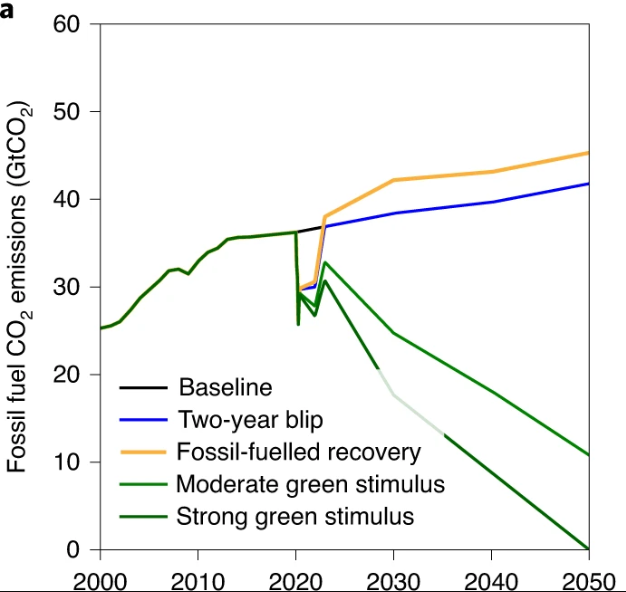

"[a]n economic recovery tilted towards green stimulus and reductions in fossil fuel investments, it is possible to avoid future warming of 0.3 °C by 2050."

(thread)

nature.com/articles/s4155…

(thread)

nature.com/articles/s4155…

I do have a few problems with this framing...

The use of the word "tilted" implies are rather minor shift, but the "strong green stimulus" is actually a ~1.5°C pathway ("moderate" is a ~2°C pathway).

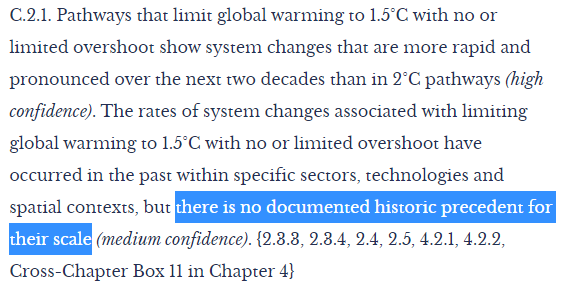

I thought 1.5°C required a transformation? Did #SR15 get it wrong?

2/

The use of the word "tilted" implies are rather minor shift, but the "strong green stimulus" is actually a ~1.5°C pathway ("moderate" is a ~2°C pathway).

I thought 1.5°C required a transformation? Did #SR15 get it wrong?

2/

#SR15: "Pathways limiting global warming to 1.5°C with no or limited overshoot would require rapid and far-reaching transitions in energy, land, urban and infrastructure (including transport and buildings), and industrial systems (high confidence)"

ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/s…

3/

ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/s…

3/

Is this the message for governments: "with an economic recovery tilted towards green stimulus and reductions in fossil fuel investments"?

Just green your stimulus a bit, & 1.5°C is done & dusted? I think that downplays the challenge somewhat?

(@piersforster?)

4/

Just green your stimulus a bit, & 1.5°C is done & dusted? I think that downplays the challenge somewhat?

(@piersforster?)

4/

Another issue I have with the framing is that I would think of "recovery" as being a short-burst (maximum a few years) of investment to achieve whatever objective ("recovery").

But, these "green stimulus" pathways are continuous investments to 2050. This is permanent change!

5/

But, these "green stimulus" pathways are continuous investments to 2050. This is permanent change!

5/

Of course, we want permanent change, but I don't think this meshes so well with the term "recovery".

If I recover from being sick, does that mean I spend the rest of my life in intensive care?

I need to change my diet/lifestyle, permanently, not recover & return to normal?

6/

If I recover from being sick, does that mean I spend the rest of my life in intensive care?

I need to change my diet/lifestyle, permanently, not recover & return to normal?

6/

Current pledges put us on a path for 1.8°C or so in 2050, & if we follow a 1.5°C pathway, we shave off 0.3°C. This is still 0.3°C higher than where we are today (~1.2°C).

I think this is an important point to focus on, but the challenge is communicating these changes.

7/

I think this is an important point to focus on, but the challenge is communicating these changes.

7/

The climate is a slow moving system, so deep mitigation (purple in top figure) leads to small & delayed changes in the temperature response (bottom figure).

This is my attempt to communicate the challenge, based on the SSP database (of course, too complex for lay audiences).

8/

This is my attempt to communicate the challenge, based on the SSP database (of course, too complex for lay audiences).

8/

Noting that the authors based the reference pathway on where we are heading (as opposed to the worst case RCP85-type pathway). This is the correct approach!

Using a RCP85-type pathway as a reference would make the benefits of mitigation ≫0.3°C...

nature.com/articles/d4158…

9/

Using a RCP85-type pathway as a reference would make the benefits of mitigation ≫0.3°C...

nature.com/articles/d4158…

9/

Overall, a good & useful study (thanks @piersforster & team).

I just got thrown by the "tilted" term & "strong green stimulus" meaning ~1.5°C pathway. I am interested how other people interpreted this? Thoughts?

10/10

I just got thrown by the "tilted" term & "strong green stimulus" meaning ~1.5°C pathway. I am interested how other people interpreted this? Thoughts?

10/10

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh