A thread (1/21)

Let's talk about the "deficit" that isn't. The conventional way to talk about the government's fiscal position is to look at the difference between how much money the Government spends (G) and how much it collects via Taxation (T).

Let's talk about the "deficit" that isn't. The conventional way to talk about the government's fiscal position is to look at the difference between how much money the Government spends (G) and how much it collects via Taxation (T).

G > T means the government is spending more than it collects in tax payments. Convention has us refer to this as a fiscal "deficit."

G < T means the government is spending less than it collects in tax payments. Convention has us call this a fiscal "surplus."

G < T means the government is spending less than it collects in tax payments. Convention has us call this a fiscal "surplus."

So a "deficit" (G > T) implies a "lack of" something, a shortfall, or a "deficiency."

e.g. If the government spends $100 but only collects $90 in tax payments, we're told that the government is "short" $10.

e.g. If the government spends $100 but only collects $90 in tax payments, we're told that the government is "short" $10.

We're taught that the government "borrows" 10 dollars in to cover the "shortfall."

"Borrowing" happens when the government sells bonds (Treasuries in the US, gilts in the UK, JGBs in Japan, etc.)

"Borrowing" happens when the government sells bonds (Treasuries in the US, gilts in the UK, JGBs in Japan, etc.)

When G > T and bonds are sold, we are told than the government's "borrowing" drives up the "national debt."

Then, of course, we're told that the "debt" has to be "paid back," and panic sets in.

I have a huge problem with all of this. Let me explain.

Then, of course, we're told that the "debt" has to be "paid back," and panic sets in.

I have a huge problem with all of this. Let me explain.

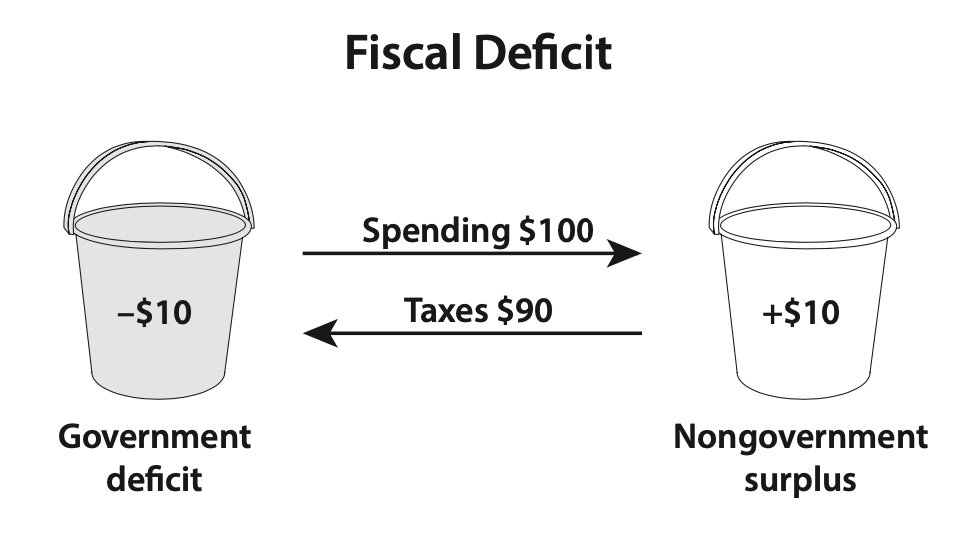

Here's an image from my book, The Deficit Myth. It illustrates a core tenet of MMT, namely that when G>T, the government is ADDING dollars (or pounds or yen, etc.) to the non-government part of the economy. publicaffairsbooks.com/titles/stephan…

The image adopts the conventional framing of G>T as a government "deficit." I think we should change that framing. Here's why: as @wbmosler likes to say, "the government neither has nor doesn't have money."

What that means, in my Two Bucket model, is that the government's bucket is special. Why? Because it is the currency-issuer. And that means it has an infinity bucket. ∞

(Take a deep breath, I know about inflation)

(Take a deep breath, I know about inflation)

The government doesn't reach into its bucket and grab some pre-existing 💵 (or 💷, or 💴). The government spends its currency into existence when it buys goods & services from the non-government sector. Spending gives rise to new💵, which is added to the non-government bucket.

The government pulls something out of nothing. That is the power of the infinity bucket. (Otherwise known as the Congressional power of the purse.) Think of the $2.2 trillion CARES Act, which conjured $2.2 trillion into existence from the infinity bucket.

When the government adds more dollars than it subtracts, it makes sense to say that the government is augmenting any *surplus* in non-government bucket. But does it make sense to describe the government bucket as being in *deficit* ?

Lots of people are getting anxious right now because the US government is expected to run a fiscal "deficit" of roughly $4 trillion (mostly due to the ~$3 trillion in added spending due to COVID-19).

But what, exactly, is the government "short"? The answer, is nothing. Think about it, what is $3 or $4 trillion subtracted from infinity? Answer: ∞

By the way, the same is true for G < T. Governments that are eager to restore fiscal "surpluses" are missing the point entirely. (Looking at you 🇦🇺)

What is the impact of, say, a $30 billion fiscal "surplus" when you add it to the infinity bucket? 🙃 It's still infinity!

What is the impact of, say, a $30 billion fiscal "surplus" when you add it to the infinity bucket? 🙃 It's still infinity!

As MMT shows, currency-issuing governments face no purely financial constraints (there is an inflation constraint). The government can't spend an infinite number of because there aren't an infinite number of goods and services available for sale in .

It can, however, purchase whatever is *available for sale* in its own currency, including all unemployed labor.

Bottom line: you can debit (or credit) the infinity bucket until the cows come home, but it will not alter the spending capacity of a monetary sovereign.

Bottom line: you can debit (or credit) the infinity bucket until the cows come home, but it will not alter the spending capacity of a monetary sovereign.

(Yes, I know about "confidence." Yes, there are historical examples of governments abusing these powers. A collapse of confidence (often after loss of war), means the supply of goods & services available for sale in the government's own currency collapses. MMT understands this.)

The bigger points:

G > T doesn't draw down the supply of available funds, and G < T doesn't top them up. It's a bottomless bucket that doesn't "hold" anything. Accounting conventions have us using words like "deficits" and "surpluses," but that really muddies the waters.

G > T doesn't draw down the supply of available funds, and G < T doesn't top them up. It's a bottomless bucket that doesn't "hold" anything. Accounting conventions have us using words like "deficits" and "surpluses," but that really muddies the waters.

There is no deficit--i.e. no shortfall that has to be atoned for ("paid back") in the future. Spending from the infinity bucket creates the currency that pays for the spending. Everything is "paid for" at the point of purchase.

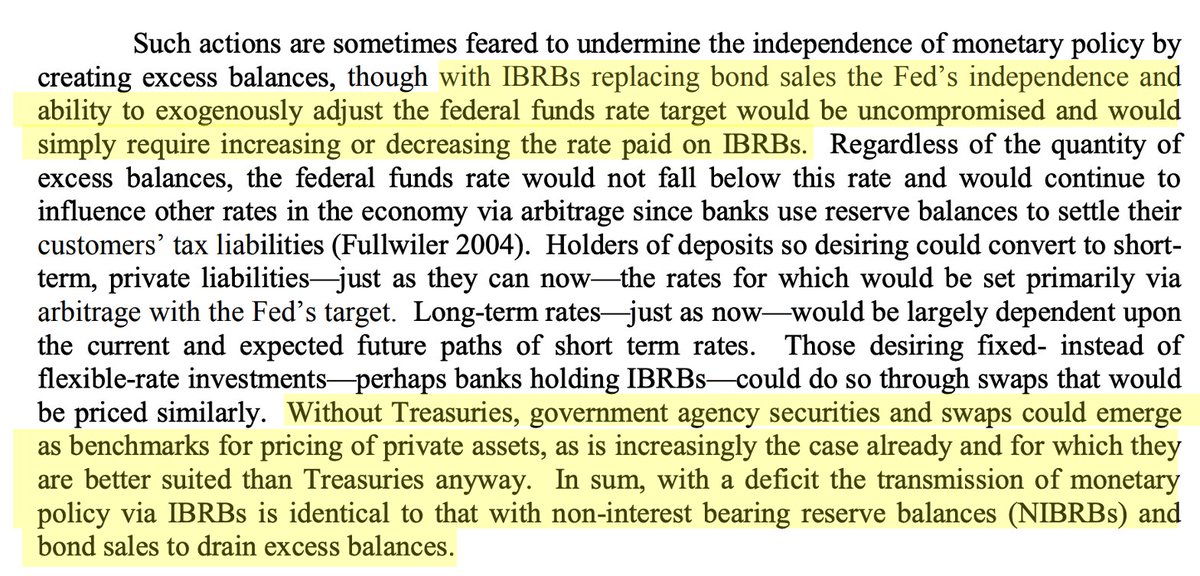

But what about "the debt"? More unfortunate terminology. Chapter 4 of my book is titled "The National Debt (That Isn't) The bonds are just the dollars that were spent into existence but not taxed away. They exist as part of the savings & wealth of the non-government sector.

We don't have a deficit problem (there is no deficit). We don't have a debt problem. We have a communication problem. /end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh