The Italian city that beat the plague: Ferrara. Not a single plague death since 1576. How did they do it, and what lessons can we learn today? (TLDR the thread: early preventive action, vigilance, public funding, effective borders).

Funded in 400 A.D. as a Roman garrison, and annexed by the Papal State in 1598. In 1630 it had a pop. of 32k on 4.13km² (higher density than any mainland Chinese city), it had paved streets 1375, sewers since 1425. The 21st univ., funded in 1391 attracted Paracelsus, Copernicus.

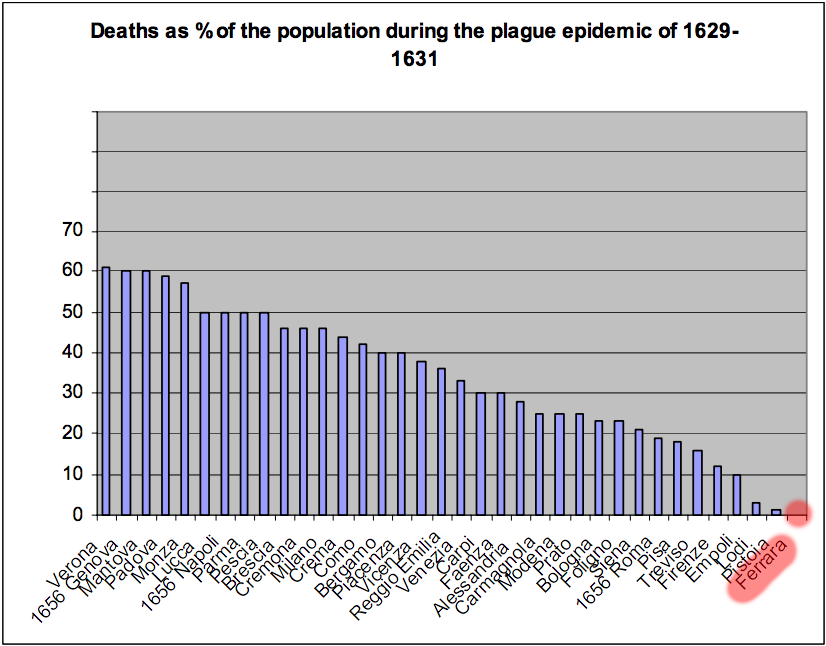

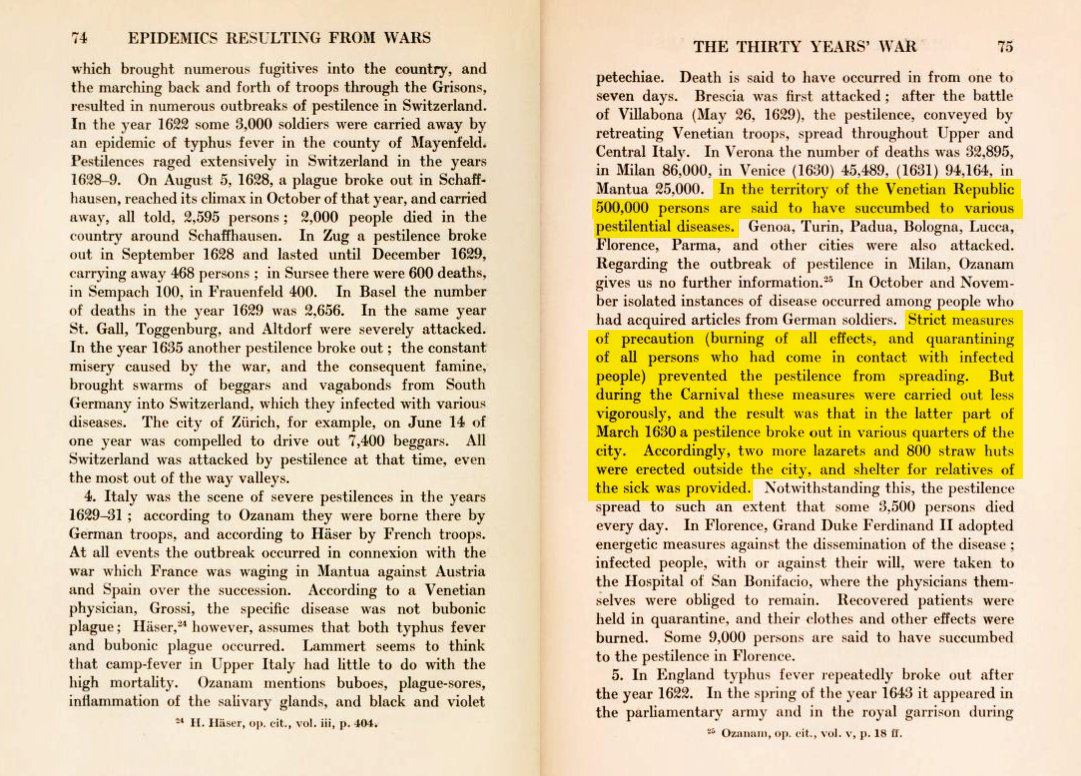

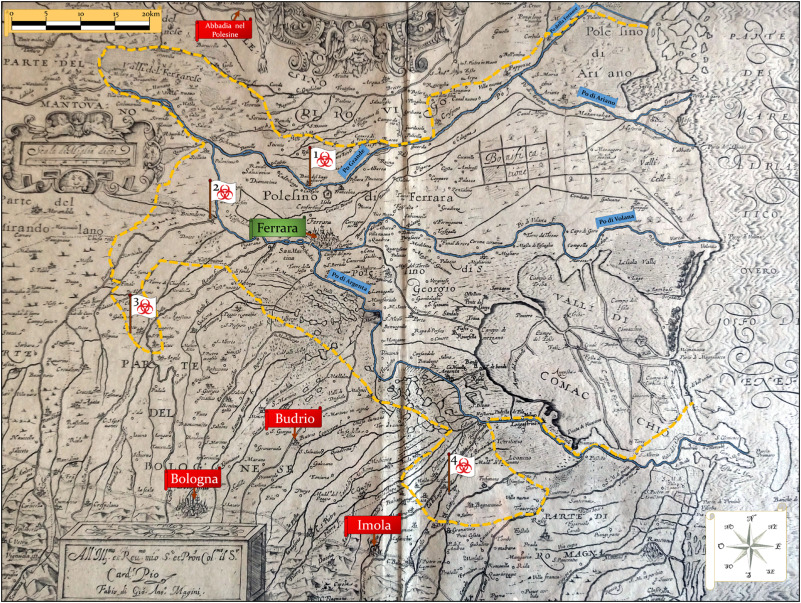

During the Italian plague of 1629-1631 it had zero deaths while northern Italy saw massive outbreaks during the War of the Mantuan Succession (Verona lost 61%!). The father of medical statistics, Friedrich Prinzing (1859-1938) described the toll the plague took on the region:

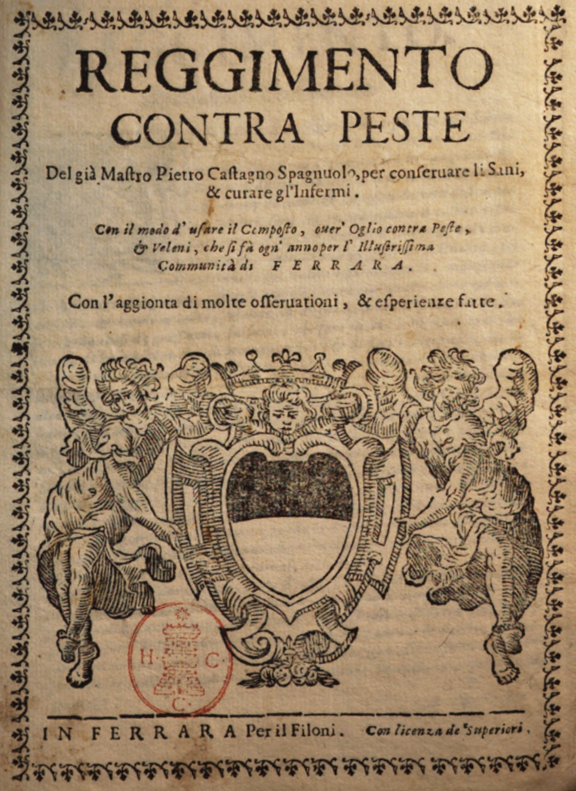

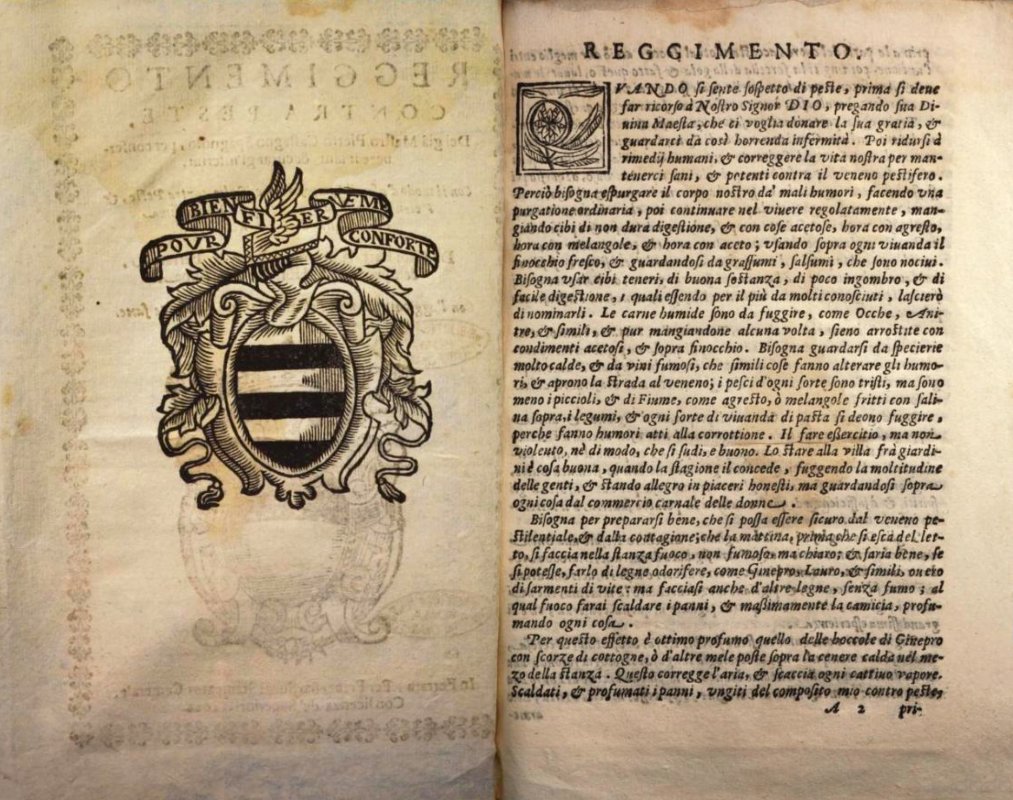

The story starts in 1528 after plague killed 20.2k in the city. The Duke summoned a Spanish physician Pedro (or Pietro) Castagno, a renowned international expert on plague control. He wrote down the city disease rules in the book "Reggimento contra peste", which became law.

The city had a permanent health authority, "Congregazione della Sanità", consisting of the Papal legate, noblemen, physicians, the apothecary of city hospital and eight gentlemen ”Gentiluomini” born in Ferrara, and an expert in foreign countries, borders, plague and trade.

Borders were controlled by checkpoints, and there were in times of plague were reinforced by teams of public health officials, "Signori Conservatori". Any traveler had to present a travel document, "Fedi", proving his passage through areas officially clear of disease.

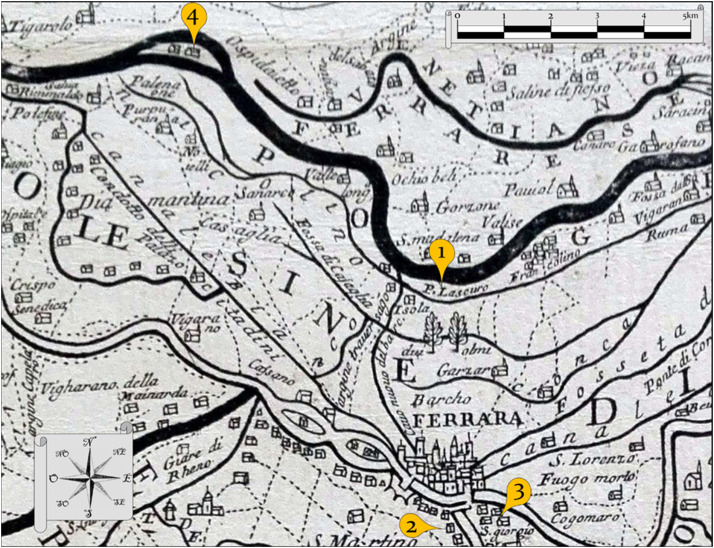

When neighboring cities reported plague outbreaks, Ferrara itself would close all gates but two, one land and one river gate, which would be manned by guards and doctors. Vital trade goods were repacked in specially built wooden canals docks and only inspected items were allowed.

Any suspected case and all who had been in contact were quarantined at one of three lazaretto, outside the walls, 5km away, or on an island 15km away. A monastery nearby was designated as an emergency hospital with hundreds of beds and stocks of supplies for major outbreaks.

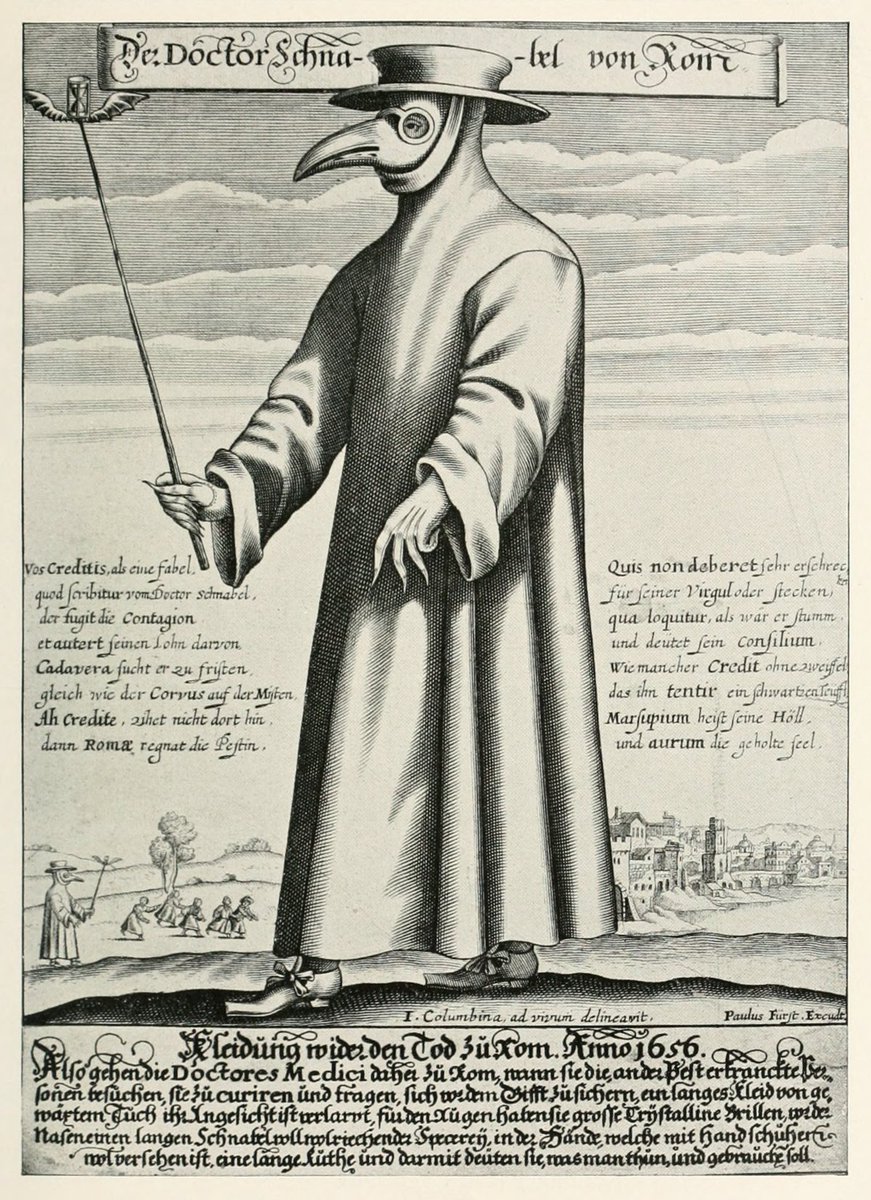

Doctors and public officials wore gowns of oilcloth that repelled lice and masks with antimicrobial herbs and sponges drenched in vinegar, with glass goggles, long gloves and boots. No public officials in the city caught the disease after their introduction.

While all around hundreds of thousands perished, Ferrara had two mild cases during the three years the outbreak lasted: a postal worker, Bartolomeo Rossi, and an unnamed school boy. Both households were quarantined and both survived, but all schools closed for two months.

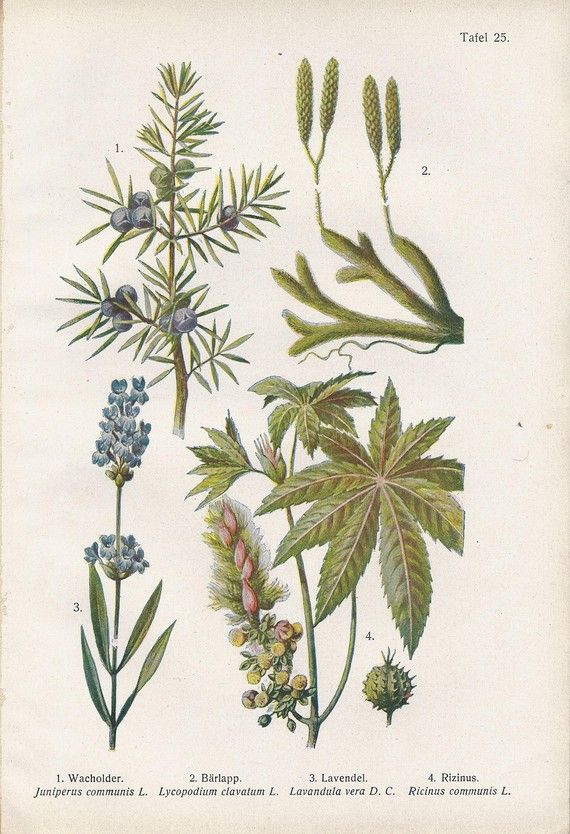

Any house with the plague was thoroughly cleaned and doused with a cocktail of 26 different herbs that together were antimicrobial, insecticidal, acaricidal (against ticks and lice, main spreader of the plague). For example, laurel, mint, sage, juniper.

These were all ingredients of the special "Composito", an anti-plague drug stored with ample reserves at all times in city hall, distributed freely to citizens in plague times, part of daily rigorous bodily cleaning routine which involved hand washing, mouth rinsing, etc.

The integrated disease management of effective borders, a vigilant health authority with full access to public funds, medicine, meant that Ferrara could not only protect itself, but also its entire area, while keeping up high volume trade, and this during a massive regional war.

(Footnote: this thread was inspired mainly by this 2019 study:)

C.B. Vicentini, S. Manfredini, D. Mares, et al., Empirical “integrated disease management” in Ferrara during the Italian plague (1629–1631), Parasitology International(2019), doi.org/10.1016/j.pari…

C.B. Vicentini, S. Manfredini, D. Mares, et al., Empirical “integrated disease management” in Ferrara during the Italian plague (1629–1631), Parasitology International(2019), doi.org/10.1016/j.pari…

I don't know if this is at all related to the current situation, but the latest available figures are... ...looking good.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh