Think flying was crowded, expensive, and lacking in glamour before Covid-19? It's going to be a whole lot worse in future:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl… #AvGeek

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl… #AvGeek

It's hard to overstate how utterly coronavirus is likely to reshape the global aviation industry, and the results aren't likely to please passengers.

That aviation service you were bitching about in 2019? It was far better value than what you'll experience for years to come.

That aviation service you were bitching about in 2019? It was far better value than what you'll experience for years to come.

The economy-class service you complained about was being *subsidized* by business class.

Premium-class tickets account for 30% of airline revenue, despite only amounting to 5% of seats.

Business travel has disappeared with the virus and some of it will *never* come back.

Premium-class tickets account for 30% of airline revenue, despite only amounting to 5% of seats.

Business travel has disappeared with the virus and some of it will *never* come back.

Then consider that the aviation industry invests a decade in advance in planes, airports etc.

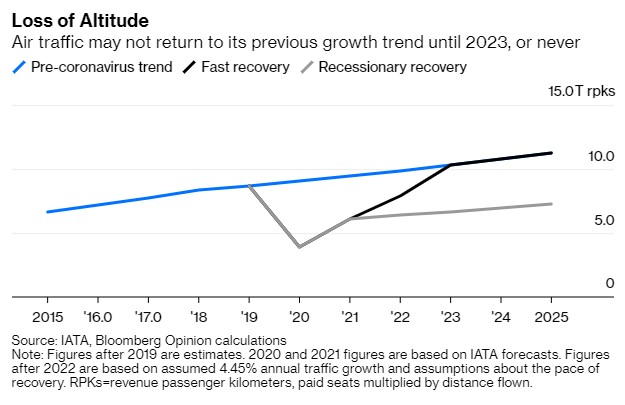

When traffic returns to 2019 levels (unlikely before 2023), it will be facing an industry it expected to be up to a fifth bigger, based on 4%-5% annual growth rates.

When traffic returns to 2019 levels (unlikely before 2023), it will be facing an industry it expected to be up to a fifth bigger, based on 4%-5% annual growth rates.

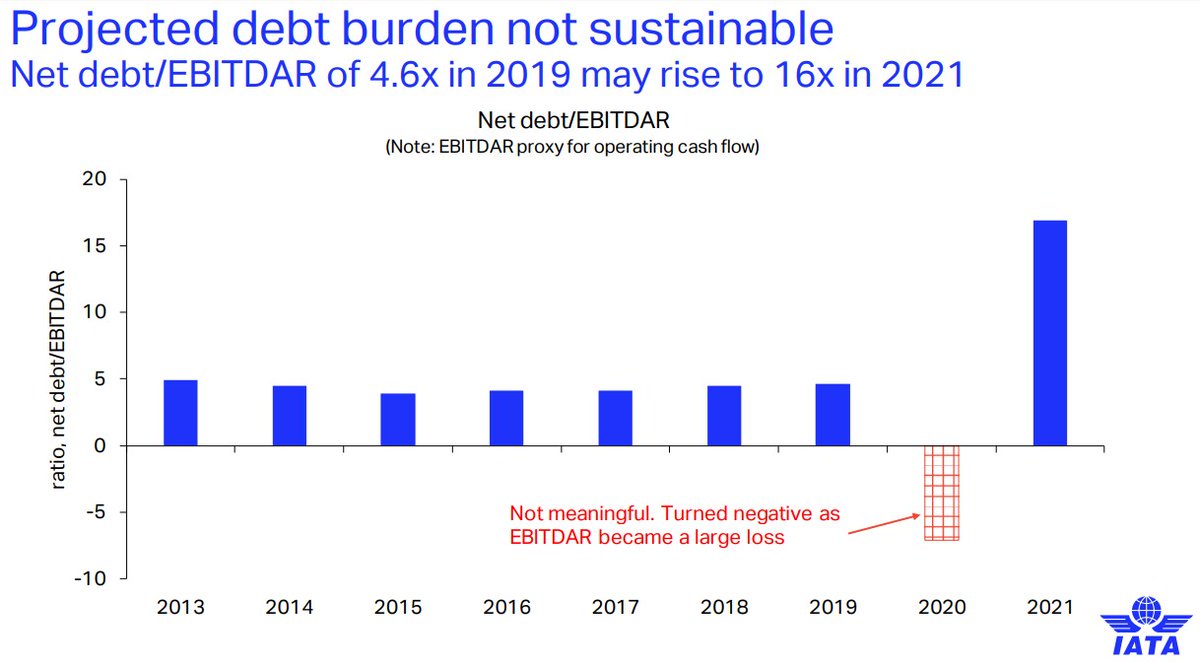

The debt burden that airlines are racking up is completely unprecedented.

Generally you would worry about any non-financial company whose net debt was more than 4x or 5x its Ebitda.

For airlines the equivalent will be 16x next year. Unheard-of levels -- for a whole industry!

Generally you would worry about any non-financial company whose net debt was more than 4x or 5x its Ebitda.

For airlines the equivalent will be 16x next year. Unheard-of levels -- for a whole industry!

Link for that here: iata.org/en/iata-reposi…

As a result I think three types of airlines are going to emerge from this: Ryanair, Etihad, and Air India.

None of those should be very appetising business models.

None of those should be very appetising business models.

https://twitter.com/davidfickling/status/1278574072658489344

The Ryanairs of the world will probably do best. Budget carriers have low cost bases and their workers don't have good union representation. Brutally, that means it will be easy for them to cut costs.

They're also focused on the sort of short-haul and domestic markets that don't involve many border crossings. Europe appears to be recovering faster than other places. Domestic Chinese, Japanese and Australian operations will also do better: iata.org/en/iata-reposi…

Some of them may even be able to survive without government support, or with only the sort of broad support available to every company -- payments for keeping employees employed rather than firing them, tax cuts, etc.

At the other extreme you have the likes of Emirates, Etihad, Singapore Airlines and Cathay Pacific. These airlines have *no* domestic markets and are entirely dependent on their status as global hub carriers. Fundamentally things will be very grim indeed for these airlines.

Just crossing a single international border is hard enough as it is. Getting people from, say, Milan to Melbourne via Dubai (once the bread-and-butter of a global hub carrier) is just an absolute mess of potential quarantine breaches, and will remain so for years.

Luckily for almost all of the global hub carriers, they exist for strategic political reasons as agents of their countries' long-term economic development and are mostly state-owned. Singapore and Dubai will do almost anything to prop up their flag carriers.

You can't say the same for Cathay Pacific, though, whose very existence as an emblem of Hong Kong's difference is in some ways an affront to Beijing.

It got its bailout recently, but things will be tough if it needs further funds.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

It got its bailout recently, but things will be tough if it needs further funds.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

Then in the middle you have other carriers -- ones that are neither budget airlines nor formal national champions but independent commercial carriers, likely to need support from the governments that once privatized them (except in the U.S., where they were always independent).

It's going to be very, very hard for them. It's hard to escape the notion that many will turn into versions of Air India, Malaysian Airlines or Alitalia -- state-owned, debt-burdened, with poor service, a shadow of their old selves being propped up to support their workforces.

How will airlines escape this? One thing that will help paying down debt is that many competitors will go bankrupt. That will mean the survivors are in a less competitive market and can gradually raise prices to more profitable levels.

They'll also look to increase revenues from all the bits of flying where they don't face competition -- ie. everything but tickets. So expect to pay more for baggage fees, legroom, window seats, onboard food and drink, access to the entertainment system, frequent flier points...

Short-haul flying, whether on a discount or full-service carrier, is likely to look a lot more like being on a budget carrier in future. Long-haul flying is likely to be even more expensive, and don't expect any glamour.

One other thing. Governments shouldn't hand out all this largesse for free. About 3/4 of flights take off or land in the U.S., Europe or China. Those governments have a once-in-history chance to impose a global industry carbon price. They should take it.

That will just add to the price of tickets the way fuel surcharges did in the early 2010s, but it will encourage airlines to use more biofuels as a competitive advantage and encourage OEMs to develop some of the blue-skies low- or zero-carbon technologies being dreamed of.

Either way, though, the near future of aviation is likely to be nasty, brutish, and short-haul. Read the whole story here: bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh