THREAD: More on the Neatness of God’s Handiwork

A 3 x 3 gematrial matrix,

a series of three weights,

and the rise of the constellation Libra (‘The Scales’!) on the day of Babylon’s fall.

What do these things have in common?

See below for my suggested answers.

A 3 x 3 gematrial matrix,

a series of three weights,

and the rise of the constellation Libra (‘The Scales’!) on the day of Babylon’s fall.

What do these things have in common?

See below for my suggested answers.

Over the last week, I’ve noticed what I *think* are some remarkable features of the text of Dan. 5.25–28.

Maybe you’ll agree.

Below are (what I take to be) the highlights.

For those who want the full details, I’ll attach a pdf.

Maybe you’ll agree.

Below are (what I take to be) the highlights.

For those who want the full details, I’ll attach a pdf.

SPOILER: In the end, Daniel beat Babylon’s star-gazers at their own game. And it revolves around a stolen menorah.

Daniel 5 is patterned around different threefold groups and structures. It consists of three paragraphs and thirty verses.

It contains three notable triplets, namely:

🔹 Daniel’s trio of attributes (‘light, insight, and wisdom’: 5.11, 14),

🔹 Daniel’s threefold ability (‘the ability to interpret dreams, explain riddles, and solve problems’: 5.12), and

🔹 Daniel’s trio of attributes (‘light, insight, and wisdom’: 5.11, 14),

🔹 Daniel’s threefold ability (‘the ability to interpret dreams, explain riddles, and solve problems’: 5.12), and

🔹 Belshazzar’s threefold reward (viz., ‘to be clothed in purple, adorned with a gold chain, and made the third most powerful man in the kingdom’),

which is mentioned three times (5.7, 16, 29).

which is mentioned three times (5.7, 16, 29).

Prepositions not included, the chapter’s (joint) third most common words—‘kingdom’ and ‘interpretation’—occur a total of nine times each (3 x 3).

And the chapter comes to its climax (in 5.24–30) with a nine-fold condemnation of Belshazzar’s idolatry,

And the chapter comes to its climax (in 5.24–30) with a nine-fold condemnation of Belshazzar’s idolatry,

…at which point Daniel’s announces the solution to Belshazzar’s riddle.

Daniel’s solution is predicated on a nine-syllable utterance (‘Meneh Meneh, Tekel, and Parsin’),

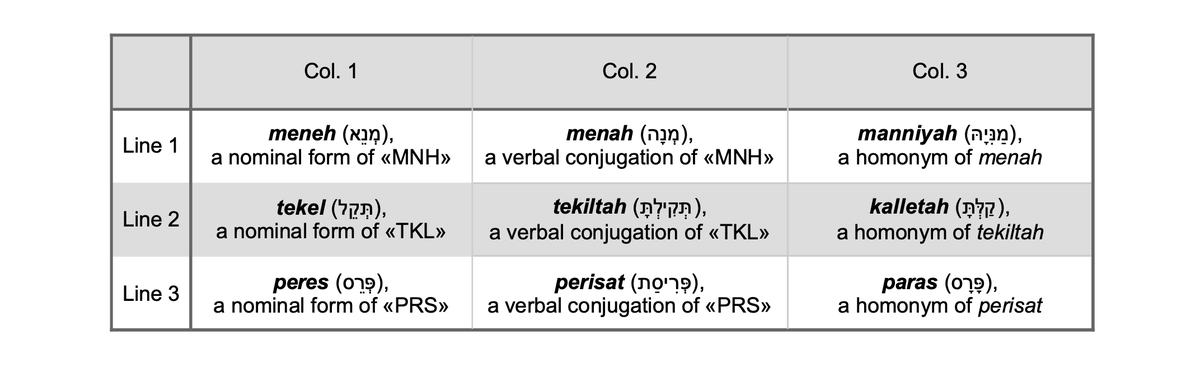

which he distils into a 3 x 3 matrix of characters:

Daniel’s solution is predicated on a nine-syllable utterance (‘Meneh Meneh, Tekel, and Parsin’),

which he distils into a 3 x 3 matrix of characters:

Finally, from the above matrix, Daniel generates a second 3 x 3 matrix...

...in which each of the triliteral roots of the words meneh, tekel, and peres are analysed (in typically Mesopotamian style) in three different ways:

...in which each of the triliteral roots of the words meneh, tekel, and peres are analysed (in typically Mesopotamian style) in three different ways:

The nature of the matrix’s construction is plain to see.

From meneh comes menah,

and from menah comes manniyah.

And from these words comes Daniel’s interpretation.

(The other lines work in much the same way.)

From meneh comes menah,

and from menah comes manniyah.

And from these words comes Daniel’s interpretation.

(The other lines work in much the same way.)

Twitter probably isn’t the place for the specifics of the Aramaic,

but we can summarise the situation roughly as follows.

but we can summarise the situation roughly as follows.

With apologies to any Semiticists present, we can think of the characters on Belshazzar’s wall as a string of consonants:

MNHMNHTKLWPRSYN

MNHMNHTKLWPRSYN

Daniel picks out three triliteral ‘roots’ from these consonants:

«MNH», «TKL», and «PRS».

First of all, he adds vowels and turns them into known Aramaic nouns:

meneh (5.26), tekel (5.27), and peres (5.28).

«MNH», «TKL», and «PRS».

First of all, he adds vowels and turns them into known Aramaic nouns:

meneh (5.26), tekel (5.27), and peres (5.28).

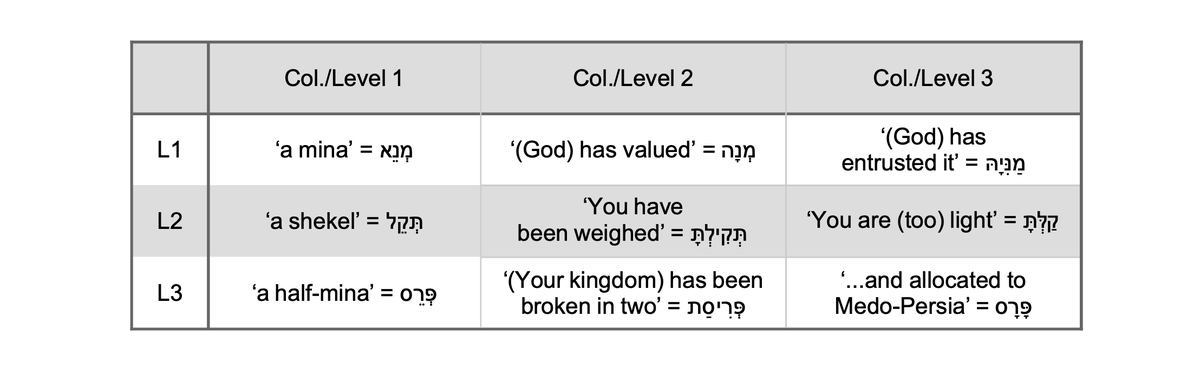

These nouns refer to weights.

The word meneh signifies a mina, i.e., 60 shekels.

The word tekel is the Aramaic pronunciation of the word ‘shekel’.

And the word peres can refer to either half a mina or half a shekel.

The word meneh signifies a mina, i.e., 60 shekels.

The word tekel is the Aramaic pronunciation of the word ‘shekel’.

And the word peres can refer to either half a mina or half a shekel.

Next, Daniel interprets each group of consonants not as a noun, but as a verb.

He revocalises meneh as menah (‘he reckoned/valued’),

tekel to tekiltah (‘you have been weighed’),

and so on.

He revocalises meneh as menah (‘he reckoned/valued’),

tekel to tekiltah (‘you have been weighed’),

and so on.

And finally Daniel provides a third interpretation of the same roots/consonants. (Details to follow.)

As such, we can schematise Daniel’s interpretation of Belshazzar’s riddle as a 3 x 3 grid,

where Column 1 describes a weight,

As such, we can schematise Daniel’s interpretation of Belshazzar’s riddle as a 3 x 3 grid,

where Column 1 describes a weight,

Column 2 is a sentence derived from the verb ‘behind’ that weight,

and Column 3 is prompted by a re-analysis of Column 2,

as shown below:

and Column 3 is prompted by a re-analysis of Column 2,

as shown below:

The flow/logic is as follows.

God has determined a kind of ‘mina of the land/kingdom of Babylon’;

that is to say, God has determined the worth of Babylon and, by implication, the kind of man who should rule it.

God has determined a kind of ‘mina of the land/kingdom of Babylon’;

that is to say, God has determined the worth of Babylon and, by implication, the kind of man who should rule it.

Belshazzar, however, doesn’t measure up (cp. 5.22–23).

He’s too ‘light’ by far.

Belshazzar’s kingdom will be divvied up and (re)distributed to a more apt empire—a twofold empire (Medo-Persia), an empire of sufficient weight to carry God’s plans forward.

He’s too ‘light’ by far.

Belshazzar’s kingdom will be divvied up and (re)distributed to a more apt empire—a twofold empire (Medo-Persia), an empire of sufficient weight to carry God’s plans forward.

Or, to put the point in terms of Nebuchadnezzar’s colossus, the golden head will give way to the arms of silver.

The consonants MNHMNHTKLWPRSYN don’t simply, therefore, represent particular weights, or even particular roots/verbs;

they also represent particular kings.

The consonants MNHMNHTKLWPRSYN don’t simply, therefore, represent particular weights, or even particular roots/verbs;

they also represent particular kings.

The mina represents Nebuchadnezzar;

the shekel represents Belshazzar;

and the two peres-weights represent Darius and Cyrus.

the shekel represents Belshazzar;

and the two peres-weights represent Darius and Cyrus.

That’s only, however, the tip of the iceberg.

The characters which make up Daniel’s 3 x 3 matrices have some remarkable properties. (Shouldn’t we expect that of characters written by God himself?)

The characters which make up Daniel’s 3 x 3 matrices have some remarkable properties. (Shouldn’t we expect that of characters written by God himself?)

Consider, for instance, how they highlight the presence and prominence of the number 91:

🔹 Daniel’s statement and interpretation of Belshazzar’s riddle consist of 91 letters.

🔹 Daniel’s statement and interpretation of Belshazzar’s riddle consist of 91 letters.

🔹 Both the uppermost row and the leftmost column of Daniel’s 3 x 3 grid of consonants have a gematrial value of 91.

🔹 The number 91 hints at the identity of the protagonist and antagonist in 5.26–28’s events,

since both the Aramaic term מלכא (‘the king’) as well as the Hebrew term האלהים (‘God’) have a value of 91. (Like his father, Belshazzar has chosen to mess with the wrong deity.)

since both the Aramaic term מלכא (‘the king’) as well as the Hebrew term האלהים (‘God’) have a value of 91. (Like his father, Belshazzar has chosen to mess with the wrong deity.)

🔹 And, finally, the weights mentioned by Daniel in his interpretation of Belshazzar’s riddle have a combined weight of 91 shekels,

since a shekel plus a peres (30 shekels) plus a mina (60 shekels) amounts to 91 shekels.

since a shekel plus a peres (30 shekels) plus a mina (60 shekels) amounts to 91 shekels.

Indeed, the three letters in the leftmost column of our grid (אלס) sum to 91 precisely because each of them represents one of Daniel’s weights:

alef (א) has a value of 1, lamed (ל) has a value of 30, and samech (ס) has a value of 60.

alef (א) has a value of 1, lamed (ל) has a value of 30, and samech (ס) has a value of 60.

These same letters also spell out the word סלא = ‘to be risen in the balances’ (Jastrow; cp. Lam. 4),

which has a very obvious application to Belshazzar.

Belshazzar has been outweighed by ‘the mina of the land’ (Nebuchadnezzar) on the other side of the balances.

which has a very obvious application to Belshazzar.

Belshazzar has been outweighed by ‘the mina of the land’ (Nebuchadnezzar) on the other side of the balances.

As such, the presence of the number 91 in our text is significant.

It connects Belshazzar’s riddle with its solution, and Belshazzar’s destiny with the riddle’s author.

It connects Belshazzar’s riddle with its solution, and Belshazzar’s destiny with the riddle’s author.

Other aspects of 5.25–28’s text are just as remarkable.

Below I’ll outline another.

Below I’ll outline another.

The guests at Belshazzar’s feast would have seen the inscription on the palace wall as a ‘sign’ in need of ‘interpretation’.

Yet, although the inscription was clearly a sign of some kind, it was not a normal sign.

It looked partly mathematical (or at least metrological),

Yet, although the inscription was clearly a sign of some kind, it was not a normal sign.

It looked partly mathematical (or at least metrological),

and it had been revealed to a king,

which was quite normal for a 6th cent. Babylonian sign.

Yet such signs typically identified the ruler whose future they concerned,

and included numbers to indicate how long those rulers would reign for (Wiseman 1985:90),

which was quite normal for a 6th cent. Babylonian sign.

Yet such signs typically identified the ruler whose future they concerned,

and included numbers to indicate how long those rulers would reign for (Wiseman 1985:90),

and Belshazzar’s riddle didn’t seem to do so—or at least not obviously.

Maybe, however, for those with eyes to see, it did.

And maybe God has encoded those details into the text as we have it today for the benefit of later generations.

Maybe, however, for those with eyes to see, it did.

And maybe God has encoded those details into the text as we have it today for the benefit of later generations.

Consider Nebuchadnezzar as he’s described in the text of Scripture.

Nebuchadnezzar first becomes a major figure in the Biblical narrative in 597 BC when he exiles Judah and instates a new king in Jehoiachin’s place,

Nebuchadnezzar first becomes a major figure in the Biblical narrative in 597 BC when he exiles Judah and instates a new king in Jehoiachin’s place,

which is when I take Nebuchadnezzar’s ‘golden reign’ to have begun.

(Ezekiel begins his ‘era of the exile’ at the same time, i.e., in the year 598t/597t BC: cp. Young 2004.)

(Ezekiel begins his ‘era of the exile’ at the same time, i.e., in the year 598t/597t BC: cp. Young 2004.)

Now, recall the scene described in ch. 5.

Daniel is brought before Belshazzar and is commanded to interpret the inscription/riddle on the king’s wall.

Daniel is brought before Belshazzar and is commanded to interpret the inscription/riddle on the king’s wall.

Daniel doesn’t immediately do so (5.17ff.).

Instead, he rewinds 60 years or so and begins to fill Belshazzar in on his ancestry.

He describes the glorious kingship God gave Nebuchadnezzar (5.18ff.).

Instead, he rewinds 60 years or so and begins to fill Belshazzar in on his ancestry.

He describes the glorious kingship God gave Nebuchadnezzar (5.18ff.).

He refers to Nebuchadnezzar as Belshazzar’s ‘father’—the head of Belshazzar’s dynasty (5.22ff.).

And then, finally, he provides his interpretation of Belshazzar’s riddle,

in which he depicts Nebuchadnezzar as a 60-shekel mina.

And then, finally, he provides his interpretation of Belshazzar’s riddle,

in which he depicts Nebuchadnezzar as a 60-shekel mina.

As such, the riddle/omen on Belshazzar’s wall seems to identify at least one king (on contextual grounds),

and it also seems to involve at least one number (60).

and it also seems to involve at least one number (60).

I personally believe it contains many other numbers besides,

the purpose of which is to identify the other parties involved in Belshazzar’s riddle.

Recall Daniel’s consonantal grid and its associated gematrial properties.

the purpose of which is to identify the other parties involved in Belshazzar’s riddle.

Recall Daniel’s consonantal grid and its associated gematrial properties.

As we’ve noted, in the backdrop of Belshazzar’s riddle stands the dynasty of Nebuchadnezzar and the prospect of its judgment,

and revealed in the leftmost column of Daniel’s grid is the identify of both the judge (האלהים) and the person about to be judged (מלכא).

and revealed in the leftmost column of Daniel’s grid is the identify of both the judge (האלהים) and the person about to be judged (מלכא).

Encoded in the other columns of Daniel’s grid is similar information.

🔹 The letters in the middle column (נקר) identify the nationality of the man who is about to enter the city, since they have the same value as פרסי = ‘a Persian’ (viz. 350).

🔹 The letters in the middle column (נקר) identify the nationality of the man who is about to enter the city, since they have the same value as פרסי = ‘a Persian’ (viz. 350).

They also happen to be an anagram of the word קרן = ‘a horn’, which associates the man in question with the Persian horn of ch. 8’s ram.

🔹 The reinterpretation of 5.25’s peres-weights (parsin) as half-shekels rather than half-minas—a well-known manoeuvre in Mesopotamian divination—identifies Cyrus’s Median counterpart,

since a meneh, a tekel, and (two) parsin amount to 62 shekels,

since a meneh, a tekel, and (two) parsin amount to 62 shekels,

which points towards the 62-year-old Darius (6.1). (Why would we be told Darius’s age if it wasn’t relevant in some way?)

🔹 And the letters in the rightmost column (מתף) identify both of Medo-Persia’s kings,

🔹 And the letters in the rightmost column (מתף) identify both of Medo-Persia’s kings,

since they have the same value as both the names ‘Darius’ (דָּרְיָוֶשׁ) and ‘Cyrus’ (כֹּרֶשׁ), viz. 520.

(It’s sometimes said you can prove anything with gematria. I disagree. For instance, no other names in Scripture have a value of 520.)

(It’s sometimes said you can prove anything with gematria. I disagree. For instance, no other names in Scripture have a value of 520.)

🔹 And over and above these details stands the God who has orchestrated them long ago,

whose identity is hinted at by means of the resonances between Daniel 5 and God’s declaration in Isaiah 45–47.

whose identity is hinted at by means of the resonances between Daniel 5 and God’s declaration in Isaiah 45–47.

In Isa. 45, God summons Cyrus by name and claims he will ‘loosen the loins/bladder’ of kings before him, which is what he does to Belshazzar.

In Isa. 46, God condemns Babylon’s idols of silver and gold, i.e., the idols present at Belshazzar’s feast.

In Isa. 46, God condemns Babylon’s idols of silver and gold, i.e., the idols present at Belshazzar’s feast.

And, in Isa. 47, YHWH challenges Babylon’s sorcerers and stargazers to rescue Babylon from disaster—that is to say, YHWH issues a challenge to the very diviners whom Belshazzar consults—,

though they do not rise to the occasion.

though they do not rise to the occasion.

Isa. 45–47 records all these statements of what YHWH will do from YHWH’s first person perspective (‘I am YHWH’, ‘I will take vengeance’, etc.),

with the exception of one verse.

In 47.4, YHWH’s speech is interrupted by a statement made by Israel,

with the exception of one verse.

In 47.4, YHWH’s speech is interrupted by a statement made by Israel,

namely, ‘Our Redeemer! YHWH of hosts is his name’ (גֹּאֲלֵנוּ יְהוָה צְבָאוֹת שְׁמוֹ),

which is the only statement of its kind in Isa. 45–47 and has the same gematrial value as Daniel’s 3 x 3 grid, viz. 961.

which is the only statement of its kind in Isa. 45–47 and has the same gematrial value as Daniel’s 3 x 3 grid, viz. 961.

A question, however, remains.

*When* will these things happen? That is to say, When will Babylon fall and Belshazzar be replaced by Darius and Cyrus?

The answer is hinted at in the first line of Daniel’s interpretation (מְנֵא מְנָה-אֱלָהָא מַלְכוּתָךְ).

*When* will these things happen? That is to say, When will Babylon fall and Belshazzar be replaced by Darius and Cyrus?

The answer is hinted at in the first line of Daniel’s interpretation (מְנֵא מְנָה-אֱלָהָא מַלְכוּתָךְ).

While the primary sense of the verb «MNH» in 5.26–28 is ‘to assess’, the verb can also have the sense ‘to limit a thing’s extent, to number its days/years’.

Per the hermeneutics of Mesopotamian interpretation, then, 5.26 can be read as follows:

Per the hermeneutics of Mesopotamian interpretation, then, 5.26 can be read as follows:

‘God has assigned your kingdom a limit of a mina’.

What might that mean?

My suggestion is as follows:

God has assigned Nebuchadnezzar’s kingdom a mina’s worth of years, i.e., a 60-year reign over Judah.

What might that mean?

My suggestion is as follows:

God has assigned Nebuchadnezzar’s kingdom a mina’s worth of years, i.e., a 60-year reign over Judah.

Put another way, God has assigned Nebuchadnezzar a year of dominion for every cubit of his golden image (3.1).

And, as Daniel appears before Belshazzar in 539 BC, the last of those 60 years has just begun,

which the lampstand is a tangible marker/memory of.

And, as Daniel appears before Belshazzar in 539 BC, the last of those 60 years has just begun,

which the lampstand is a tangible marker/memory of.

As such, the presence of the lampstand in ch. 5’s events is highly significant.

Picture the scene.

We have a king who is about to be judged.

We have a prophet (Daniel), who has just pronounced the verdict to which his name refers, viz. ‘the verdict of God’ (דניאל).

Picture the scene.

We have a king who is about to be judged.

We have a prophet (Daniel), who has just pronounced the verdict to which his name refers, viz. ‘the verdict of God’ (דניאל).

And, in the midst of it all, we have a lampstand taken from Jerusalem’s temple,

which resonates with its environment in a number of significant ways.

which resonates with its environment in a number of significant ways.

🔹 Insofar as it is a ‘vessel’ (מאן) of God (cp. 5.2–5), it looks forward to the first of the three roots inscribed on Belshazzar’s wall. (מאן is an anagram of מנא.)

🔹 As far its shape and nature are concerned, it is not dissimilar to a set of scales.

Indeed, the word employed to describe the lampstand’s six branches (קָנֶה) in Exodus 25 is employed by Isaiah to describe a set of (Babylonian!) scales in Isa. 46.

Indeed, the word employed to describe the lampstand’s six branches (קָנֶה) in Exodus 25 is employed by Isaiah to describe a set of (Babylonian!) scales in Isa. 46.

The lampstand’s branches can hence be seen as an illustration of the various comparisons made in Dan. 5.26–28, as shown below:

🔹 And the lampstand has various sixfold characteristics:

specifically, it has six branches; it has now spent 60 years in Babylon; and it has a weight of sixty minas (Exod. 25.39).

specifically, it has six branches; it has now spent 60 years in Babylon; and it has a weight of sixty minas (Exod. 25.39).

As such, it represents God’s perfect standard of judgment (60 x 60),

which serves to underscore Belshazzar’s lightness and inadequacy.

Ch. 5’s lampstand doesn’t only, therefore, shed light on God’s inscription in a physical sense (5.5);

which serves to underscore Belshazzar’s lightness and inadequacy.

Ch. 5’s lampstand doesn’t only, therefore, shed light on God’s inscription in a physical sense (5.5);

it also sheds light on it in a historical and theological sense.

Its presence in Belshazzar’s hall is a statement of why God’s judgment is about to fall on Belshazzar.

Its presence in Belshazzar’s hall is a statement of why God’s judgment is about to fall on Belshazzar.

THE NATURE OF AN INTERPRETATION

We hence come to ch. 5’s finale.

At first blush, the final scene of ch. 5 reads oddly.

Daniel pronounces Babylon’s downfall, and he is rewarded for his labours (!).

We hence come to ch. 5’s finale.

At first blush, the final scene of ch. 5 reads oddly.

Daniel pronounces Babylon’s downfall, and he is rewarded for his labours (!).

Yet, when we consider the nature of an ‘interpretation’ in Mesopotamian circles, things make more sense.

Daniel’s interpretation would have been seen to have removed the element of mystery in Belshazzar’s riddle and hence to have ‘depotentised’ it in some way.

Daniel’s interpretation would have been seen to have removed the element of mystery in Belshazzar’s riddle and hence to have ‘depotentised’ it in some way.

Meanwhile, the specific contents of Daniel’s interpretation would have been seen as avoidable—in technical terms, ‘atonable’—granted the performance of certain rituals.

Belshazzar would, therefore, have thought Daniel had done him a service.

Belshazzar would, therefore, have thought Daniel had done him a service.

Yet Belshazzar had overlooked an important fact.

The pronouncements of YHWH’s prophets were very different to the interpretations of Mesopotamia’s diviners,

since YHWH was a very different deity to his Mesopotamian counterparts.

What YHWH said came to pass.

The pronouncements of YHWH’s prophets were very different to the interpretations of Mesopotamia’s diviners,

since YHWH was a very different deity to his Mesopotamian counterparts.

What YHWH said came to pass.

It could not be reversed by means of ‘atonement rituals’ (cp. Isa. 47.11).

And it frequently came to pass in remarkably neat and ironic ways,

which it certainly did in the case of Daniel 5, as we’ll now see.

And it frequently came to pass in remarkably neat and ironic ways,

which it certainly did in the case of Daniel 5, as we’ll now see.

BEATEN AT THEIR OWN GAME:

Each year, the sun travels through the twelve constellations of the zodiac.

Consequently, the Mesopotamians associated each month of the year with a different constellation,

as many people still do today.

Each year, the sun travels through the twelve constellations of the zodiac.

Consequently, the Mesopotamians associated each month of the year with a different constellation,

as many people still do today.

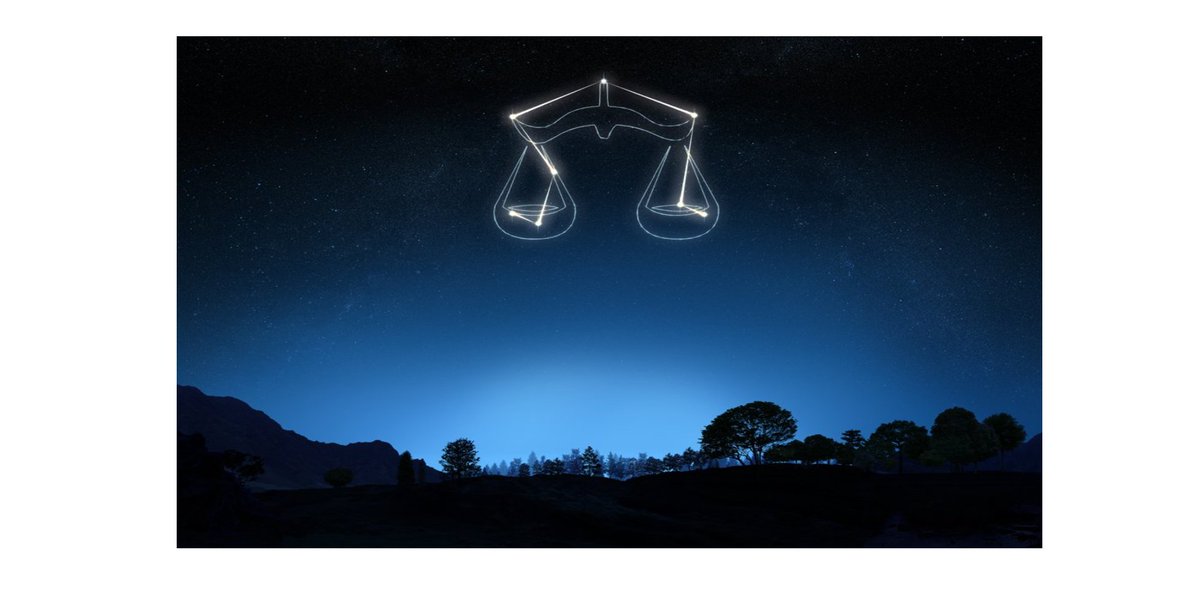

As Daniel uttered the words ‘mene mene, tekel, and parsin’, a significant constellation was due to rise in the skies over Babylon:

*Libra* was due to rise—a constellation referred to in Aramaic literature as mozenyah = ‘the scales’.

*Libra* was due to rise—a constellation referred to in Aramaic literature as mozenyah = ‘the scales’.

What better picture/summary of Belshazzar’s riddle could one want?

Indeed, the word mozenyah stands at the (epi)centre of Daniel’s interpretative grid (cp. 5.27).

Indeed, the word mozenyah stands at the (epi)centre of Daniel’s interpretative grid (cp. 5.27).

The fall of Babylon hence panned out as follows.

Just before sunrise on the 15th day of Tishri (the day began at nightfall in the Babylonian calendar), the time came for Libra to rise to prominence in the sky,

Just before sunrise on the 15th day of Tishri (the day began at nightfall in the Babylonian calendar), the time came for Libra to rise to prominence in the sky,

And Libra did in fact rise to prominence.

Some time later, Daniel told Belshazzar God had ‘weighed him in the balances’.

And, later that night, on the 16th day of Tishri, a Median commander named Ugbaru led a Persian-backed army into the city Babylon.

Some time later, Daniel told Belshazzar God had ‘weighed him in the balances’.

And, later that night, on the 16th day of Tishri, a Median commander named Ugbaru led a Persian-backed army into the city Babylon.

Shortly afterwards, Belshazzar was slain (5.30).

Daniel’s final words to Belshazzar (מדי ופרס) were hence fulfilled to the very letter,

as was Belshazzar’s final word to Daniel (תִּשְׁלַט = ‘You will reign!’: 5.16),

and Daniel beat Babylon’s star-gazers at their own game.

Daniel’s final words to Belshazzar (מדי ופרס) were hence fulfilled to the very letter,

as was Belshazzar’s final word to Daniel (תִּשְׁלַט = ‘You will reign!’: 5.16),

and Daniel beat Babylon’s star-gazers at their own game.

‘Let those who gaze at the stars...make known what is to come upon you!’ was YHWH’s challenge (Isa. 47.13),

and it went entirely unanswered.

Contra to popular opinion, the stars were not autonomous sources of power and wisdom,

able to be directed to Babylon’s own ends.

and it went entirely unanswered.

Contra to popular opinion, the stars were not autonomous sources of power and wisdom,

able to be directed to Babylon’s own ends.

They were instruments in the hand of the Most High God, which he directed to spell out Babylon’s fate.

Babylon’s star-gazers expected a sign in the earth to tell them what would come to pass on the earth—in their terms, šiṭir šamē = ‘an inscription in the heavens’—,

Babylon’s star-gazers expected a sign in the earth to tell them what would come to pass on the earth—in their terms, šiṭir šamē = ‘an inscription in the heavens’—,

and YHWH provided them with precisely such a sign/inscription.

He even gave them one on the earth.

And yet Babylon’s seers were blind to the work of God.

Her wise men were shown to be fools, and her ruler to be powerless.

He even gave them one on the earth.

And yet Babylon’s seers were blind to the work of God.

Her wise men were shown to be fools, and her ruler to be powerless.

FINALLY...

A final question remains.

Is what we’ve considered above simply an account of a godless king’s judgment? Or is it also Gospel?

The answer, I submit, is the latter.

A final question remains.

Is what we’ve considered above simply an account of a godless king’s judgment? Or is it also Gospel?

The answer, I submit, is the latter.

The Gospels portray Jesus as a Messiah who bore the punishment which God’s enemies deserved to bear.

He was enshrouded in the darkness of Isaiah 13–14 (cp. Matt. 24.29, 27.45).

He was given Jeremiah’s cup of wrath to drink (cp. Mark 10.37–40).

He was enshrouded in the darkness of Isaiah 13–14 (cp. Matt. 24.29, 27.45).

He was given Jeremiah’s cup of wrath to drink (cp. Mark 10.37–40).

And, finally, he was pierced by Zechariah’s sword of divine justice (Zech. 12.10, 13.7, Matt. 26.31).

Jesus can also, I submit, be seen as the one who bore the curse of Daniel 5.

He was not, of course, a ‘light’ man (like Belshazzar).

Jesus can also, I submit, be seen as the one who bore the curse of Daniel 5.

He was not, of course, a ‘light’ man (like Belshazzar).

Yet Jesus did undergo a process which can be summarised by means of the verbs «MNH», «TKL», and «PRS».

As a man, Jesus was worth a mina (and more);

he was ‘the mina of the king’ in the truest sense of the term.

And yet Jesus was ‘set at naught’ by his people,

As a man, Jesus was worth a mina (and more);

he was ‘the mina of the king’ in the truest sense of the term.

And yet Jesus was ‘set at naught’ by his people,

treated like a lowly shekel of a man,

and betrayed for a mere peres (30 shekels of silver).

Thereafter, Jesus was ‘counted’ (MNH) as a transgressor (per Isa. 53.12) and ‘hung’ (TKL) on a cross.

and betrayed for a mere peres (30 shekels of silver).

Thereafter, Jesus was ‘counted’ (MNH) as a transgressor (per Isa. 53.12) and ‘hung’ (TKL) on a cross.

And, as he ‘spread/stretched out’ (PRS) his hands, he was left to die in darkness, an inscription of God’s verdict on him etched above his head (cp. John 19.19ff.).

Hence, in AD 30, the scales of justice became the cross of justice,

Hence, in AD 30, the scales of justice became the cross of justice,

and the meneh meneh (מנא מנא) of Belshazzar’s riddle found its answer in Jesus, the manna (מנא) from heaven,

the one who did not consult the stars but determined (מנה) their number (Psa. 147.4),

the one who did not consult the stars but determined (מנה) their number (Psa. 147.4),

the one who did not preface his statements with words of judgment (מנא מנא), but with words of grace and truth (אמן אמן = ‘Amen, Amen!’),

the one who has been reckoned (מנא) among the transgressors so we might be reckoned (מנא) righteous.

THE END.

academia.edu/44021917/

the one who has been reckoned (מנא) among the transgressors so we might be reckoned (מנא) righteous.

THE END.

academia.edu/44021917/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh