1/6

Does India have a problem with 'just transition' of coal mining workers?

I spent some time today looking through the micro-data of the 2018-19 Periodic Labour Force Survey.

Thread.

Does India have a problem with 'just transition' of coal mining workers?

I spent some time today looking through the micro-data of the 2018-19 Periodic Labour Force Survey.

Thread.

2/6

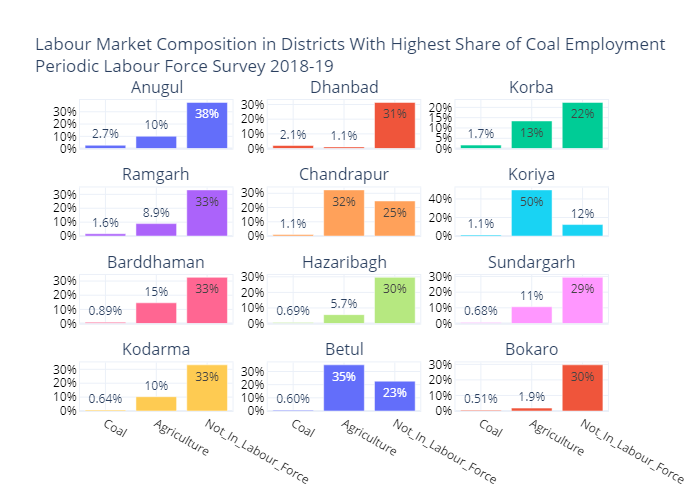

In the 12 districts with the highest reported shares of coal mining employment (primary usual status):

1. Agriculture employment was a larger reported employer than coal in all but one.

2. Labour market exclusion was 1-2 orders of magnitude larger than coal employment.

👇

In the 12 districts with the highest reported shares of coal mining employment (primary usual status):

1. Agriculture employment was a larger reported employer than coal in all but one.

2. Labour market exclusion was 1-2 orders of magnitude larger than coal employment.

👇

3/6

NB: exclusion from the labour market does not include people in education.

Thus, even in the most coal intensive districts, the challenge is not creating alternative employment for coal miners as we transition away from coal.

It's a problem 2 orders of magnitude larger.

NB: exclusion from the labour market does not include people in education.

Thus, even in the most coal intensive districts, the challenge is not creating alternative employment for coal miners as we transition away from coal.

It's a problem 2 orders of magnitude larger.

4/6

Jobs for:

1. The substantially larger part of the population still stuck in unproductive agriculture even in these districts.

2. For the population excluded from the labour market.

3. The 15-40% of the population in education, entering the labour market tomorrow 👇.

Jobs for:

1. The substantially larger part of the population still stuck in unproductive agriculture even in these districts.

2. For the population excluded from the labour market.

3. The 15-40% of the population in education, entering the labour market tomorrow 👇.

5/6

As long as coal districts continue with huge shares of their populations in what Lewis called the 'subsistance' sector, labour market outcomes for workers moving out of coal will continue to be terrible, regardless of what sectoral 'just transition' policies are implemented

As long as coal districts continue with huge shares of their populations in what Lewis called the 'subsistance' sector, labour market outcomes for workers moving out of coal will continue to be terrible, regardless of what sectoral 'just transition' policies are implemented

6/6

Thus, the framing of just transition policies needs to be much more expansive in a country like India. It is not about unaffordable payoffs or skilling programs of a few thousand miners (a la Spain).

It is about the country's and coal districts' entire development model.

Thus, the framing of just transition policies needs to be much more expansive in a country like India. It is not about unaffordable payoffs or skilling programs of a few thousand miners (a la Spain).

It is about the country's and coal districts' entire development model.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh