First time that the pre-Islamic record gives evidence of fully functioning Tanwīn! Even though the use of full ʾiʿrāb + tanwīn becomes THE prime feature for high "Classical" speech in Arabic, up until we would only find it in Islamic Era Classical Arabic.

Forms of Old Arabic in the pre-Islamic period consistently lack this feature. It is absent Safaitic, Hismaic and Nabataean Arabic.

Some people, like Jonathan Owens, even doubted that it was a genuine feature at all, and it was maybe made up by the Arab Grammarians.

Some people, like Jonathan Owens, even doubted that it was a genuine feature at all, and it was maybe made up by the Arab Grammarians.

Based on historical linguistic evidence, there was reason to believe the feature was archaic, even though it only showed up in late sources, as me and @Safaitic have argued in our reply to Jonathan Owens here:

academia.edu/28267720/Al_Ja…

Still, it is good to now have evidence for it!

academia.edu/28267720/Al_Ja…

Still, it is good to now have evidence for it!

Considering how early and how marginal it is, though, it still remains a real mystery how in the Islamic period the variety with full ʾiʿrāb and tanwīn gained such incredible prestige that the medieval grammarians simply refused to acknowledge any other form of Arabic existed.

It is clear from Arabic written in non-Arabic script, that already in the first and second centuries, the period before and up until the time of the earliest grammarians the absence of ʾiʿrāb and tanwīn was the norm... but if you would read grammarians you would never know.

This demonstrable collective willful blindness of the grammarians forces us to be very careful about the data they generate. As a result we cannot assume that all the written Arabic produced in the Islamic period had ʾiʿrāb+tanwīn, as there is clear evidence to suggest otherwise.

For this reason, me and @phillipwstokes have looked closely at the oldest layer of the Quran, the Quranic Consonantal Text, looking at orthographic and rhyme patterns and concluded that even Quranic Arabic probably lacked full ʾiʿrāb+tanwīn

academia.edu/37481811/Case_…

academia.edu/37481811/Case_…

When the "Classical system" of ʾiʿrāb+tanwīn developed its now ubiquitous prestige, the Quran could of course not stay behind, and this system was imported into its recitation.

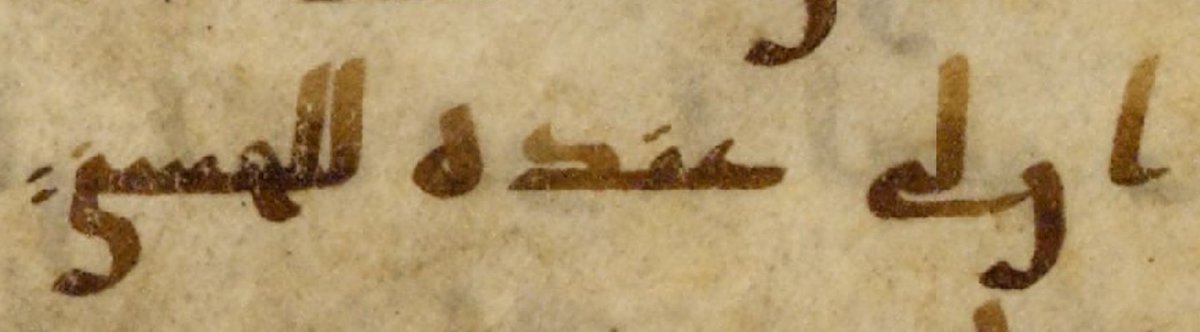

A trace of that transition can probably be seen in the way early manuscripts are vocalised...

A trace of that transition can probably be seen in the way early manuscripts are vocalised...

When vowel signs, by means of red dots, were invented they were not applied to mark all vowels. The vocalisers are uninterested in the vowels on the inside of a word, which suggests they considered those self-evident. It was used almost exclusively to mark ʾiʿrāb+tanwīn.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh