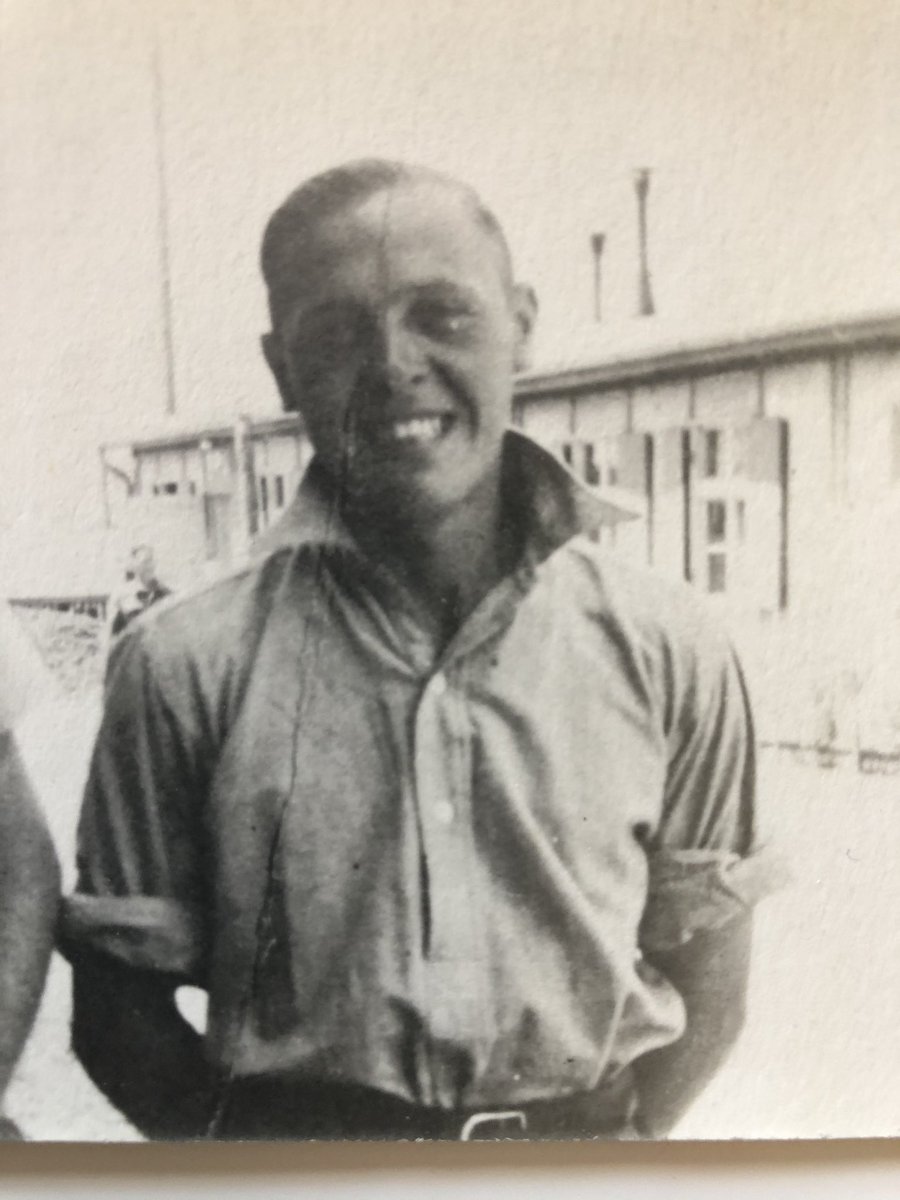

My dad. He got on with life after he came back from Germany. He’d been there five years, a PoW at Lamsdorf, Stalag VIIIB

I’ve no idea what he thought or felt on #VEDay . Relief? Probably. Like thousands of others of the BEF in he was captured in 1940 and the years were long and hard.

All non-Officer PoWs worked. They had no choice, and it was hard graft. And without the Red Cross food parcels there was starvation. This was true in 1940 - as it was in 1945. Dad was amongst the first to arrive at VIIIB, and he was put to work

Pictures sent home from the camps told of organised sport and concert parties. A holiday camp, right? Some soldiers even received letters that called them shirkers. The reality was so different

Postcards home said nothing of the privations, and the information given to relatives was upbeat. How could it be anything else? But as the Soviet prisoners were marched by in rags and beaten in front of my father, the everyday reality was sinister

And as the war came to its conclusion, the men in the east were set to march west. It was a brutal march in winter conditions, with frostbite, beatings and starvation.

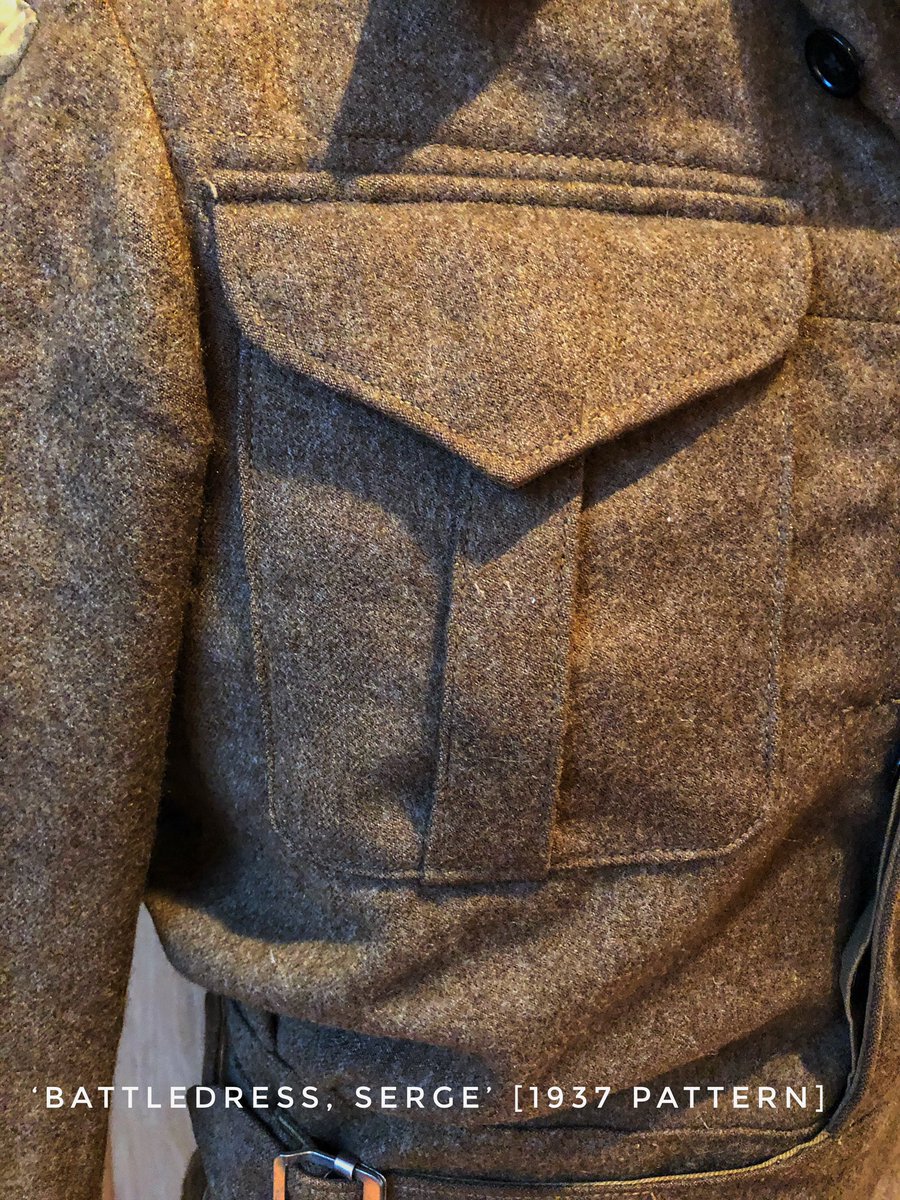

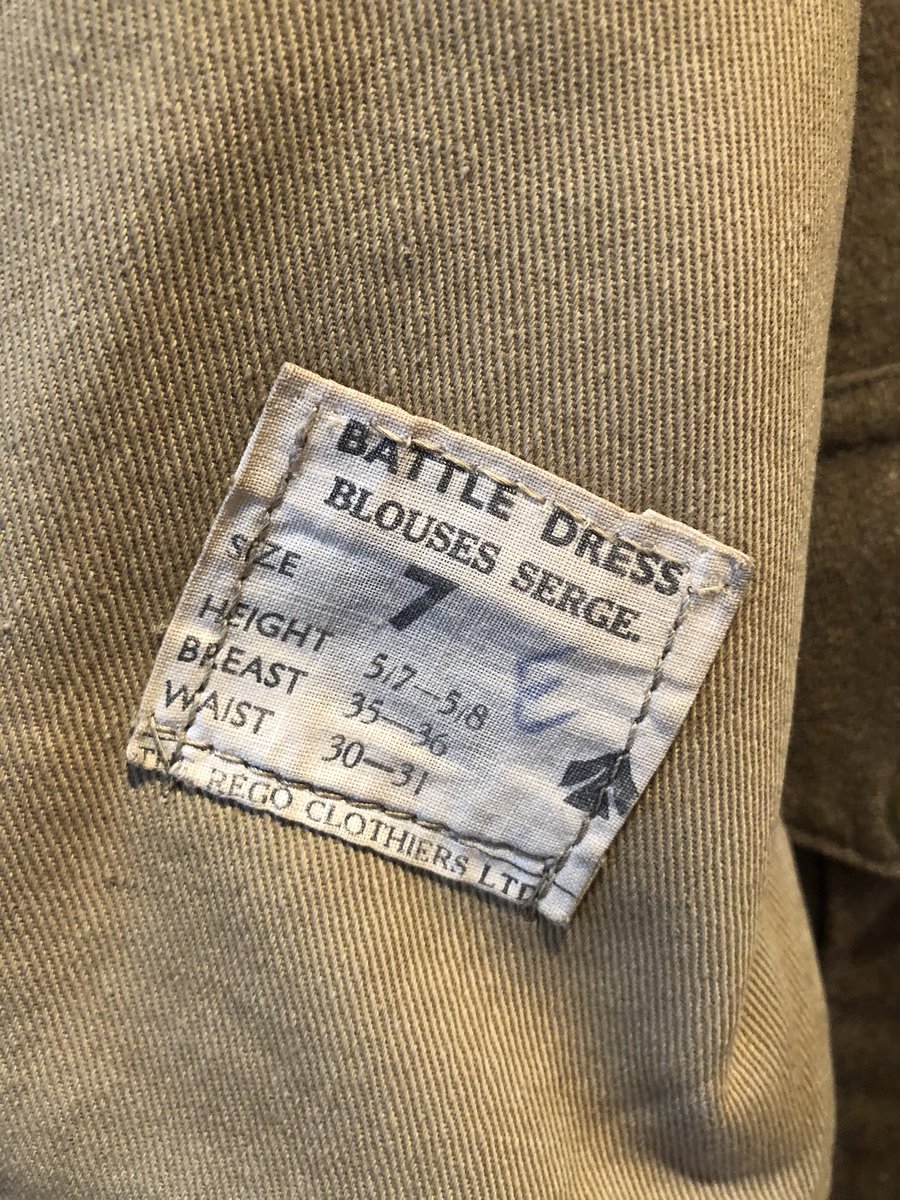

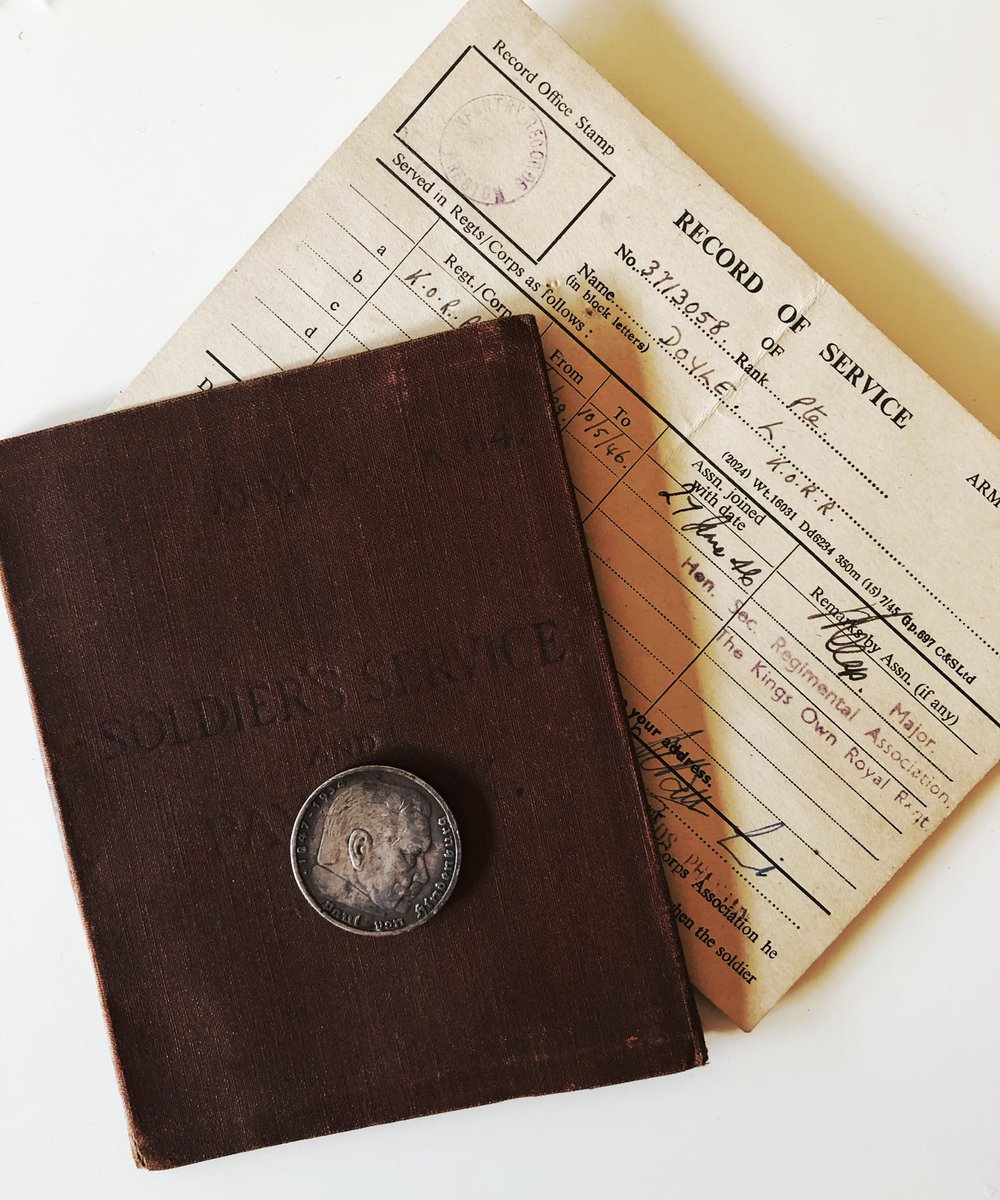

When dad got home they gave him these. Did he care about them? No. (I rescued them from a button box when I was 6 years old). Did he want to remember? No.

But in the street in Birkenhead where we were born are the faint painted letters: ‘Welcome Home Les’

My Dad: My Hero.

But in the street in Birkenhead where we were born are the faint painted letters: ‘Welcome Home Les’

My Dad: My Hero.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh