧāhid's book is the earliest book on the 7 reading traditions. But canon or not, Ibn Ḫālawayh's book actually describes 8 (adding Yaʿqūb).

In this paper we try to describe the pronominal system used in early Islamic Classical Arabic. There is a striking amount of variation in this period, most of which does not survive into "standard classical Arabic".

In this paper we try to describe the pronominal system used in early Islamic Classical Arabic. There is a striking amount of variation in this period, most of which does not survive into "standard classical Arabic".

https://twitter.com/Quranic_Islam/status/1781866855990235365I think this is possible to some extent, yes. And so far this has really not been done at all. Most of the time people assume complete linguistic uniformity in the poetry, and don't really explore it further.

Traditionally, the third caliph ʿUṯmān is believed to have standardized the text.

Traditionally, the third caliph ʿUṯmān is believed to have standardized the text.

This feature was explained al-Farrāʾ in a lengthy discussion at the start of his Maʿānī. This makes sense: al-Farrāʾ was al-Kisāʾī's student who in turn was Ḥamzah's. Surprisingly in "The Iconic Sībawayh" Brustad is under the misapprehension that this is not a canonical variant.

This feature was explained al-Farrāʾ in a lengthy discussion at the start of his Maʿānī. This makes sense: al-Farrāʾ was al-Kisāʾī's student who in turn was Ḥamzah's. Surprisingly in "The Iconic Sībawayh" Brustad is under the misapprehension that this is not a canonical variant.

In Modern Standard Arabic, luġah basically just means "language", as can be seen, e.g. on the Arabic Wikipedia page on the Dutch Language which calls it al-luġah al-hūlandiyyah.

In Modern Standard Arabic, luġah basically just means "language", as can be seen, e.g. on the Arabic Wikipedia page on the Dutch Language which calls it al-luġah al-hūlandiyyah.

https://twitter.com/ArumNatzorkhang/status/1748744335036924119Let's first start with the rules:

Huehnergard (2007) quoted above seems to be aware of cases like laʿnat- pl. laʿanāt but claims that they are "occasionally found and not mandatory". But this is, really not correct, certainly not for the feminine nouns, where if you add -āt the -a- insertion is mandatory.

Huehnergard (2007) quoted above seems to be aware of cases like laʿnat- pl. laʿanāt but claims that they are "occasionally found and not mandatory". But this is, really not correct, certainly not for the feminine nouns, where if you add -āt the -a- insertion is mandatory.

Maḥmad would be a perfect match for the word-form found in the song of songs. But to give into that would of course be to allow for the Quran what they so readily consider acceptable for Hebrew, and are not willing to grant that. Double standards, plain and simple.

Maḥmad would be a perfect match for the word-form found in the song of songs. But to give into that would of course be to allow for the Quran what they so readily consider acceptable for Hebrew, and are not willing to grant that. Double standards, plain and simple.