Historically, the vast majority of Bible commentators took the book of Daniel to represent the memoirs of a 6th cent. exiled prophet (named Daniel).

In recent times, that situation has pretty much reversed.

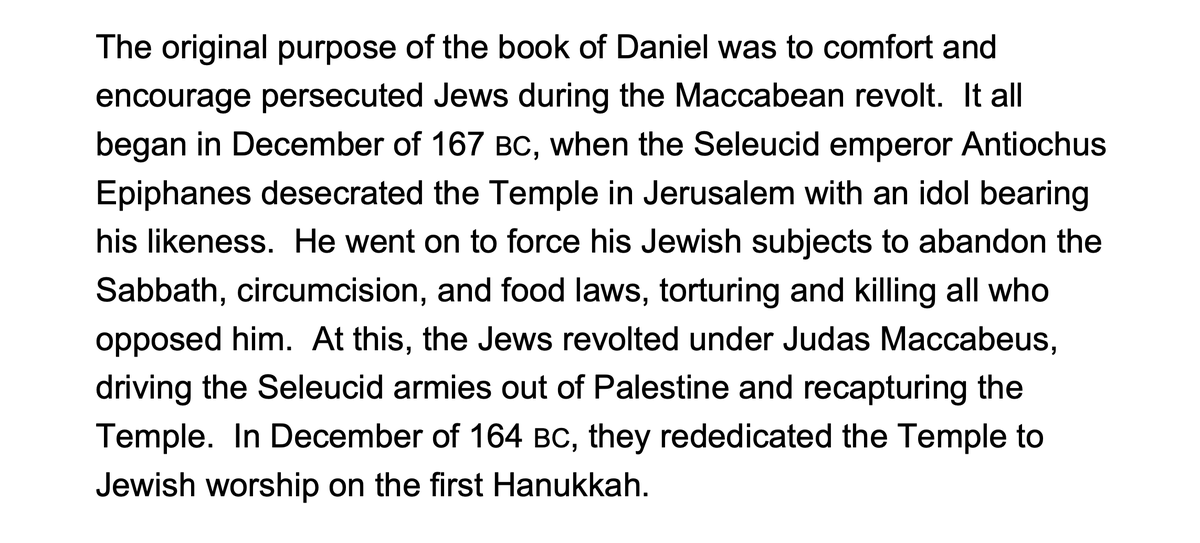

First, however, let’s make sure we’re clear on what the Maccabean Hypothesis asserts.

On the Maccabean Hypothesis—or, for short, ‘the MH’—, the book of Daniel ain’t what it appears to be.

Specifically, it’s not a collection of visions/prophecies revealed to a 6th cent. BC exile.

and (on that basis?) came to believe the Messianic era was just around the corner.

Paragraph 1:

Daniel, they say, is inaccurate when he refers to life in 6th cent. Babylon,

and becomes wildly inaccurate when he refers to post 165 BC events.

but is evidently *not* aware of the Temple’s reclamation in 164 BC (and the demise of Antiochus),

Advocates of the MH also advance independent lines of evidence in support of their hypothesis, included among which are:

🔹 indicators of lateness in Daniel’s vocabulary,

🔹 four-empire schemas elsewhere in the ANE,

🔹 Daniel-like documents in the Dead Sea Scrolls (e.g., Pseudo-Daniel), and

As such, advocates of the Maccabean Hypothesis are able to mount a persuasive cumulative case for their view.

So then.

What can be said by way of response to the Maccabean Hypothesis?

Well, many things *could* be said.

We *could*, for instance, examine various ‘indicators of lateness’ in Daniel’s Aramaic,

On the Maccabean Hypothesis, it’s hard to see how the book of Daniel could have made its way into the canon of Scripture and/or come to be known as the work of ‘Daniel the Prophet’.

a] that Antiochus would conquer Egypt (11.42–43);

b] that Antiochus would perish soon afterwards somewhere in Israel (11.44–45); and

c] that the Messianic era would begin soon afterwards (12.1ff.) (e.g., Porteous 1965:13).

Antiochus never conquered Egypt, nor did he die in Israel.

And when, acc. to Daniel, the Messianic age was due to begin, the Jewish people found themselves confronted by a large Seleucid army (led by Antiochus’s son).

Biblically, however, the test of a prophet is not his level of confidence in God, but the accuracy of his prophecies (Deut. 18.20–22),

which is a test Daniel spectacularly failed.

True, given sufficient time and dedication, Daniel’s supporters could no doubt have rescued his prophecies (by various hermeneutical maneouvres).

While loyalty to a long-cherished religious text is understandable, it is doubtful whether the supporters of such a recently born (and embarrassed) prophet as Daniel would have felt a great deal of loyalty to him.

Indeed, the Maccabean Daniel’s prophecies lavish little praise on the people of his day.

and what little they say is highly ambiguous (Collins 1993:66–71):

and a Maccabee-esque group are said to offer the wise ‘a little help’ (11.34),

Furthermore, the theology of chs. 2–6 is not very Maccabee-friendly,

What made Daniel’s so special?

Late 2nd cent. BC copies of Daniel have been discovered at Qumran (where they are accord the same status as Scripture), the existence of which requires a remarkable sequence of events to have transpired.

🔹 finalised (in Jerusalem) in 165 BC (e.g., Newsom 2014:21),

🔹 reinterpreted in the aftermath of 164–160’s battles (against Antiochus’s successors),

🔹 copied,

🔹 disseminated at least as far afield as Qumran, and

And all these things need to have taken place within the space of fifty years or so, which is hard to imagine (to say the least).

It’s hard to imagine the Maccabean Daniel would have wanted to associate himself with the theology of Daniel 2–6.

Consider, by way of illustration, ch. 2’s central message.

God alone knows the future;

God alone can reveal it to people;

and the knowledge God gives his people is ‘certain’ (2.10–11, 27–28, 45).

They ‘do not reside with flesh and blood’, and they cannot, therefore, help their followers.

Daniel was, in the words of H. H. Rowley, ‘a man with an imperfect knowledge of past history and exaggerated hopes for the future’ (Rowley 1959:180–182).

Indeed, Daniel was in exactly the same boat as ch. 2’s wise men!

Like the gods of Babylon, his deity was at best remote and inaccessible, and at worst powerless.

nor had he revealed the future to Daniel (hence the failed prophecies of 11.42ff.).

not least because it would have encouraged his readers to dismiss him as a charlatan.

It’s almost impossible to imagine the Maccabean Daniel would have made a prediction like 11.42–43’s.

On the Maccabean Hypothesis, Daniel was not a ‘prophet’ in the traditional/Biblical sense of the word,

Why, then, would Daniel have sought to begin his career with a prediction as intrinsically unlikely as 11.42–43’s?

It was exactly what the course of history suggested wouldn’t happen!

Antiochus was a spent force.

And Antiochus had only just been told (by the Romans) to leave Egypt well alone (in no uncertain terms).

Whoever arranged the book of Daniel in its final form didn’t view Daniel’s visions/prophecies in the same way as advocates of the Maccabean Hypothesis do.

it goes hand in hand with a particular interpretation of Daniel’s prophecies.

And, if Daniel’s visions reach their climax in the days of the Maccabees (and ipso facto the Greeks),...

Below, I’ll outline just two of them.

Daniel’s schema isn’t merely a list of empires compiled for the sake of historiography.

It’s a depiction of the major influences on Judah’s history over the years—...

The Medes never functioned as Judah’s overlords and had little if any impact on life in ancient Israel (which is why they’re barely mentioned in the OT).

as many advocates of the Maccabean Hypothesis acknowledge (e.g., Lucas 1989:192).

Every time the Median empire is mentioned in the book of Daniel, it is mentioned in the context of Medo-Persia...

And the notion of an independent Median empire would (apparently) have been equally foreign to the Maccabean Daniel’s contemporaries,

But for a Medo-Persian empire to be headed up by a Mede is hardly an unusual fact in need of explanation.

not least because three verses before Darius is installed in Babylon, the Medo-Persians are said to conquer it,

In any case, the flow of chs. 5–6 leaves little room for an independent Median empire to arise.

In 5.28, Babylon falls to the army of a two-pronged alliance—...

In sum, then, the notion of an independent Median empire is quite foreign to the text of Daniel.

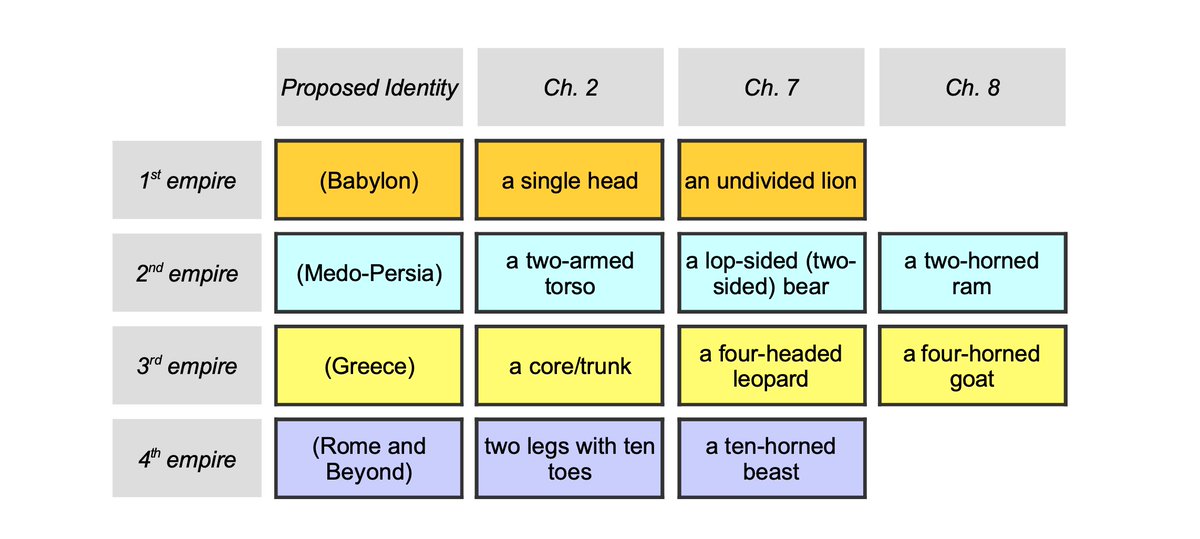

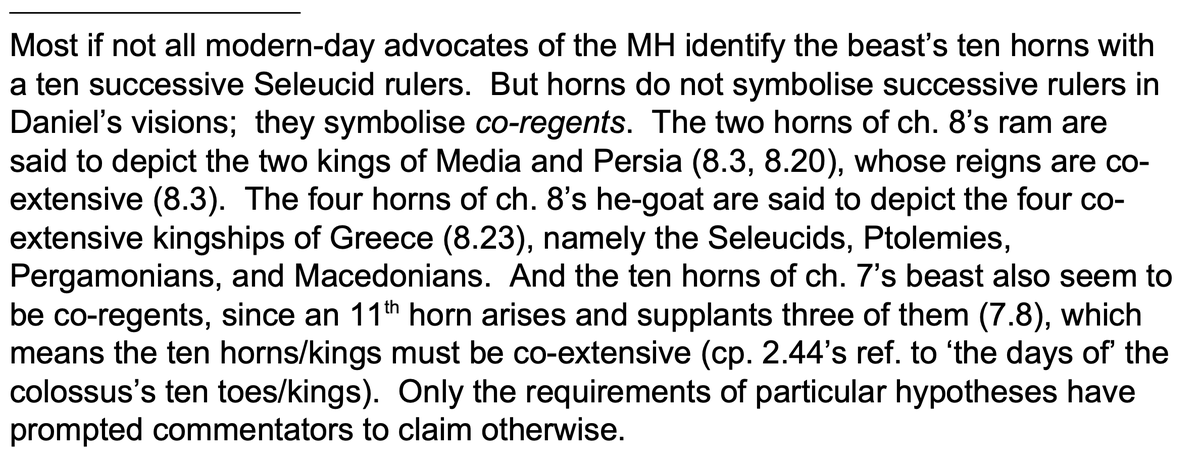

The two-armed torso is aligned with the two-sided bear and the two-horned ram.

The four-headed leopard is aligned with the four-horned goat.

And the ten-toed feet is aligned with the ten-horned beast.

And the leopard with wings on its back resonates with the Greek goat which charges into the ANE with such speed its feet don’t touch the ground.

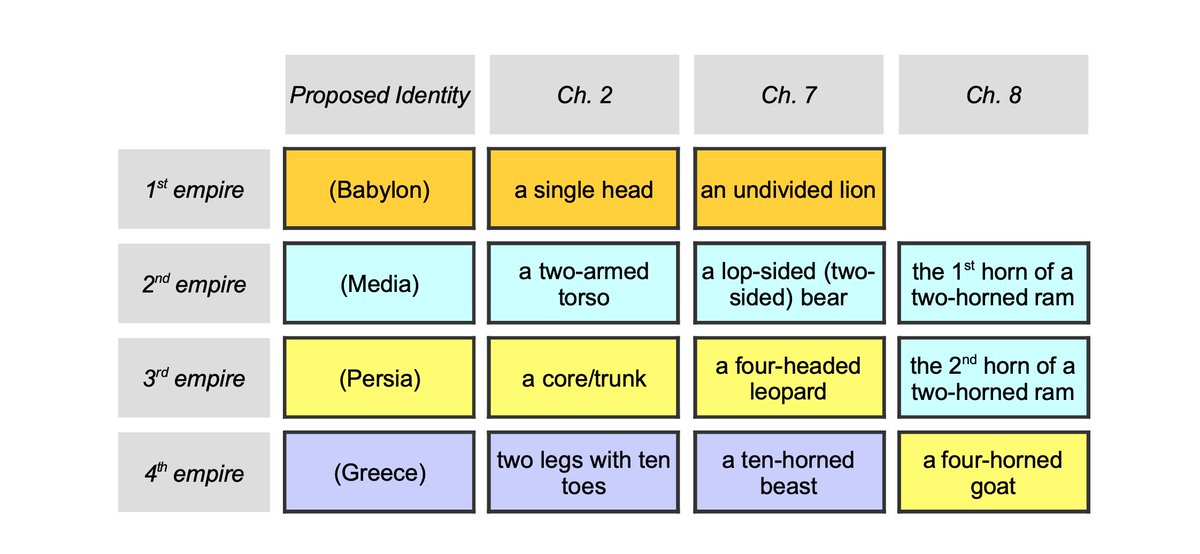

The two-sided bear is no longer aligned with the two-horned ram.

The four-headed leopard is no longer aligned with the four-horned goat.

Daniel’s visions are also out of kilter with what we know of ANE history.

The independent Median empire didn’t consist of two distinct people-groups/parts.

The answer isn’t hard to see.

Since advocates of the Maccabean Hypothesis identify Daniel’s 4th empire with Greece, they have been forced to treat what our author treats as a single empire (Medo-Persia) as two independent empires (Media and Persia),

The lop-sided bear has ended up aligned not with the lop-sidedly-horned (Medo-Persian) ram, but with the first of its horns.

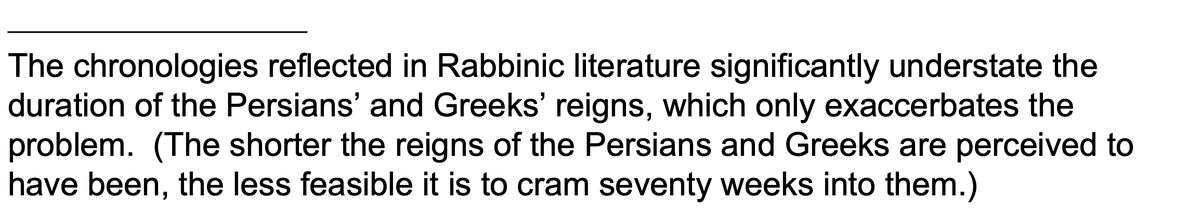

Equally important to note is how Daniel’s seventy weeks relate to these issues.

And when Daniel’s ‘seventy weeks’ (490 years) can’t be accommodated prior to Antiochus’s fall, it is either because Daniel miscalculated (Montgomery 1927:393)...

Of course, all hypotheses have their outliers, which their advocates must somehow explain (if they can). The issue is how often such explanations need to be proffered.

As such, the Maccabean Hypothesis seems practically unfalsifiable,...

It simply begins with a different presupposition.

The Maccabean Hypothesis strikes me as unsatisfactory in at least four important respects.

It fails to explain Daniel’s status.