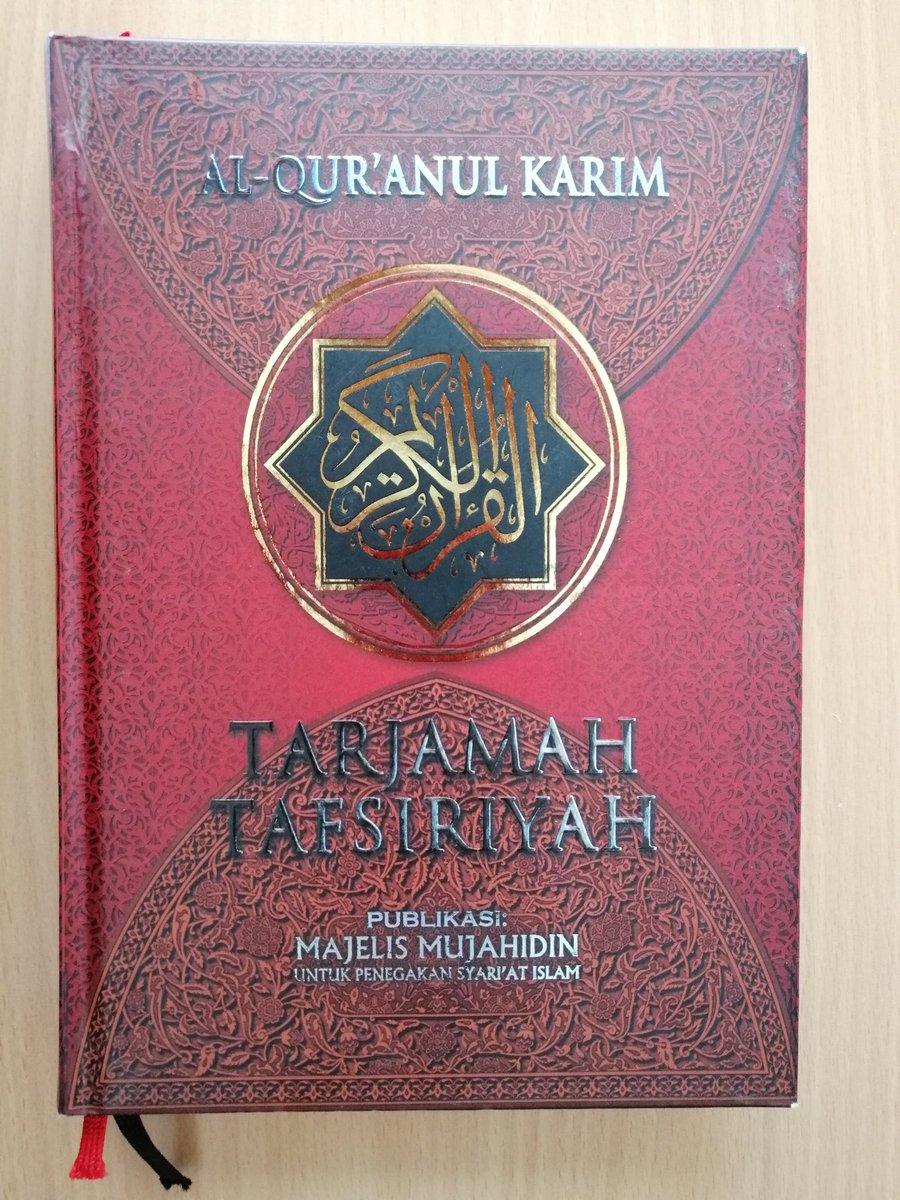

This is not a translation, it is a counter-translation. Muhammad Thalib’s

“exegetical translation”, first published in 2011, is a direct attack on the Indonesian government. #qurantranslationoftheweek 🌏🇮🇩

“exegetical translation”, first published in 2011, is a direct attack on the Indonesian government. #qurantranslationoftheweek 🌏🇮🇩

The Indonesian government publishes its own Qur’an translation, which

dominates the Indonesian market (see gloqur.uni-freiburg.de/blog/qur2019an…).

dominates the Indonesian market (see gloqur.uni-freiburg.de/blog/qur2019an…).

Consequently, criticizing the government translation implies an attack on the authority of the state, as Munirul Ikhwan has shown in his JQS paper on Muhammad Thalib’s translation

(euppublishing.com/doi/full/10.33…).

(euppublishing.com/doi/full/10.33…).

Muhammad Thalib (b. 1948) is the leader of the Majelis Mujahidin Indonesia, an Islamist organization. Indonesian Islamists have a long-standing quarrel with the government ever since the first president, Sukarno,

removed the obligation for Muslims to adhere to the sharia from the draft

constitution in 1945. Majelis Mujahidin Indonesia was founded in 2000, after

democratization, with the aim of reinstating this clause to the constitution.

constitution in 1945. Majelis Mujahidin Indonesia was founded in 2000, after

democratization, with the aim of reinstating this clause to the constitution.

MMI has been seen as connected to al-Qa’ida and other terrorist groups, a

claim that its later leadership, including Muhammad Thalib, protested. Their publishing activities are part of an effort to frame their activities as respectable and scholarly.

claim that its later leadership, including Muhammad Thalib, protested. Their publishing activities are part of an effort to frame their activities as respectable and scholarly.

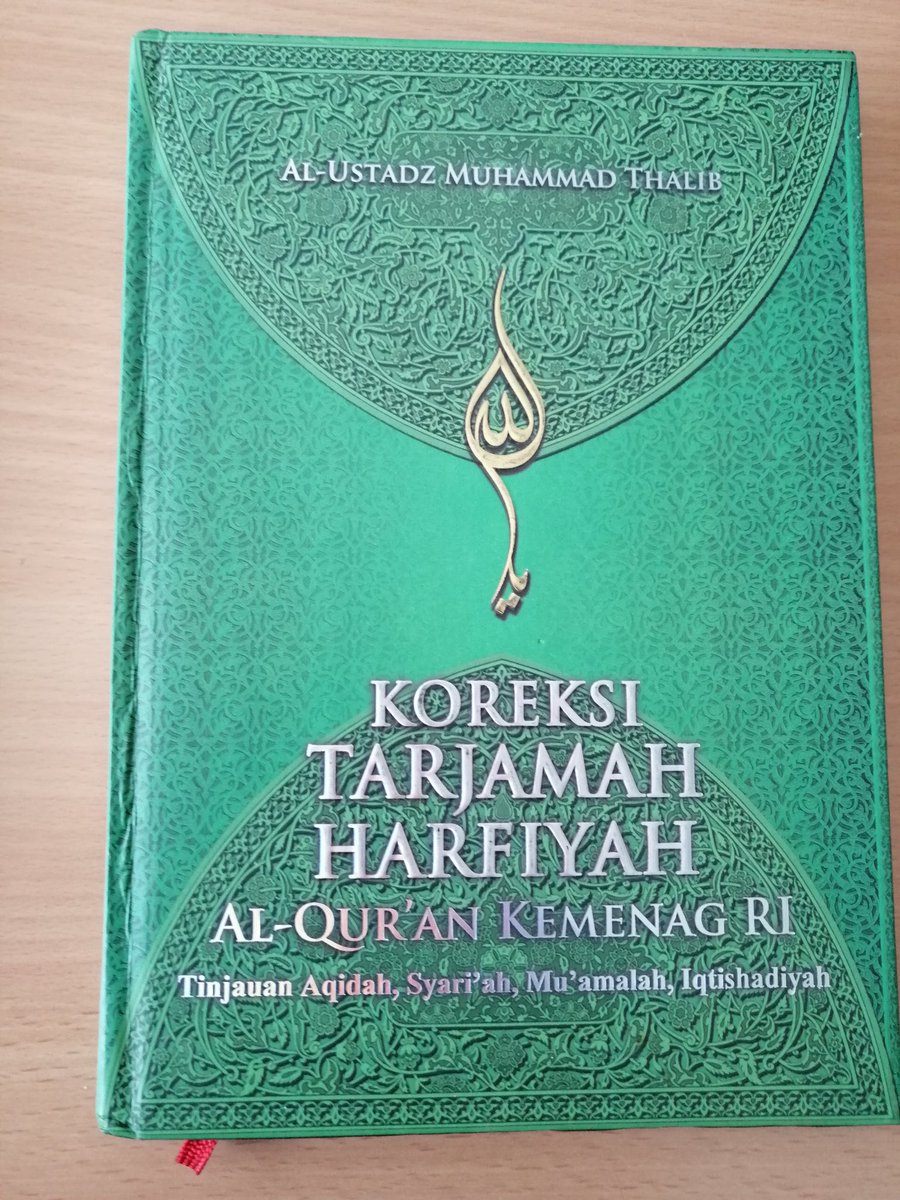

Alongside his “exegetical translation”, Thalib published a “correction of the

literal translation” by the Ministry of Religious Affairs. Listing hundreds of “errors”, he even accused that translation of promoting terrorism by rendering the Qur’anic text literally,

literal translation” by the Ministry of Religious Affairs. Listing hundreds of “errors”, he even accused that translation of promoting terrorism by rendering the Qur’anic text literally,

without the exegetical explanations that he considered indispensable. This is part of a fierce ideological debate in Indonesia on the merits of “literal” (harfiyah) versus “exegetical” (tafsiriyah) translation where it is often Salafis, interestingly, who demand the latter.

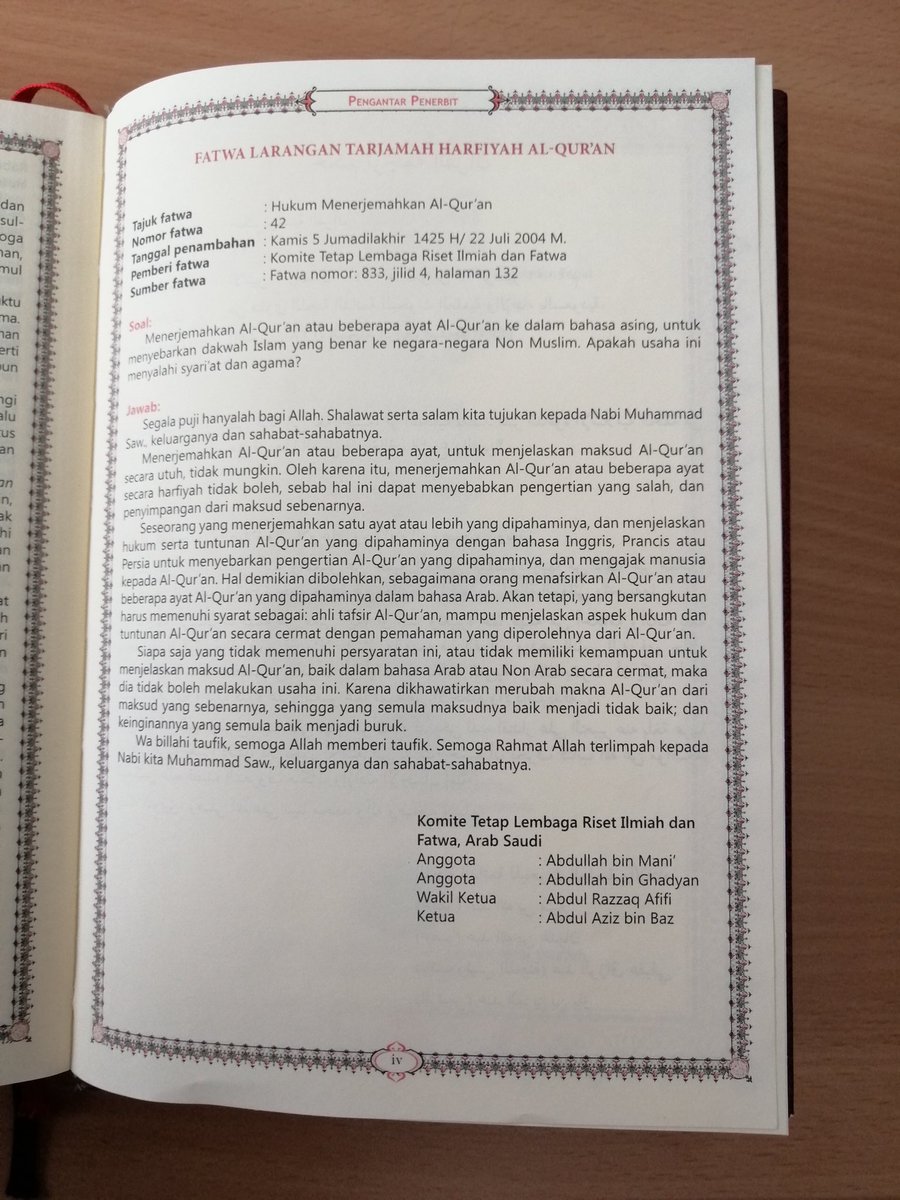

In the extensive introduction to his translation, Thalib even quotes a Saudi

fatwa that prohibits “literal” translations. They invite misunderstandings, he claims, and confuse Muslims. Therefore, translators should always provide the “correct” interpretation of a verse.

fatwa that prohibits “literal” translations. They invite misunderstandings, he claims, and confuse Muslims. Therefore, translators should always provide the “correct” interpretation of a verse.

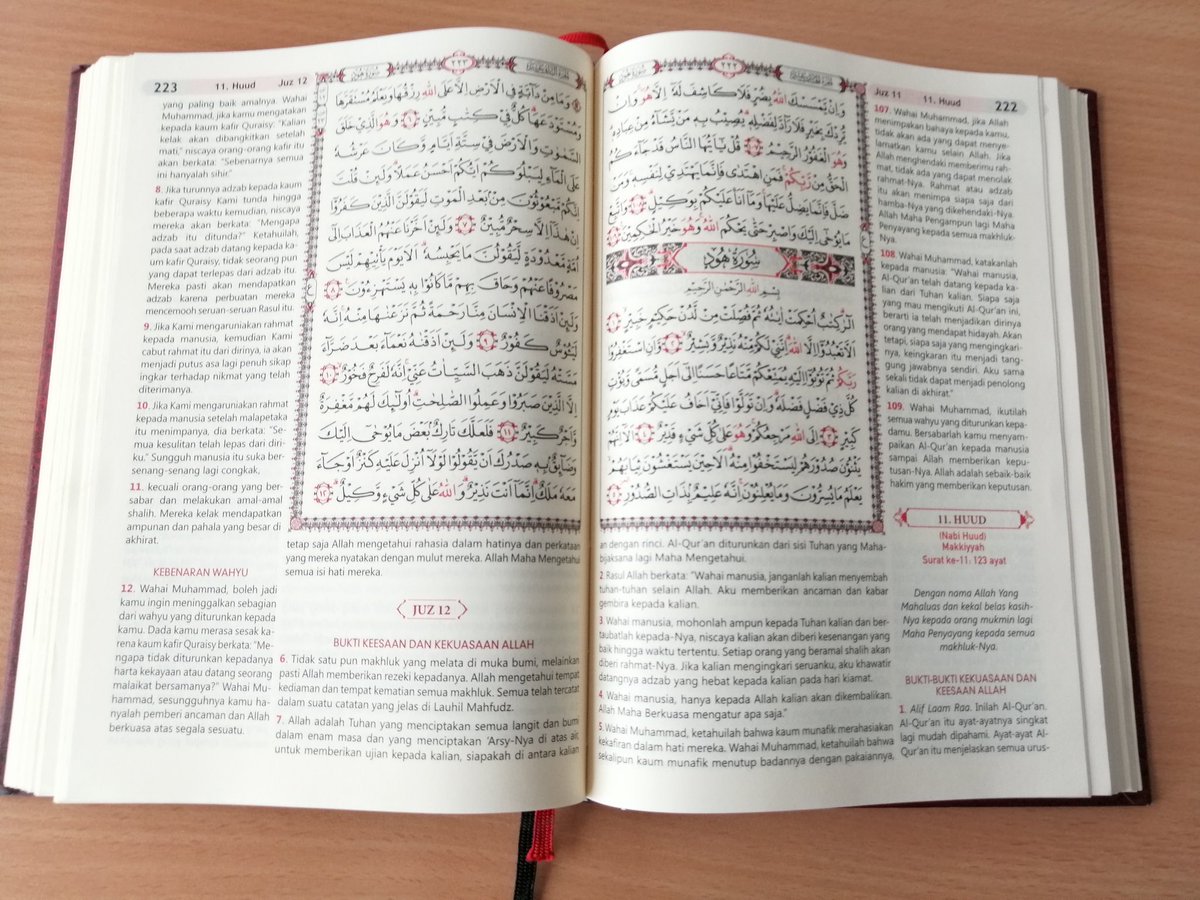

For example, Q 11:108 promises the “felicitous” (alladhīna suʿidū) eternal

paradise, “except what your Lord may wish” (illā mā shāʾ a rabbuka). The

government translation renders this as “except if your Lord wishes (otherwise)” (kecuali jika Tuhanmu menghendaki [yang lain]).

paradise, “except what your Lord may wish” (illā mā shāʾ a rabbuka). The

government translation renders this as “except if your Lord wishes (otherwise)” (kecuali jika Tuhanmu menghendaki [yang lain]).

Muhammad Thalib claims that this leads readers to believe that God acts

according to His whims, without regard for justice. Instead, he says, the verse refers to the fact that for some believers, hellfire might not be eternal.

according to His whims, without regard for justice. Instead, he says, the verse refers to the fact that for some believers, hellfire might not be eternal.

He bases this on the Saudi “al-Tafsīr al-Muyassar” and translates the four

Arabic words as “But there are people who have already completed their term of punishment in hell and then enter paradise according to the will of your Lord.”

Arabic words as “But there are people who have already completed their term of punishment in hell and then enter paradise according to the will of your Lord.”

(Tetapi ada orang-orang yang telah selesai menjalani adzab neraka

kemudian masuk surga sesuai kehendak Tuhanmu.) Thus, Thalib’s translation is extensive and does not closely follow the source text. It also provides an additional interpretive structure by adding headers.

kemudian masuk surga sesuai kehendak Tuhanmu.) Thus, Thalib’s translation is extensive and does not closely follow the source text. It also provides an additional interpretive structure by adding headers.

As Munirul Ikhwan has shown, Thalib frequently blames the Ministry for

glossing over negative portrayals of Judaism. He himself uses his exegetical method of translation in order to promote an exclusivist reading, which is particularly controversial in the Indonesian context

glossing over negative portrayals of Judaism. He himself uses his exegetical method of translation in order to promote an exclusivist reading, which is particularly controversial in the Indonesian context

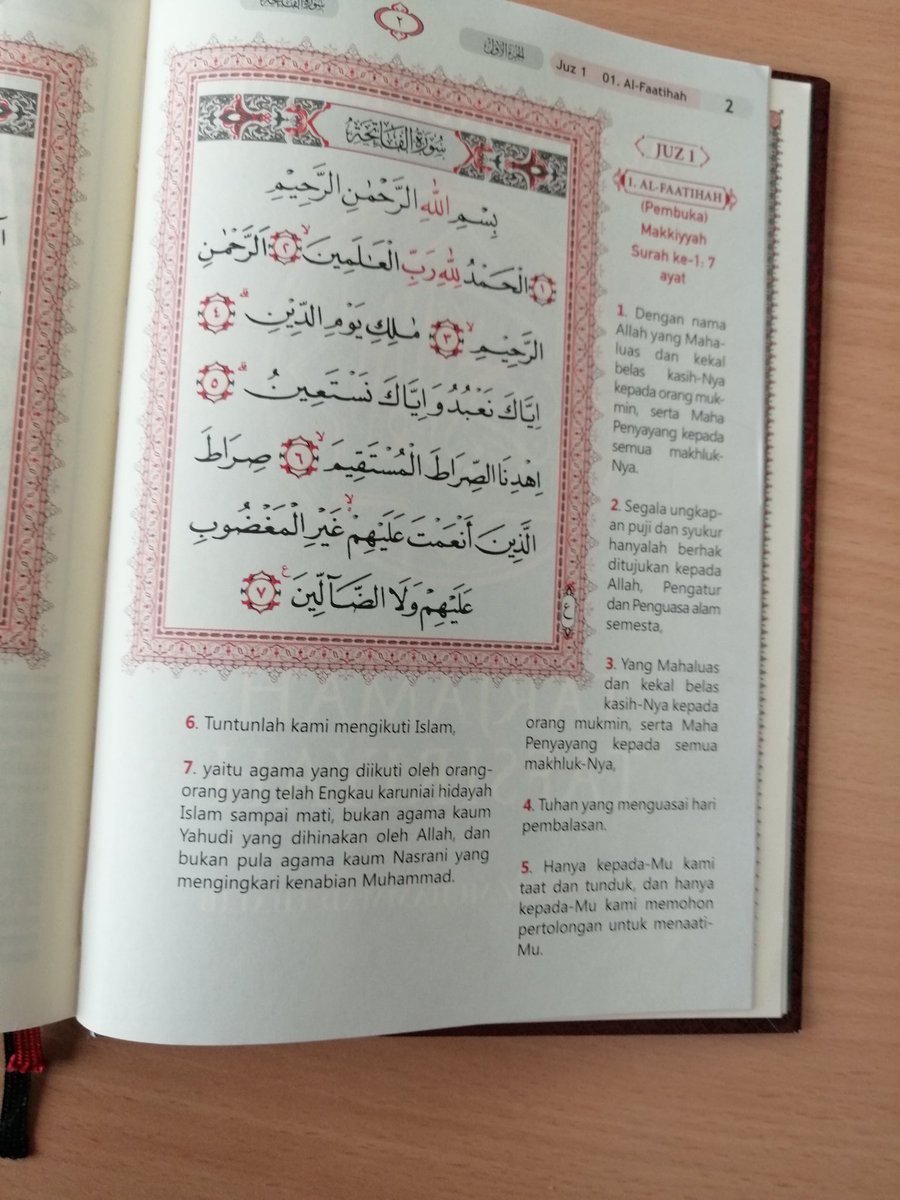

where religious tolerance and pluralism are frequently promoted. For

example, Thalib translates the last two verses of the Fatiha (“Guide us on the

straight path; the path of those whom You have blessed, not those who have

incurred wrath, nor are astray”) as:

example, Thalib translates the last two verses of the Fatiha (“Guide us on the

straight path; the path of those whom You have blessed, not those who have

incurred wrath, nor are astray”) as:

“Guide us towards Islam, that is, the religion followed by those whom You

have blessed with the guidance of Islam before their death, not the religion of the Jews who are despised by God, and also not the religion of Christians who reject the prophethood of Muhammad.”

have blessed with the guidance of Islam before their death, not the religion of the Jews who are despised by God, and also not the religion of Christians who reject the prophethood of Muhammad.”

17/19 This translation is based on a well-known exegetical hadith, which, however, many contemporary translators and exegetes choose not to base their interpretation on, partly because of its hostility towards pre-Islamic religions,

and partly because it narrows down a universal statement in the Qur’an to a

very particular meaning. Thalib, conversely, considers any omission of this hadith a falsification of the meaning of the Qur’an.

very particular meaning. Thalib, conversely, considers any omission of this hadith a falsification of the meaning of the Qur’an.

This points to a fundamental controversy over the role of exegetical

traditions in the interpretation and translation of the Qur’an and also to the inherent potential of politicizing that controversy.

#qurantranslationoftheweek 🌏

~JP~

traditions in the interpretation and translation of the Qur’an and also to the inherent potential of politicizing that controversy.

#qurantranslationoftheweek 🌏

~JP~

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh