1/ #GLS is not an objective measure, it's totally method dependent, and therefore with no gold standard, and no possibility of validating measurements. Why is this?

2/ Let's go into the definition of strain. The Lagrangian definition is S = (L-L0)/L0, change in length divided by original length. For GLS, that means (roughly) longitudinal shortening / end diastolic length.

3/ Since longitudinal shortening can be measured by longitudinal M-mode as MAPSE, this means GLS can be measured as MAPSE / end diastolic length.

4/ In the HUNT study, Mean MAPSE was 1.58 cm, with less than 1 mm Difference between mean of 2, 4 or six walls. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29399886/ Mean end diastolic mid LV length was 9.24 cm (unpublished), giving a mean GLS of -17.1%

5/But this measure is only related to this specific choice of reference length (denominator). We previously chose the straight line from apex to the mitral points, calculating strain per wall and mean. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29399886/

6/ This was more robust, the straight lines were closer to wall length, giving a measure closer to wall strain. But it's evident that this mean WL is a little longer than LVL,

9,47cm, and mean GLS by this denominator was -16.3%, lower absolute, because of the higher denominator

9,47cm, and mean GLS by this denominator was -16.3%, lower absolute, because of the higher denominator

7/ Following the curved wall, would give even longer WL, and lower GLS, evident from the fig. We didn't do this exercise, as manual drawing would be to variable, and HUNT3 is vivid7 data. It could be done now, by automated methods in HUNT4, with better data, (If interesting).

8/ So even with these straightforward methods, the choices of denominator influences strain values, and there is no ground truth. Speckle tracking opens a new can of worms, as the algorithms are "black boxes", proprietary to vendors, and subject to change w/software versions

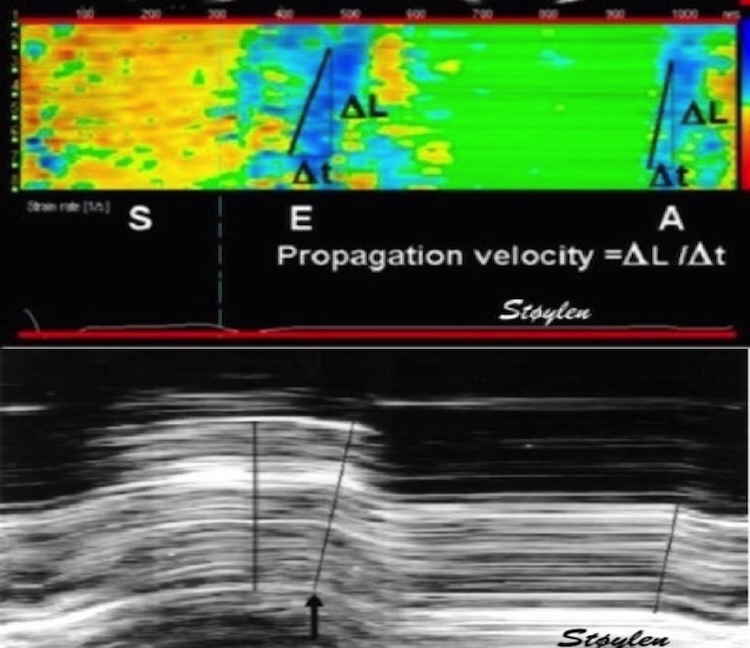

9/ There are, however some general priciples. In general, ST GLS tends to give higher absolute values, around -19 - -20%. Thus, even having curved ROIs following the walls ST draws in the opposite direction from the method outlined in tweet 7/. Why is this?

10/ Speckle tracking in general not only have curved ROIs, but also tracks crosswise motion of the speckles. As the wall thickens, this means that speckles move inwards in the cavity, in this example it's the endocardial boundary

11/ This is most pronounced at the endocardial border, leads so, but still present in the midway, and least at the external LV border. Most applications use either endocardial border, or a thick ROI, where mean motion most closely corresponds to the midwall

12/ But what happens when tracking a curved boundary that moves inward toward the curvature centre? Exactly, it becomes shorter. This effect is there, even when there is no longitudinal shortening, best illustrated with circumferential shortening.

13/ Circumferential strain is negative (shortening), but as seen by the unmoving diameter, this is *only* due to inward motion, which is a function of external circumferential shortening *and* wall thickening. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31673384/

14/ But this means that tracking derived GLS actually over estimates the longitudinal shortening, by incorporating some curvature shortening, which again is mainly wall thickening. In my opinion, this is another systematic error in ST derived GLS.

15/ And as this inward motion due to wall thickening is most pronounced at the endocardium (due to full wall thickening, as opposed to midwall, which only relates to outer half thickening), this is probably some of the basis for the unsound notion of "layer strain".

16/ In addition, the black box ST applications all have complex algorithms with different choices for

-Assumptions of LV shape and ROI width

-Number, size and stability of speckles

-Spline smoothing along the ROI and weighting of the AV -plane motion

-Etc.

-Assumptions of LV shape and ROI width

-Number, size and stability of speckles

-Spline smoothing along the ROI and weighting of the AV -plane motion

-Etc.

17/ Interestingly, we developed an in-house application for strain, tracking kernels longitudinally by TDI and transversely by ST, calculating segmental and global strain. It gave nearly the same GLS as the linear method in 5/.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19946115/

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29399886/

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19946115/

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29399886/

18/ I would expect it to be subject to the same error by inward tracking as ST, but as this used TDI data with a low underlying B-mode FR and lateral resolution, the lateral tracking may have been so poor, the technical shortcoming offset the systematic error.🤯

unroll @threaderapp

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh