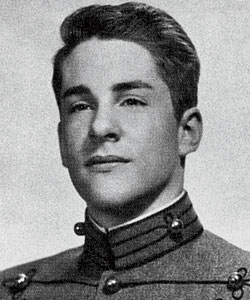

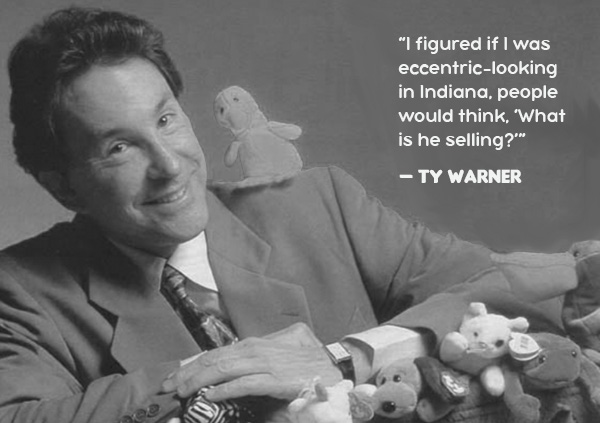

Ty had a talent for getting meetings with top toy buyers by building intrigue. One of the ways he did that was by showing up for sales calls in a white Rolls Royce, wearing a fur coat.

His supervisor called him "the best salesman I ever met."

When Dakin found out, Ty was fired.

For a long time, Ty didn't know what to do.

He went to Italy.

And he kept working on his pet project.

He thought there was something in it, even if everyone he showed the toys thought they looked like "roadkill."

"They looked real because they moved," Ty commented.

(Ed — really...?)

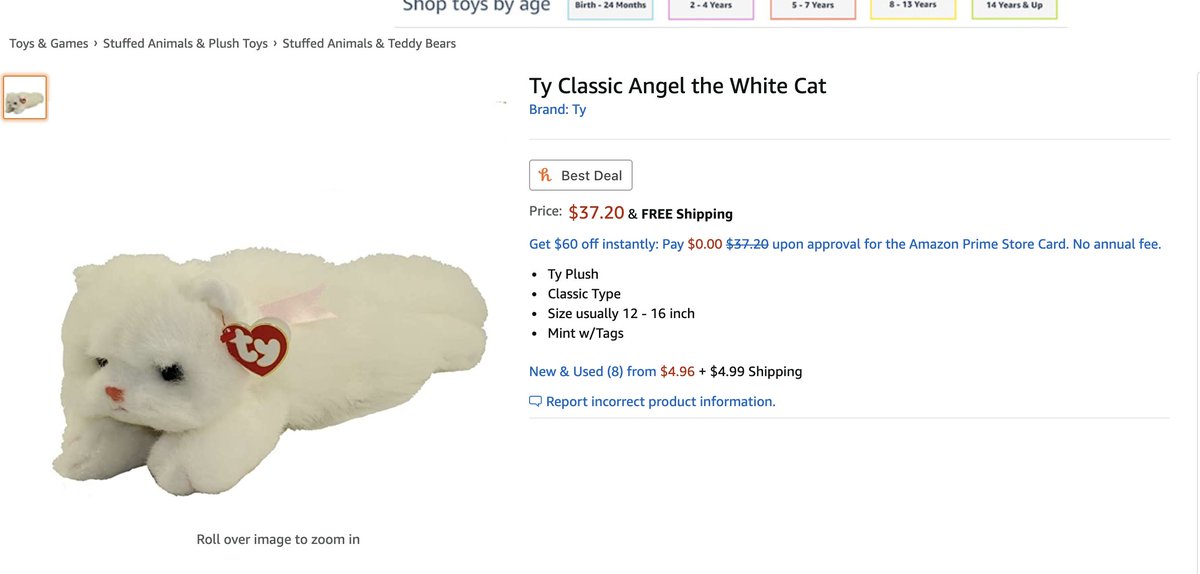

Ty wanted customers to feel as if the toys were always running out.

Yet again, perceived scarcity drove impulse purchasing.

Piggybacking off the rise of the internet, and secondhand marketplaces like Ebay, Beanie Babies saw their prices skyrocket after "retirement."

A $5 would sell for $10, $100, $300. Some sold as high as $13K.

A 3,000x mark-up.

As Beanie Babies achieved eye-watering values, a spate of toy-related crimes erupted.

In late 1999, the year after Ty Inc. brought in $1B in sales, the bubble popped.

Ty Inc. released a new set of Beanie characters and this time? Nothing.

No frenzied lines. No runs on local stories. No ludicrous mark-ups. No cashiers held at gunpoint.

Sellers flooded Ebay with their goods. Prices spiraled.

Ty scrambled, declaring that *all* Beanie Babies would go out of production in 1999. He'd hoped to spark a run.

Nothing worked. The spell had been broken.

There's both a lesson and a warning in the chaos Ty created. The tactics Ty used to incentivize buyers are a case-study in building hype. But founders must also be wary of the world they create.

And if you'd like to read more of my writing, please subscribe to my newsletter The Generalist. I'd love to welcome you aboard.

readthegeneralist.com