As we pick up the story, Jesus’ fame has begun to surpass John’s,

which has resulted in large numbers of (water) baptisms (4.1–3).

as it will do in 4.3ff.’s events.

It is ‘necessary’ (δεῖ) for him, we’re told, to pass through Samaria.

But ‘necessary’ in what way?

Yet Jesus doesn’t appear to be in a rush (cp. 4.40, where Jesus decides to stay in Samaria for two extra days).

He has recently spoken about the ‘need’ (δεῖ) to be born from above (3.7) and for the Son of Man to be lifted up (3.14).

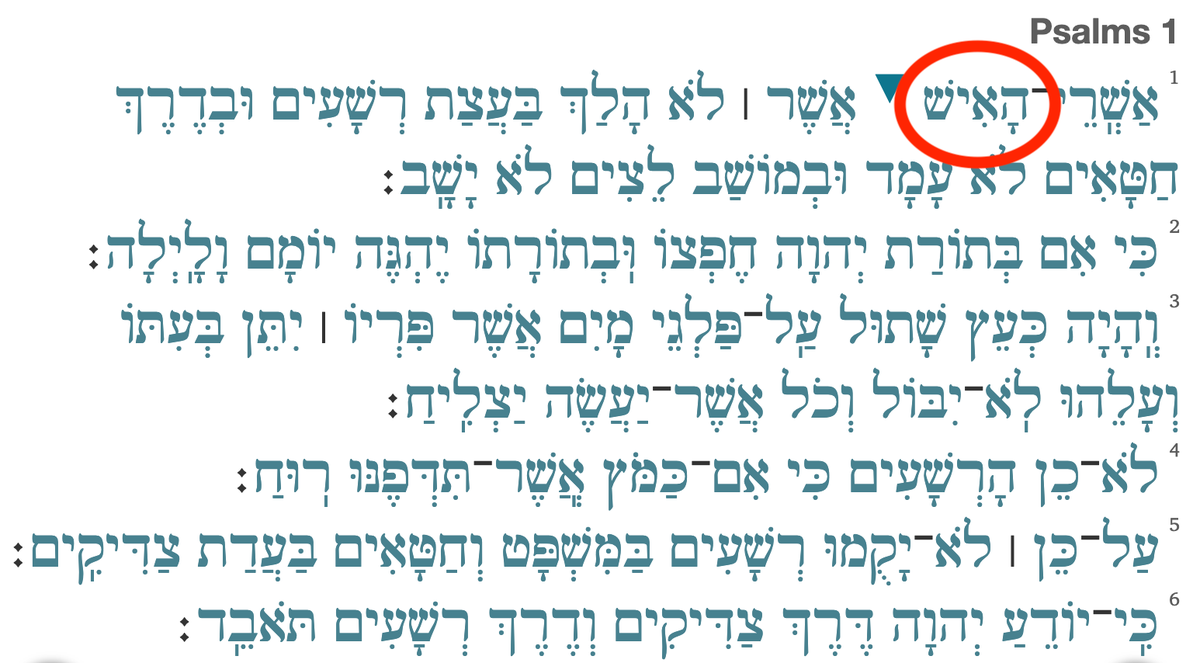

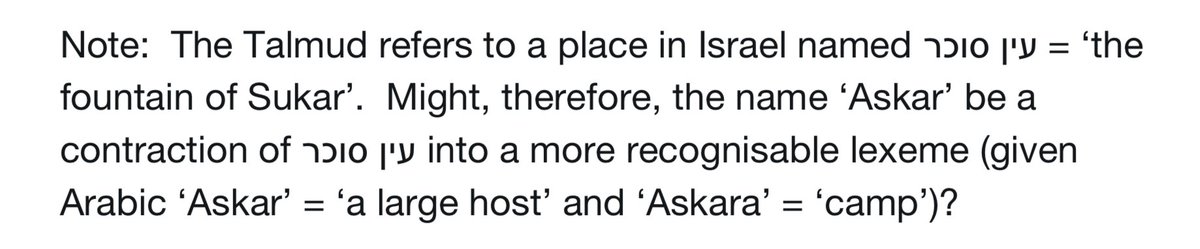

The region of ‘Sychar’ (Συχάρ) is typically identified with the modern-day town ‘Askar’ (عسكر),

which is thought to have been occupied in Jesus’ day.

which makes it a good fit with the text.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacob%27s…

whom he meets at midday (i.e., ‘at the sixth hour’).

We might think, for instance, of a patriarch who went to a foreign land long ago in search of a wife,

and met a woman in the vicinity of a well (at midday) (Gen. 29).

And in some senses they do.

Like Jacob, Jesus helps the woman whom he meets to obtain water.

And, also like Jacob, Jesus raises the issue of marriage.

Moreover, the events of our text differ from those of Gen. 29 in a number of important ways.

While Rachel introduces Jacob to her father, Jesus seeks to introduce the Samaritan woman to *his* Father.

And, soon afterwards, the woman is again surprised when, in response to her hesitancy, Jesus offers *her* water (4.10).

It is ‘living water’ (ὕδωρ ζῶν),

which is presumably the equivalent of the Hebrew expression ‘mayim chayim’ (מים חיים).

Or it could be understood in a more metaphorical manner.

the answer to which, she will soon discover, is Yes!

since Jesus offers the woman water which *permanently* satisfies, and which ‘wells up’ to eternal life (4.14).

When Jacob removes the stone from the mouth of Laban’s well, its water rises up to its surface and ‘overflows’ (טוף), and continues to do for the next twenty years,

As such, Jesus’ offer of water which ‘overflows to eternal life’ portrays him as a ‘greater than Jacob’.

What Jacob provides for twenty years, Jesus is able to provide in perpetuity.

When Jacob seeks to roll its stone away, he is told it is not yet time to do so.

The well can only be accessed *after* midday (the sixth hour), once Laban’s various flocks have been gathered together.

The hour for the water of life to be outpoured, Jesus says, is now present (4.23).

And Jesus has come precisely in order to gather God’s various flocks together (10.16).

which I plan to get to next time round.

To close, however, let’s consider a few features of John’s text which exhibit a noteworthy consistency with—and awareness of—the Samaritan culture/theology of the day (as best we can reconstruct it).

Rabbinic texts tend to take a low view of the Samaritans.

Indeed, many texts forbid intermarriage with them (Keener 2010:598).

Rabbinic texts frequently compare the Torah to water and a good Torah teacher to a well (e.g., m. Avot 1.4, 11, 2.8, Mek. Vay. 1.74ff.);

Rather, John’s imagery is consistent with (what we know of) the imagery of the day.

The Samaritans were aware of ‘the Jewish version of their ancestry’ (recorded in 2 Kgs 17.24–41).

More specifically, they claimed to be able to trace their ancestry back to Joseph (cp. Gen. Rab. 94.7) (though not to the Rabbis’ satisfaction).

Consequently, the Samaritans awaited the appearance of ‘a prophet like Moses’ (per Deut. 18.18),

‘When Messiah comes’, the woman says, ‘he will tell us all things’ (4.25; cp. also 4.29, 39).

In sum, then, while material unique to John is frequently viewed as the product of a Johannine community far removed from Israel, some of it at least exhibits the same indicators of trustworthiness and familiarity with life in Israel as the Synoptic material.

But they are nowhere mentioned in the NT epistles, and are only rarely mentioned in the Gospels and Acts,

THE END.