Some thoughts on the PRC’s growing IRBM force:

I recently pointed out what I thought was the biggest news in the recently-released 2020 China Military Power report: an apparent more-than-doubling of the PLA Rocket Force’s DF-26 IRBM inventory.

I recently pointed out what I thought was the biggest news in the recently-released 2020 China Military Power report: an apparent more-than-doubling of the PLA Rocket Force’s DF-26 IRBM inventory.

https://twitter.com/tshugart3/status/1300859315398426624

This growth to IRBM launchers is a continuation of previous trends: the 2018 report had listed "16-30" launchers, then 80 in the 2019 report, and now 200 in this year's report. iiss.org/blogs/military…

I said in my commentary that, if this growth in capability is real, it could present a more significant challenge to the American way of war in the Western Pacific.

I'd like to expound on that a bit more.

I'd like to expound on that a bit more.

https://twitter.com/tshugart3/status/1300860786680553472

The report lists "200+" as the number of likely missiles available, given 200 launchers. We know from Chinese TV footage that DF-26 units practice reloading missiles, and that the missiles have different warhead types that are swappable.

armscontrolwonk.com/archive/120940…

armscontrolwonk.com/archive/120940…

Thus, if each launcher had only one reload missile available (and there may be more than that), this would mean an IRBM force of more than 400 DF-26's, all configurable to anti-ship or land-attack missions (including nuclear, though that's not what really concerns me).

Some observers may not be too concerned about the deployment of a single such weapon system, but the scale of this change matters: going from dozens of missiles to hundreds is a quantitative change big enough to drive qualitative effects, esp. given the longer range of the DF-26.

First, at sea the number of missiles could broaden the PLARF's antiship mission from a "carrier-killer" focus to a generic "ship-killer" mission. China itself describes the DF-26 as capable against medium *and* large ships. globaltimes.cn/content/119694…

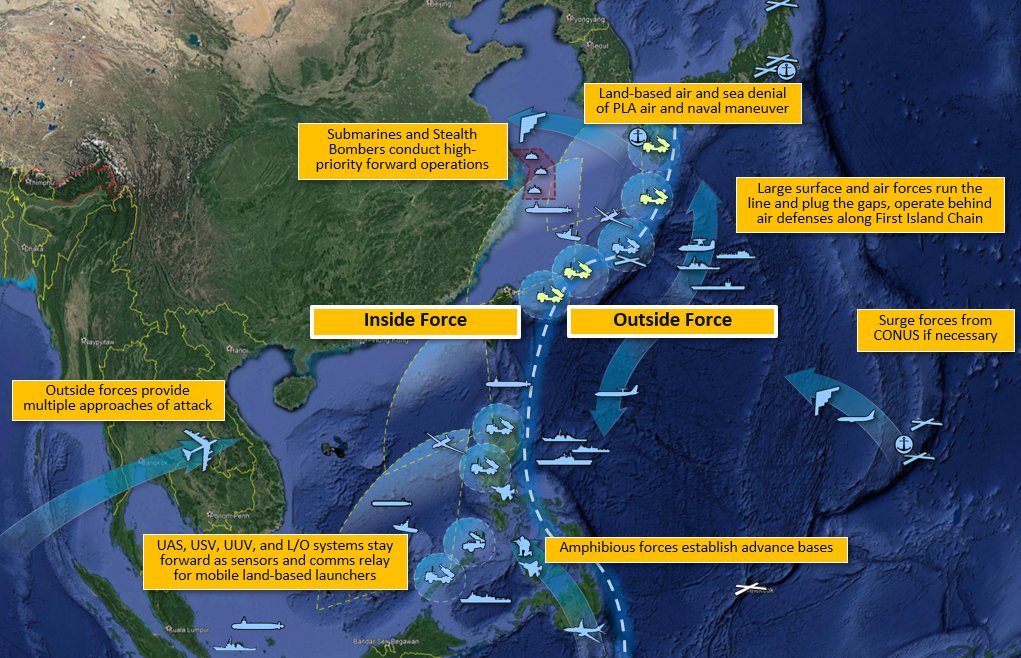

This change could matter in how it intersects with the USN's distributed lethality construct: an effort to distribute offensive combat power - partly given the threat of what were dozens of DF-21D ASBMs - away from carriers to smaller, more numerous ships. usni.org/magazines/proc…

With a much greater number of available ASBMs, these smaller warships - LCSs, DDGs, and especially logistics ships - could become "ASBM-worthy" as well. businessinsider.com/in-war-china-u…

The story is no better for USAF tactical aircraft & bombers based in-theater. With smaller numbers of long-range missiles, air operations might be possible from Guam or dispersed locations. But with hundreds of missiles available, this seems unlikely IMO. defensenews.com/digital-show-d…

While some might point to the heavy bombers as an answer to providing land & maritime strike (I agree, to a point), one wonders how long they would survive - or be able to find targets - without effective tac air support available from local airfields. reuters.com/investigates/s…

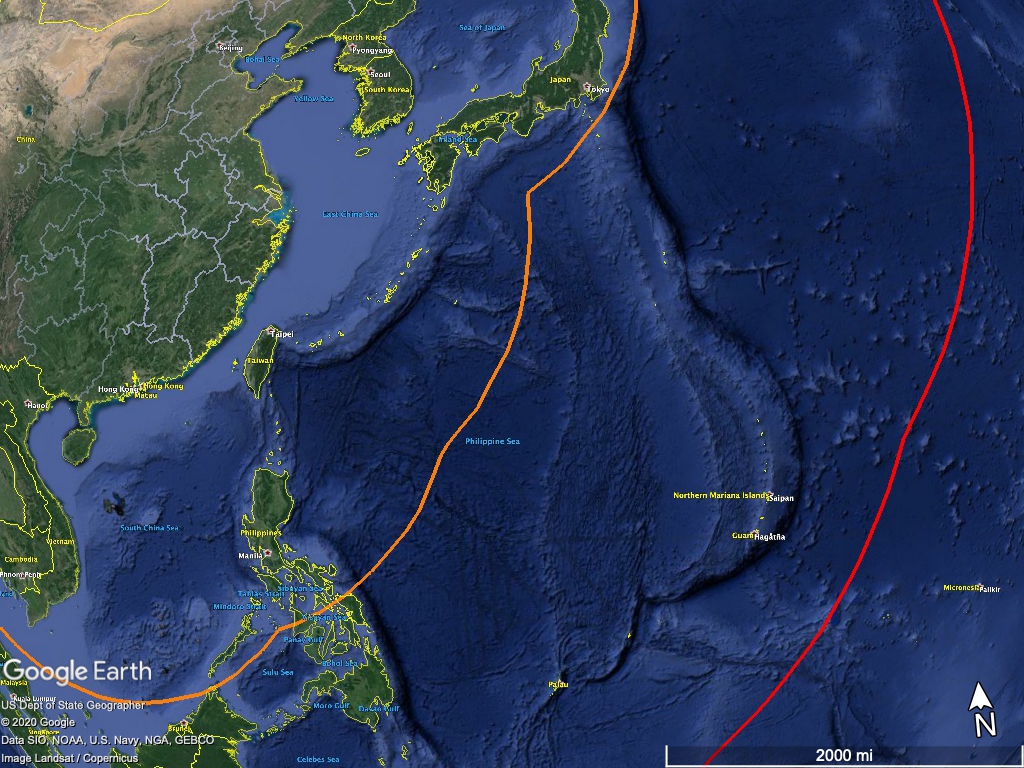

The next way the DF-26 force matters is through its much greater range, in particular the specific additional areas that it can strike. In the Philippine Sea, areas of relative sanctuary beyond the range of the DF-21 (1500km+) lie well within range of the DF-26 (4000km).

These areas have mattered in how US defense thinkers looked at the regional A2/AD challenge, positing the ability to operate forces reasonably safely outside the 1st island chain as a means to enable operations closer-in to defend our interests & allies. cimsec.org/tightening-the…

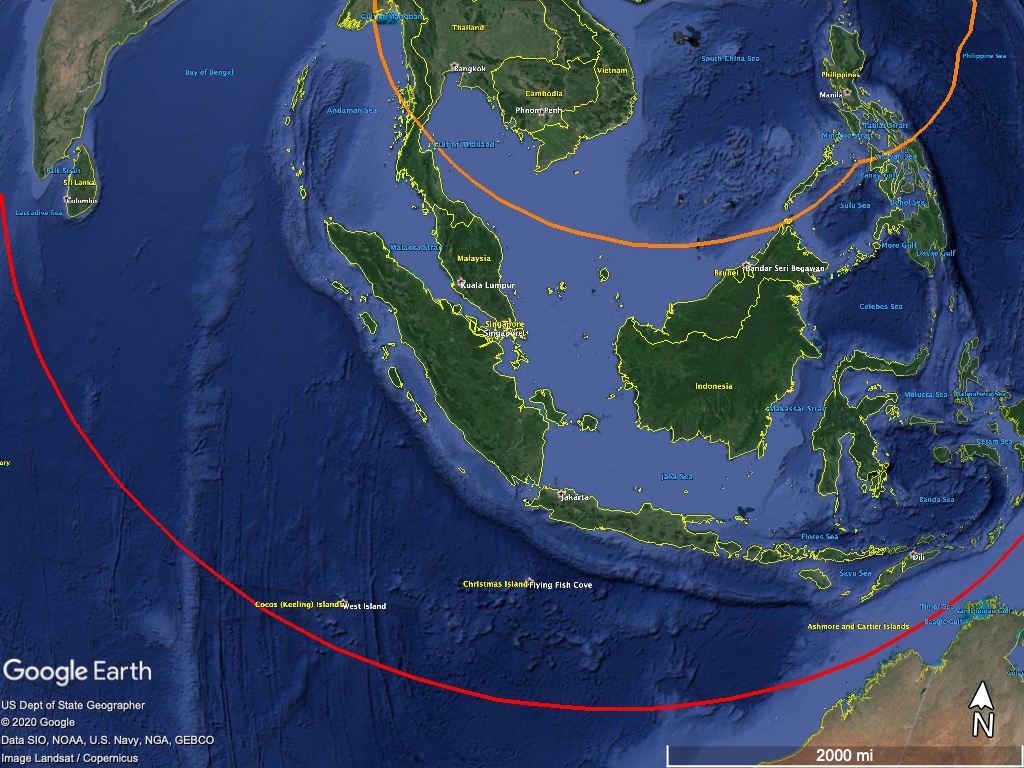

Further southwest, PRC thinkers have obsessed over the "Malacca dilemma", with China's vital imports vulnerable to chokepoint interception en route. With large numbers of DF-26s, the PLA may now have the ability to strike US/allied warships attempting to maintain such a blockade.

The same could now be true in the vital sea lanes leading from the Mid East to Asia and Europe, with coverage extending from PLARF bases in western China.

Now, some commentators have been incredulous that the PLA's IRBM force could have grown so quickly given the scale of expansion that would be required.

forbes.com/sites/davidaxe…

forbes.com/sites/davidaxe…

From my perspective, I doubt that the DoD would just make up these numbers, and TELs are not like mysterious underground WMD sites or an adversary's strategic intentions. They are distinct physical objects that can be counted from space.

Perhaps they're not fully integrated into effective combat units yet; but if that is the case it's still just a matter of time.

Other observers were already tracking an unprecedented expansion of the PLARF; seems like a continuation of that trend to me. popsci.com/story/blog-eas…

Other observers were already tracking an unprecedented expansion of the PLARF; seems like a continuation of that trend to me. popsci.com/story/blog-eas…

Some observers have also doubted China's ASBMs have the ability to strike moving targets at sea. But for the 2nd year in a row the report states flat out that the DF-26 "is capable" of conducting strikes against naval targets. This is pretty strong language for an intel report.

And for the 2nd year in a row China has launched them into the South China Sea. globaltimes.cn/content/119694…

To be sure, as has been discussed by USN's leadership before, the range arcs of the PLA's ASBMs are not impenetrable, nor is the PLARF its first "A2/AD" challenge.

But IMO it's hard to deny a substantially increased level of risk, over a much larger area.

businessinsider.com/navy-can-fight…

But IMO it's hard to deny a substantially increased level of risk, over a much larger area.

businessinsider.com/navy-can-fight…

I'm still working on my thoughts about what to do about all of this, as to be sure I don't think there are any easy - or even very palatable - answers.

But my sense is that the trajectory that we are on as a nation is not keeping pace with the threat to our interests and allies.

But my sense is that the trajectory that we are on as a nation is not keeping pace with the threat to our interests and allies.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh