This is a great article, thank you @2kufic. Despite the rejection of Tabbaa by later scholars, I actually think there is something he seems to've picked up on which most other authors have not. It is not just the script that changes, the spelling and content change too.

https://twitter.com/2kufic/status/1296015949460643841

Anyone who is familiar with Kufic manuscripts will know that it attempts to strictly adhere to the Uthmanic rasm -- the standard consonantal skeleton which all early manuscripts adhere to. Interest in displaying the details of the Quranic reading traditions was subordinate.

Red dots were frequently used to display the reading tradition associated with the manuscript but: they often do not have a system recognisable as a canonical reading. The famous canonical readers who get canonized in the 4th century only show up sometimes and marginally.

The red dots are also not particularly effective at helping the student to read the Quran. They are very useful if you already have a general sense of how you should be reciting, but it lacks the requisite details for the specificities of tajwīd that we see in modern prints today

Moreover, the manuscripts make absolutely *no* concessions to the reading in terms of the rasm. If a reading does not agree with the rasm, the rasm will *not* be changed under any circumstance.

This totally changes in the 10th century when manuscripts shift to cursive scripts.

This totally changes in the 10th century when manuscripts shift to cursive scripts.

Ibn al-Bawwāb's Quran, besides being one of the most impressive pieces of cursive calligraphy ever made, is more than that: it is a *transcription* of al-Dūrī's transmission of ʾAbū ʿAmr's reading. It is not a muṣḥaf in the Uthmanic rasm tradition, it completely let's go of it.

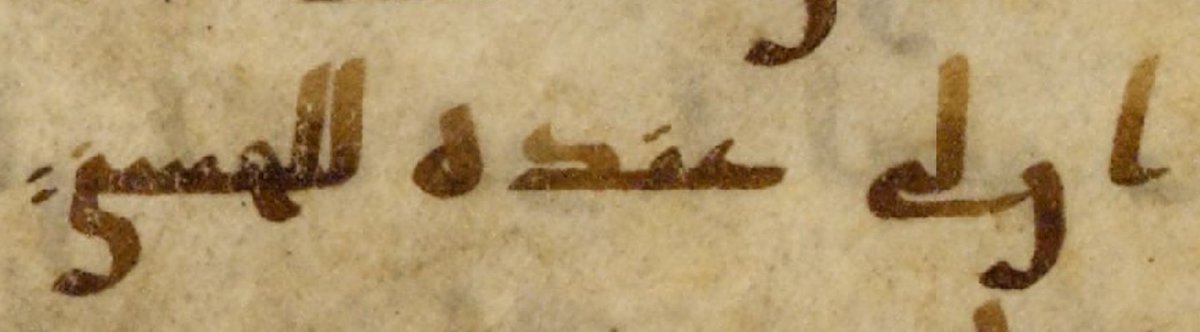

This is can be shown by Q19:19. ʾAbū ʿAmr ignores the standard rasm in Q19:19 لاهب and reads li-yahaba 'so that he give', rather than the more straightforward reading li-ʾahaba 'so that I give'. Kufic manuscripts don't write ليهب and rather use red ink to modify the rasm.

Once we look at the Ibn al-Bawwāb Quran, and qurans of its kind, we see that scribes have absolutely zero problem with deviating from the Uthmanic rasm. There is a much larger focus on precise and accurate representation of the reading tradition, at the cost of the Uthmanic rasm.

Other things in which the text is classicized is that the ʾalif for ā is *always* written, while this is comparatively rare in Uthmanic manuscripts. Also the typical orthographic idiosyncrasies that mark the 'fingerpint' of the Uthmanic tradition are lost.

Thus, these manuscripts are no longer copies of a written exemplar, ultimately stemming back to the time of Uthman, but are simply transcriptions of an oral recitation.

This clearly marks a massive shift in focus from the written to the oral in Quranic transmission.

This clearly marks a massive shift in focus from the written to the oral in Quranic transmission.

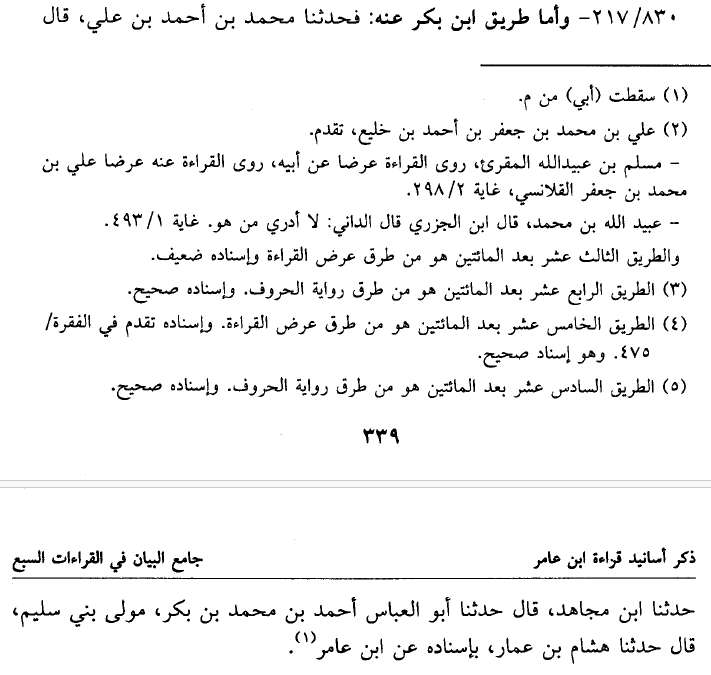

It is certainly not a coincidence that this newfound focus on the oral tradition at the expense of the written tradition happens in the 10th century, the century in which also Ibn Mujāhid canonizes the 7 canonical readers of the Quran. For the first time there was an oral canon.

While the Maghreb also undergoes a clear evolution towards stronger clarification of reading traditions, and the script evolves as well. They remain quite distinct. The Maghrebi scribal tradition continues to view the rasm as inviolable, and continue the Uthmanic tradition.

While more and more specialized signs are developed to more carefully represent the Quranic readings (or more precisely almost exclusively the readings of Warš and Qālūn from Nāfiʿ), they continue to be written in separate colours and thus remain distinct from the rasm.

I would also argue that what we consider the Maghrebi script is a much more natural evolution from the Kufic script than a clear break with that tradition that we find in the eastern cursive scripts. Still, the Maghrebi tradition does evolve around this time too, just differently

So, there really is a point to Tabbaa's ideological explanation. He's right that the change of script coincides with the canonization of the readings, and the changes we find in orthography are deeply concerned with the readings and not at all with the rasm of the kufic tradition

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more stuff like it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh