MINI-THREAD: #Talmud-ic Names and the #NewTestament.

The Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed.) contains a noteworthy article by Louis Isaac Rabinowitz, which analyses the personal names attested in the Talmud.

The Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed.) contains a noteworthy article by Louis Isaac Rabinowitz, which analyses the personal names attested in the Talmud.

The onomastic tendencies identified by Rabinowitz share a number of significant points of contact with those of the NT’s onomasticon.

Below are some examples.

Below are some examples.

First, in the Talmud, a large number of Jews (many of whom may be Diasporised) bear both a Hebrew and a Greek/Latin-influenced name.

As examples of a Greek/Latin influence, Rabinowitz lists the names ‘Rufus’, ‘Julianus’, ‘Justus’, and ‘Aleksandri’.

As examples of a Greek/Latin influence, Rabinowitz lists the names ‘Rufus’, ‘Julianus’, ‘Justus’, and ‘Aleksandri’.

Three of these names are borne by Jews in the NT, two of whom also have a Hebrew name.

Mark mentions a Cyrenian pilgrim whose sons are named ‘Alexander’ and ‘Rufus’ (Mark 15.21).

Mark mentions a Cyrenian pilgrim whose sons are named ‘Alexander’ and ‘Rufus’ (Mark 15.21).

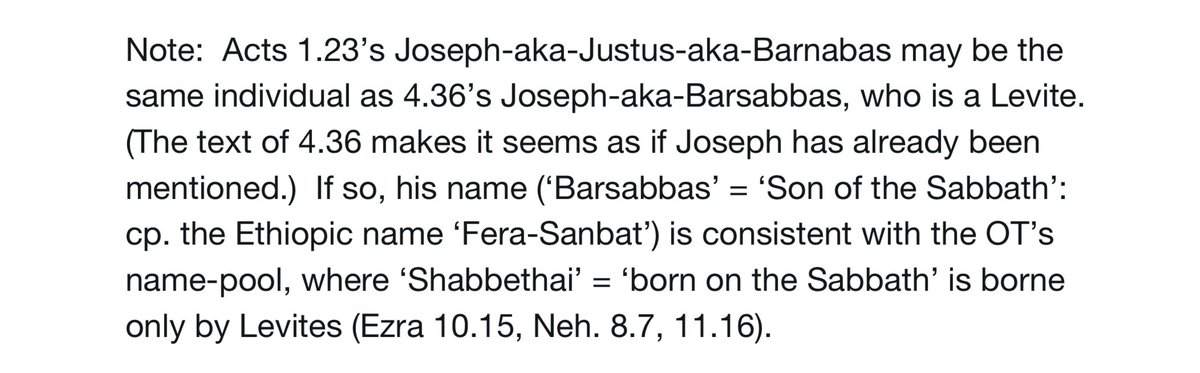

The book of Acts mentions a disciple named ‘Joseph’, who is also named ‘Justus’ (and given the name ‘Barnabas’ by the apostles) (Acts 1.23).

And Paul has a fellow-labourer by the name of ‘Jesus’ (a Jewish name), who also bears the (Roman) name ‘Justus’ (Col. 4.11).

And Paul has a fellow-labourer by the name of ‘Jesus’ (a Jewish name), who also bears the (Roman) name ‘Justus’ (Col. 4.11).

Second, in the Talmud, the names of Israel’s Rabbis involve a remarkably wide range of name-types, included among which are:

🔹 traditional Biblical names, such as ‘Simeon’, ‘Joshua’, and ‘Judah’,

🔹 traditional Biblical names, such as ‘Simeon’, ‘Joshua’, and ‘Judah’,

🔹 names which are not borne by Biblical ‘worthies’, yet which are nevertheless Biblically attested, e.g., ‘Hillel’, ‘Gamliel’, and ‘Johanan’,

🔹 Greek names, such as ‘Antigonus’ and ‘Avtalyon’,

🔹 Greek names, such as ‘Antigonus’ and ‘Avtalyon’,

🔹 Grecised equivalents of Hebrew names, such as ‘Dositheus’ for ‘Nethaniel’, which do not always run in families (cp. the case of ‘Dostai b. Judah’),

🔹 Roman names, such as ‘Julianus’, and

🔹 Roman names, such as ‘Julianus’, and

🔹 shortened forms of Hebrew names (in Rabinowitz’s terms, ‘Aramaised names’), such as ‘Yose’.

Equivalents of all of these name-types can be found in the NT.

Relevant examples include:

🔹 traditional Biblical names, such as a mass of Sim(e)ons and Judahs,

🔹 less well-known yet nevertheless Biblically-attested names, such as various Johns and a Gam(a)liel (Acts 5),

Relevant examples include:

🔹 traditional Biblical names, such as a mass of Sim(e)ons and Judahs,

🔹 less well-known yet nevertheless Biblically-attested names, such as various Johns and a Gam(a)liel (Acts 5),

🔹 Greek names such as ‘Andrew’, ‘Philip’, and ‘Alexander’,

🔹 Grecised names, such as ‘Sopater’ (from the Hebrew name ‘Abishua’) (Rom. 16.21),

🔹 Grecised names, such as ‘Sopater’ (from the Hebrew name ‘Abishua’) (Rom. 16.21),

🔹 Roman names, such as ‘Paul’ (whose Hebrew name is ‘Saul’), which do not always run in families (e.g., in the case of ‘Rufus b. Simon’), and

🔹 abbreviated Hebrew names such as ‘Joses’ (Matt. 13.55, 27.56) (which appears as ‘Joseph’ in some copies of Matt. 27.56), ‘Simon’ (i.e., ‘Simeon’ minus an ‘ayin’), and ‘Zebedee’ (from ‘Zebadiah’).

Third, in the Talmud, Rabbis systematically avoid certain names which one would *expect* to be very popular.

Not a single rabbi, Rabinowicz says, is known by the name of ‘Moses’, ‘Abraham’, ‘Israel’, ‘David’, or ‘Solomon’,

which is also true of the characters of the NT.

Not a single rabbi, Rabinowicz says, is known by the name of ‘Moses’, ‘Abraham’, ‘Israel’, ‘David’, or ‘Solomon’,

which is also true of the characters of the NT.

Hence, while *some* famous names are very common in the Talmud (e.g., ‘Judah’, ‘Joseph’, etc.), others are off limits,

which is clearly reflected in the NT.

which is clearly reflected in the NT.

Most of the prophets’ names are likewise avoided by the Rabbis (as they also are in the NT),

with the exception of Jonah, Zechariah, and Haggai, two of which are attested in the NT (‘Zechariah’ the father of John the Baptist, and ‘Simon Peter b. Jonah’).

with the exception of Jonah, Zechariah, and Haggai, two of which are attested in the NT (‘Zechariah’ the father of John the Baptist, and ‘Simon Peter b. Jonah’).

And a final group of avoided names are those of angels, e.g, ‘Gabriel’ and ‘Michael’, both of which are mentioned in the NT though are not borne by humans.

In sum, then, Talmudic and NT names seem to be drawn from a similar name-pool. They exhibit:

a similar mix of names and name-types,

similar Greek/Latin names (e.g., ‘Alexander’), which one would not necessarily expect to be attested in Israel,

a similar mix of names and name-types,

similar Greek/Latin names (e.g., ‘Alexander’), which one would not necessarily expect to be attested in Israel,

and similar exceptions (e.g., ‘Moses’), which one *would* expect to be attested in Israel.

For a more rigorous and insightful discussion of similar issues (based on data from inscriptions, legal documents, etc., etc.), see pp. 64–78 in @DrPJWilliams’ latest book,

For a more rigorous and insightful discussion of similar issues (based on data from inscriptions, legal documents, etc., etc.), see pp. 64–78 in @DrPJWilliams’ latest book,

which now would seem a good time to read (though you can probably manage without the same author’s ‘Early Syriac Translation Technique’ for the foreseeable future).

THE END.

amazon.com/Can-Trust-Gosp…

THE END.

amazon.com/Can-Trust-Gosp…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh