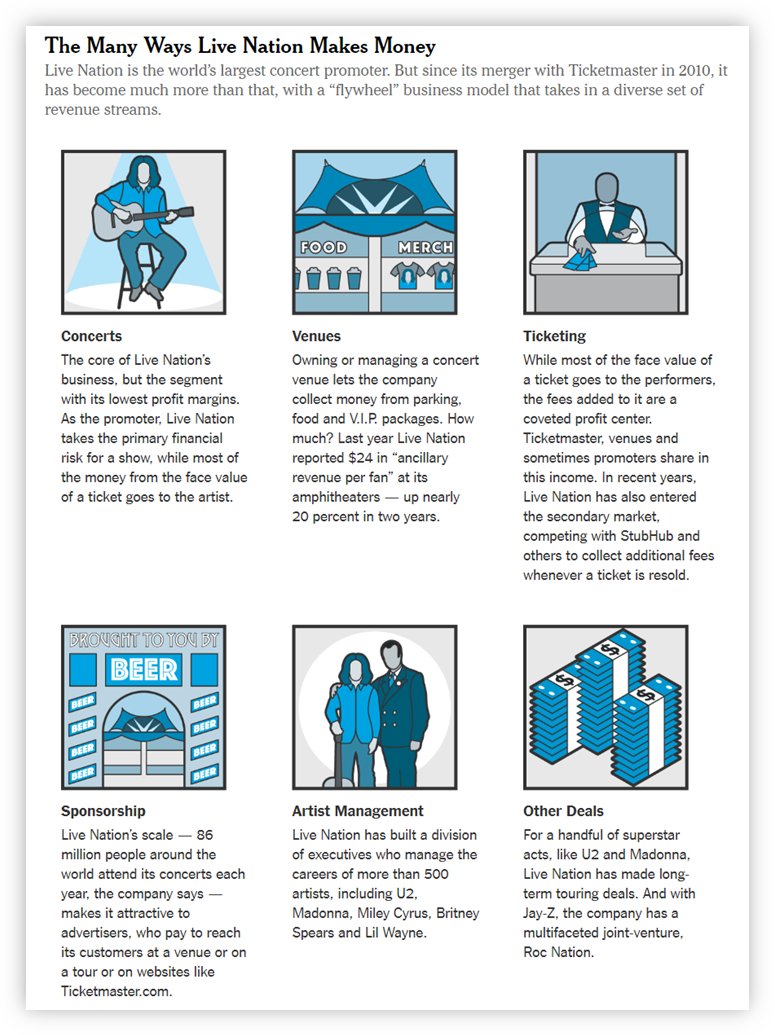

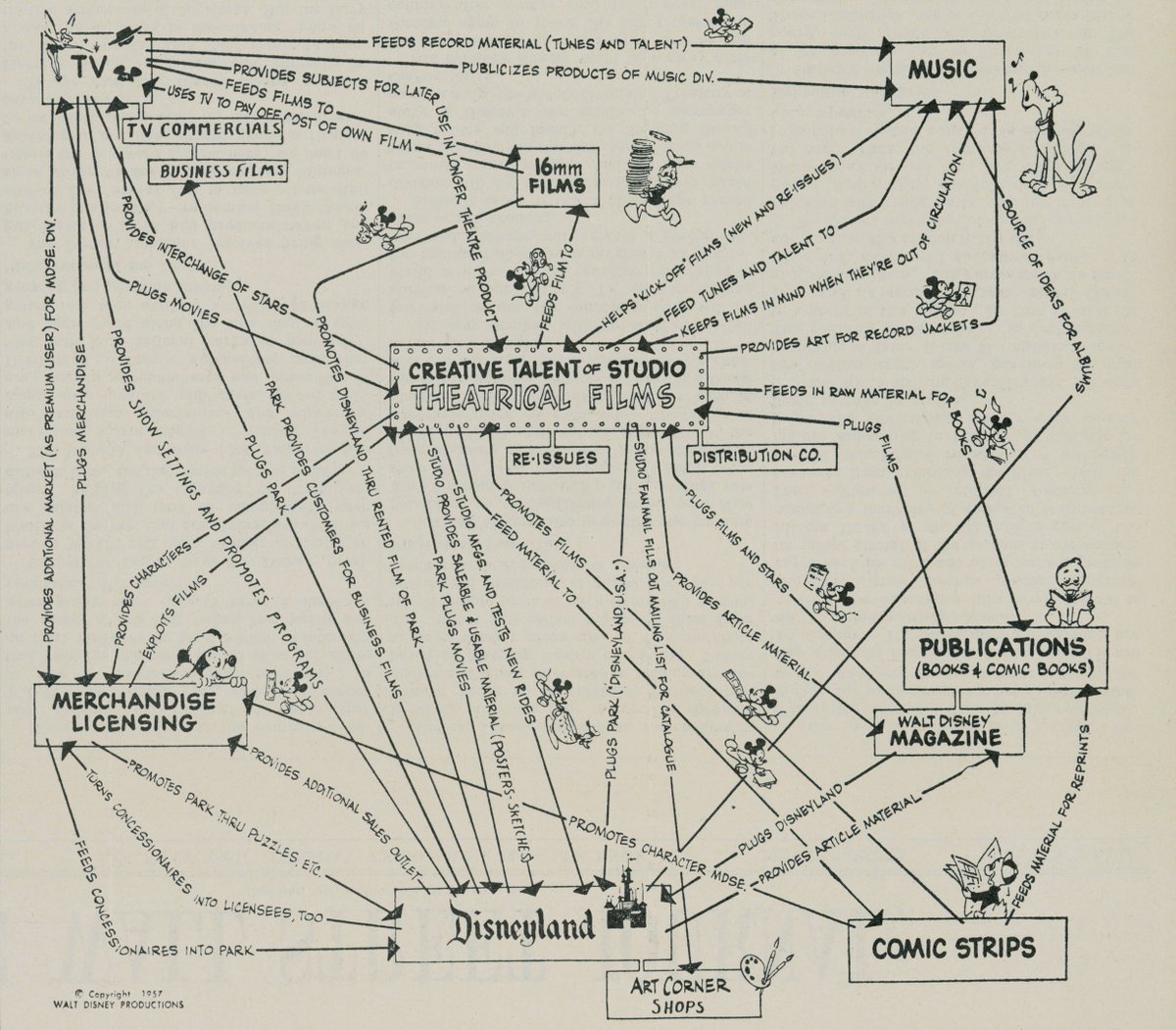

The more good options a company has — enabled by owning the proper audience, tech, skills, and capital — the harder it is to knock down. Optionality is also a force multiplier that allows businesses to grow faster and longer than most would predict.

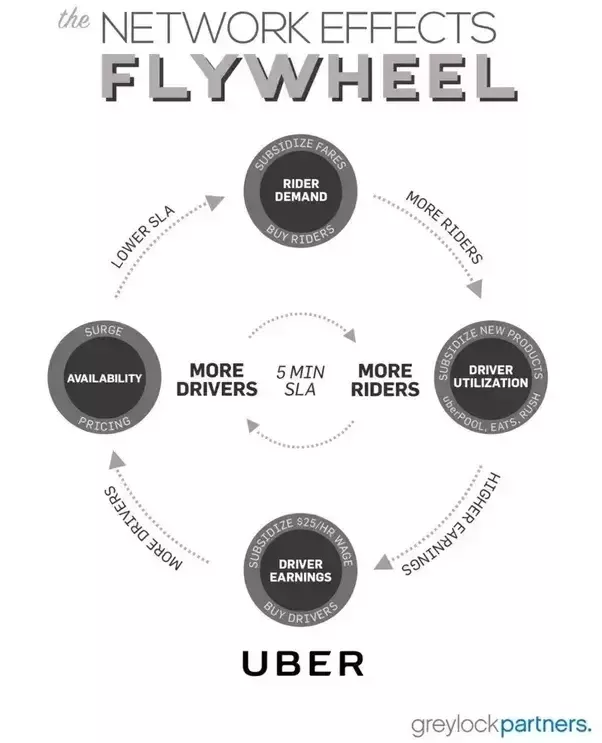

Aggregators have 1) a direct relationship with users, 2) ~zero marginal costs, and 3) demand-driven + multi-sided network effects with decreasing acquisition costs. If a company has all three, they can conquer winner-take-all markets.

stratechery.com/2017/defining-…

- Create useful, transparent & often user-generated content in opaque markets

- Use that content to dominate SEO & capture demand

- Get those new users to sign up + contribute

It's a flywheel that enables other advantages to kick in kwokchain.com/2019/04/09/mak…

Getting paid by customers before needing to pay suppliers or fulfill a service is a great trait, especially when a company can use its payables to accelerate high-returning reinvestment.

Float isn’t talked about nearly enough regarding internet companies.

When belief in a company transcends fandom and borderlines on religion, rationality barely matters. Irrational pricing is what enables companies (like Tesla) to raise capital, tackle new ideas, and stir up exuberance again. Rinse, repeat.

Tip: When you spot reflexivity, ride the wave, don’t fight it. But be mindful of when fervor has run its course.

Companies that pursue complex, challenging goals face fewer qualified competitors than those who chase easier goals. It also takes longer for copycats to catch up, which helps entrench the top dogs.

Ex: rockets, EVs, elegantly combining hardware + software

A strong supply chain that covers multiple countries — with different laws, languages, and logistics challenges — is hard to beat, especially if it got a head start and operates in a challenging region. (Ex: MercadoLibre)

Instead of focusing on “first movers” focus on the “first to scale." Determine who’s figured a market out, not who’s first to see it. It’s often not the same company.

With plenty exceptions, first movers often time markets too early or make naive mistakes.

If a network effect business moves fast enough, there’s a tipping point at which competing becomes impossibly hard.

If the network's content is user-generated, hitting escape velocity also means it’ll never need to pay for content to attract demand.

The ability to raise prices is great, but in the world of bits where variable costs approach zero and scale brings high margins, being able to reduce prices in ways others can’t is a sure way to maintain and grow market share.

Changing how people pay for products or services is sometimes just as powerful as transforming the underlying technology.

It comes in various forms: bundling/unbundling, democratizing, payment timing, freemium, cutting out middlemen, etc.

Some companies are better positioned to benefit from change or chaos than others.

- Is the company's mission more or less relevant in the future?

- Do its leaders thrive in change?

- Can it financially weather a storm and opportunistically deploy capital?

Most companies are great at one thing: internal building, serial acquiring, etc.

Many of the best companies, however, have a keen and humble sense of when to build, buy, and partner — plus when to double down and when to let go.

The advantage here is less that marketing costs are low and more that capital is freed up to be reinvested elsewhere (R&D, acquisitions, etc.). Over multiple years, the gap between those who can afford to heavily reinvest and those who can’t widens.

When great employees stick around…

- More internal knowledge retains over time

- Companies can spend less time on hiring / training

- Internal promotions become more viable

- Long-term thinking is more widespread

Change is hard, especially when tackling existential opportunities means sacrificing profits.

It’s why founder-leaders are often powerful. They’re missionaries who think long-term vs mercenaries who exist to collect paychecks without stirring up drama.

“Being wrong might hurt you a bit, but being slow will kill you." @JeffBezos

Not only must companies embrace change, but they need to embrace changing quickly.

Speed is also relative. Admire companies who make their competitors look slow.

Companies whose brands blur with language — especially as verbs — often have decent staying power. It’s also free marketing.

“Google it,” “Slack me,” “I’ll Uber over,” “put on a Band-Aid,” “grab a Kleenex,” “Netflix and chill,” etc.

Many platforms need rules to facilitate proper behavior. The more platforms crack down or invade privacy, though, the more people will seek out less restrictive alternatives.

In some ways, the open-web is suffering. In others, it's just getting started

Pick a company. Then snap your fingers and imagine that it disappears. Does it leave a huge void? Do people deeply miss it?

It’s a brilliantly simple way to conceptualize how important and entrenched a business has become.

Some companies have little to no competition, even at smaller market caps. This is usually a result of other competitive advantages (+ good fortune) and should never be overlooked.

If I had to invest based on one factor, this would be high on the list

Connects to one of my semi-controversial investing beliefs: “Companies with deep competitive advantages are less interesting than companies whose advantages are only starting to shape up.”