I recently did a thread on the Yemenite Judeo-Arabic reading tradition of Saadya Gaon's Hebrew Bible translation. It revealed a consistent linguistic system, separate from Classical Arabic with several Hebraisms... let's look at the 10 Commandments today!

https://twitter.com/PhDniX/status/1293230397858471936

Again I will be looking BOTH at the transcription and the way it is actually read, and contrast when there are differences.

I won't comment on striking features that I commented on already in last thread!

I won't comment on striking features that I commented on already in last thread!

ʔanā ʔaḷḷāh rabb-ak ʔallaḏī ʔaḫrajt-ak min balad miṣr min bayt al-ʕabūdiyyah

"I am God, your Lord, who brought you from the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage."

- Note the 1sg. suffix conjugation is just -t, like modern dialects, followed by 2sg.m. -ak.

"I am God, your Lord, who brought you from the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage."

- Note the 1sg. suffix conjugation is just -t, like modern dialects, followed by 2sg.m. -ak.

lā yakūn l-ak maʕbūd ʔuxar min dūn- ī.

“You shall not have anyone worshiped other than me”

- The transcription reads ʔuxar or even ʔuxxar, the plural of ʔāxar 'other'. ʔāxar seems more natural to me here, and this is what the reciter reads. Identical consonantal text.

“You shall not have anyone worshiped other than me”

- The transcription reads ʔuxar or even ʔuxxar, the plural of ʔāxar 'other'. ʔāxar seems more natural to me here, and this is what the reciter reads. Identical consonantal text.

The translation deviates from the Hebrew here:

lo yihwɛ lḵå ʾɛ̆lohim ʾăḥerim ʿal-pånåy "you will not have other gods before me", for plural "gods" the translation has the singular maʕbūd 'worshiped', perhaps the original Hebrew plurals triggered the ʔuxar instead of ʔāxar.

lo yihwɛ lḵå ʾɛ̆lohim ʾăḥerim ʿal-pånåy "you will not have other gods before me", for plural "gods" the translation has the singular maʕbūd 'worshiped', perhaps the original Hebrew plurals triggered the ʔuxar instead of ʔāxar.

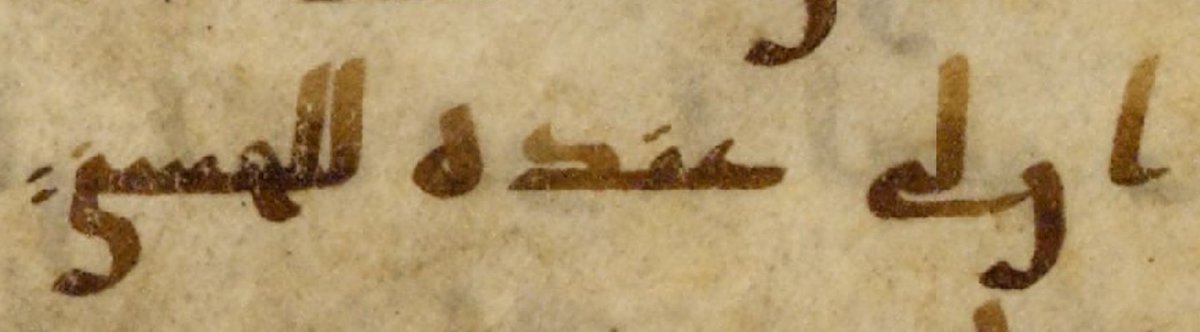

Wa-lā taṣnaʕ l-ak faslā wa-lā šabhā mimmā fī s-samā fī l-ʕilu u-mimmā fī l-ʔarḍ fī s-sifl u-mimmā fī l-mā ʔallaḏī tiḥt al-ʔarḍ

“And don’t make for yourself something lowly, nor a likeness of something in the heaven above or the earth below or the water under the earth.”

“And don’t make for yourself something lowly, nor a likeness of something in the heaven above or the earth below or the water under the earth.”

- The transcription reads fī l-ʕilu "in the above" (cf. Classical al-ʕalu) and fī s-sifl "in the below" (cf. Classical as-sufl), the recited read fī l-ʕilā and fī s-sifāl which don't fit the consonantal skeleton here.

- Note that words like as-samā lack the final hamzah. This is not too surprising, all hamzah's are missing, but in Quranic Arabic this is one of the few hamzahs that are retained.

- Note the high vowel in tiḥt 'below' rather than Classical taḥta.

- Note the high vowel in tiḥt 'below' rather than Classical taḥta.

lā tasjud lahā wa-lā taʕbid-hā

“Do not prostrate to it, nor worship it”

-Transcription has the more classical lā tasjud, but the reciter recites: lā tisjid.

“Do not prostrate to it, nor worship it”

-Transcription has the more classical lā tasjud, but the reciter recites: lā tisjid.

La-ʔannī ʔaḷḷāh rabb-ak aṭ-ṭāyig al-muʕāgib, muṭālib bi-ḏunūb al-ʔābā maʕ al-banīn wa-ṯ-ṯawāliṯ wa-r-rawābiʕ li-šāniy-ay

"For I, God, your lord, the able punisher, hold accountable for the sins of the father: the children, and the 3rd and 4th (generation) of my haters”

"For I, God, your lord, the able punisher, hold accountable for the sins of the father: the children, and the 3rd and 4th (generation) of my haters”

- Again a striking deviation from the Hebrew; also in this case seemingly scrubbing away implied polytheism. Aṭ-ṭāyig, al-muʕāqib "the able, the punisher" stands in the place of "am a jealous God who".

- šāniy-ay seems to be another Hebraism.

The typical Classical form is šāniʾ-ī-ya.

The sound construct plural ending -ī- + -ya seems to be replaced by the Hebrew (!) construct plural + 1sg. which is a portmanteau morpheme -ay

We will see this again in the last verse.

The typical Classical form is šāniʾ-ī-ya.

The sound construct plural ending -ī- + -ya seems to be replaced by the Hebrew (!) construct plural + 1sg. which is a portmanteau morpheme -ay

We will see this again in the last verse.

The reciter does something very odd with šāniy-ay; sounds to me like he says šaʔnī, which doesn't make much sense to me. Happy to hear suggestions what is going on with that.

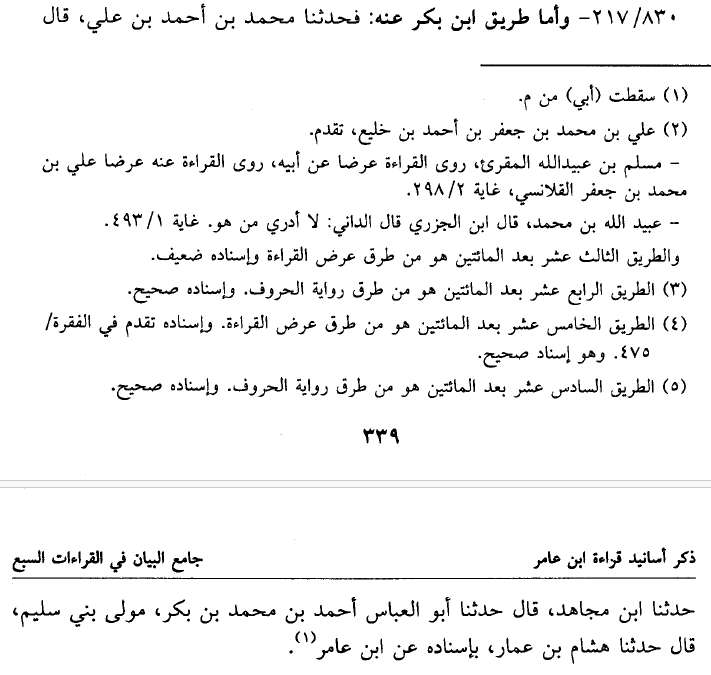

U-mjāzī bi-l-ʔiḥsān li-ʔilūf min mḥibb-ay wa-ḥāf(i)ḍī waṣāyā-y.

"And (I am) a repayer with kindness to thousands (of generations) from those that love me and are keepers of my commandments."

-The u of mujāzī and mḥibb-ay have been reduced, written as shwa (syncope, or ə?)

"And (I am) a repayer with kindness to thousands (of generations) from those that love me and are keepers of my commandments."

-The u of mujāzī and mḥibb-ay have been reduced, written as shwa (syncope, or ə?)

-The reciter has a variant here. Not mujāzī "repaying with kidness", but ṣāniʕ al-ʔiḥsān "the maker of kindness"

- mḥibb-ay in Classical would be muḥibb-ī-ya; again the Hebrew plural+1sg portmanteau morpheme -ay is used instead. This time also heard in recitation.

- mḥibb-ay in Classical would be muḥibb-ī-ya; again the Hebrew plural+1sg portmanteau morpheme -ay is used instead. This time also heard in recitation.

- Finally, the vocalisation suggests syncope in wa-ḥāfḍī waṣāyā-y "and the keepers of my commandments" (rather than Classical ḥāfiẓī waṣāyā-ya). Sounds to me like the reciter pronounces the vowel.

That's the end of the text and the end of my observations!

That's the end of the text and the end of my observations!

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more stuff like it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh