Both the Advocate General for Scotland and the Attorney General have argued in recent days, that section 19 of the Human Rights Act 1998 provides a precedent for the UK legislating contrary to its international obligations.

[THREAD] [1/15]

[THREAD] [1/15]

The Government's argument seems to be that this illustrates both how:

(a) domestic law and international law sometimes come into conflict; and

(b) this sometimes justifies Ministers acting contrary to international law and/or Parliament legislating contrary to it. [2/15]

(a) domestic law and international law sometimes come into conflict; and

(b) this sometimes justifies Ministers acting contrary to international law and/or Parliament legislating contrary to it. [2/15]

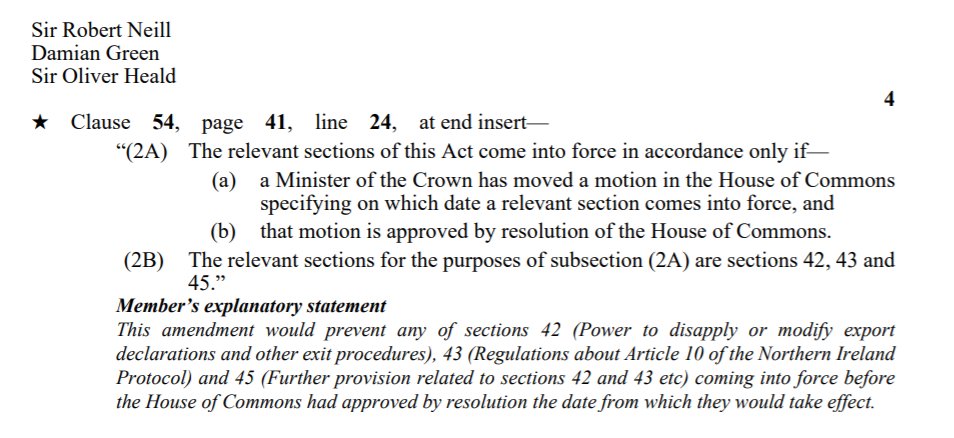

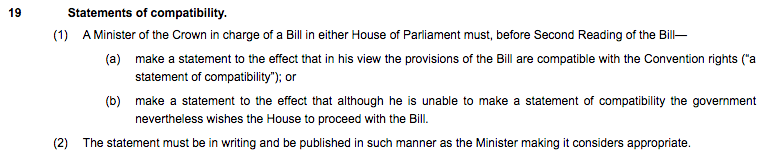

Specifically, they point to section 19 of the Human Rights Act 1998. This provision imposed a new obligation on Ministers when introducing a Bill before Parliament.

A Minister has to make one of two statements, in writing, when they are introducing a Bill. [3/15]

A Minister has to make one of two statements, in writing, when they are introducing a Bill. [3/15]

The first type of statement is what happens almost all the time: one "to the effect that in his view the provisions of the Bill are compatible with the Convention rights".

This statement is made after an internal vetting exercise by the relevant Government department [4/15]

This statement is made after an internal vetting exercise by the relevant Government department [4/15]

The expectation is the Government will, if possible, seek to legislate compatibly with the ECHR, and to make sure legislation is compatible *before* introducing a Bill.

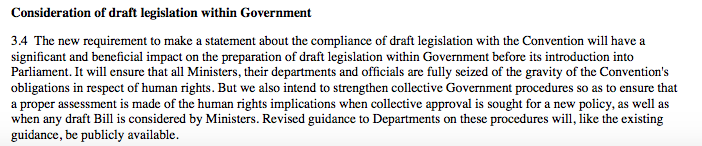

Here's what the Government's white paper in October 1997 said of the measure: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/upl… [5/15]

Here's what the Government's white paper in October 1997 said of the measure: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/upl… [5/15]

The purpose of section 19 was to "ensure that all Ministers, their departments and officials are fully seized of the gravity of the Convention's obligations in respect of human rights."

Far from justifying breaking international law, it was intended to improve compliance. [6/15]

Far from justifying breaking international law, it was intended to improve compliance. [6/15]

The same 1997 white paper acknowledged that sometimes a "statement of compatibility" couldn't/shouldn't be made.

This happens where there is a "risk" of non-compliance with the ECHR or "the arguments raised [about whether proposed legislation complies] are not clear cut". [7/15]

This happens where there is a "risk" of non-compliance with the ECHR or "the arguments raised [about whether proposed legislation complies] are not clear cut". [7/15]

The then Lord Chancellor (Derry Irvine) was clear at Lords 2nd reading:

"Ministers will obviously want to make a positive statement whenever possible. That requirement should therefore have a significant impact on the scrutiny of draft legislation within government." [8/15]

"Ministers will obviously want to make a positive statement whenever possible. That requirement should therefore have a significant impact on the scrutiny of draft legislation within government." [8/15]

He was also of the view that:

"If a Minister's prior assessment of compatibility (under Clause 19) is subsequently found by declaration of incompatibility by the courts to have been mistaken, it is hard to see how a Minister could withhold remedial action." [9/15]

"If a Minister's prior assessment of compatibility (under Clause 19) is subsequently found by declaration of incompatibility by the courts to have been mistaken, it is hard to see how a Minister could withhold remedial action." [9/15]

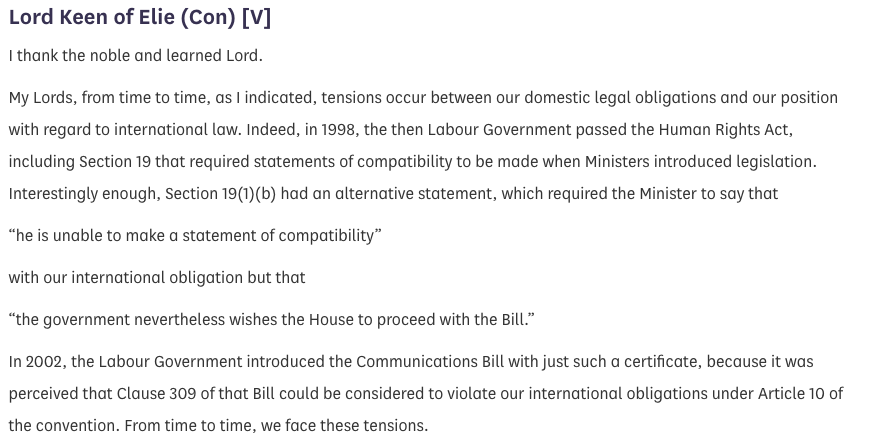

So let's go to specific examples. Lord Keen drew to the House of Lords' attention the Communications Bill in 2002. The Labour Government said it couldn't issue a statement of compatibility.

But what was this actually about? [10/15]

But what was this actually about? [10/15]

The Gov't was concerned that, in retaining an *existing* ban on political advertising in broadcast media, the UK *might* be vulnerable to litigation. There had been an adverse ECtHR ruling about a similar ban in Switzerland. The relevant Minister (Tessa Jowell) said this [11/15]

Key differences between that situation and the current one:

(a) the Government wasn't admitting its proposed legislation violated international law

(b) it maintained there were "very strong arguments" that they were HRA/ECHR compliant

(c) they were later proved right.

[12/15]

(a) the Government wasn't admitting its proposed legislation violated international law

(b) it maintained there were "very strong arguments" that they were HRA/ECHR compliant

(c) they were later proved right.

[12/15]

In Animal Defenders International v UK (2013, hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-1192…) the European Court of Human Rights affirmed that the ban on political advertising in broadcast media was not a violation of Article 10 after all.

In short: the Act didn't violate international law. [13/15]

In short: the Act didn't violate international law. [13/15]

There was never a suggestion that, if the ECtHR found the other way, the UK Gov't would have simply ignored the ruling. Whenever an adverse ruling has come, the UK Gov't of the day has *always* considered and attempted remedial action (including on prisoner voting). [14/15]

The purpose of the "cannot make a statement of compatibility" statement in 2002 was to draw Parliament's attention to a litigation risk associated with what was in any case an existing UK law being restated.

This is clearly not the same as the current situation. [15/15]

This is clearly not the same as the current situation. [15/15]

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh