(thread)

80s! Thinking about INPUT Magazine and the ill-fated Cliffhanger game they published as a type-in assembly code listing.

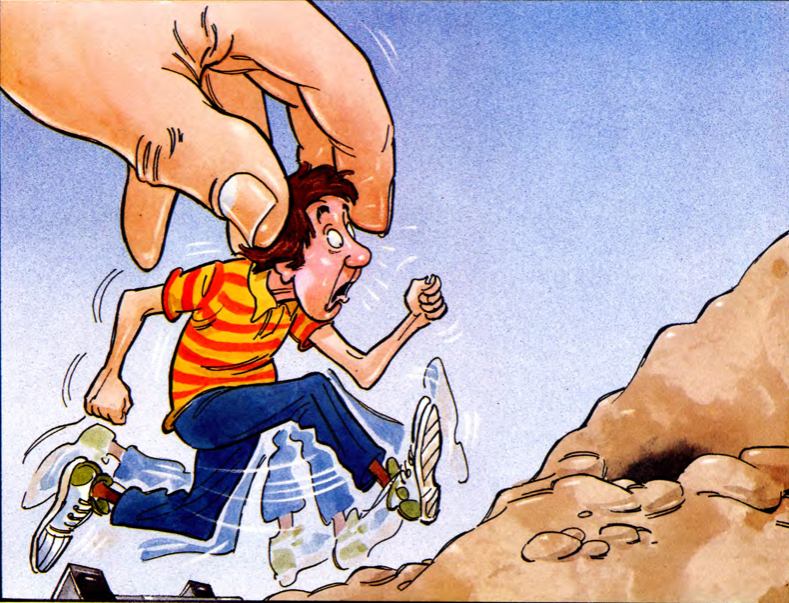

Although I never tried typing it in, the series of articles and their illustrations really fired up my imagination and got me excited about assembly

80s! Thinking about INPUT Magazine and the ill-fated Cliffhanger game they published as a type-in assembly code listing.

Although I never tried typing it in, the series of articles and their illustrations really fired up my imagination and got me excited about assembly

I was a BBC Micro owner. Here's a tiny snippet of the reams of code you'd be given to type in on the beeb.

I loved the illustrations! Different artists and photographers would be commissioned on various months publications.

Sadly, the entire thing was fatally flawed. That was the early 1980s, the days of desktop publishing - so staff had to enter code listings into DTP software by hand. LOTS OF TYPOS!

So until 2010, almost 30 years after publication, almost no-one had seen Cliffhanger running.

So until 2010, almost 30 years after publication, almost no-one had seen Cliffhanger running.

Marshall Cavendish, the publisher on INPUT, realised as they went along that they had lots of typos creeping into the listings published. So at the end the published a massive list of the assembler compiled bytes in memory for you to verify against memory!

Sadly, the listing of bytes in memory had exactly the same issue as the original assembly code: typos made by staff made while entering the masses of hex numbers.

So any attempt to enter the listing was doomed to failure.

The Cliffhanger articles spanned 150 pages of INPUT magazine (admittedly, with code for several different home computers).

I am so glad I never tried to type that in.

The Cliffhanger articles spanned 150 pages of INPUT magazine (admittedly, with code for several different home computers).

I am so glad I never tried to type that in.

Forward the clock almost 30 years. A hero, who I can't find the full name of -- Dave -- resurrected a working copy of Cliffhanger for the BBC Micro through excruciating means and wrote up the efforts and the history.

acornelectron.co.uk/eug/70/a-clif.…

acornelectron.co.uk/eug/70/a-clif.…

And the game isn't even very good. Very limited gameplay, poor graphics and animation (even by 80s standards).

There's a video of it for the BBC Micro:

There's a video of it for the BBC Micro:

In fact, this game could have probably been written in BBC BASIC and not much different. And then a reader might have successfully typed it in!

/end

#BBCMicro #retro #assembler #assembly #6502 #dtpDisaster #inputmagazine

/end

#BBCMicro #retro #assembler #assembly #6502 #dtpDisaster #inputmagazine

Oh, and if you want to see the Cliffhanger articles in their entirety, I've compiled into a single PDF here:

dropbox.com/s/g30l5hp4yi56…

dropbox.com/s/g30l5hp4yi56…

(Sorry, that Dropbox link no longer works, will resurrect it and update)

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh