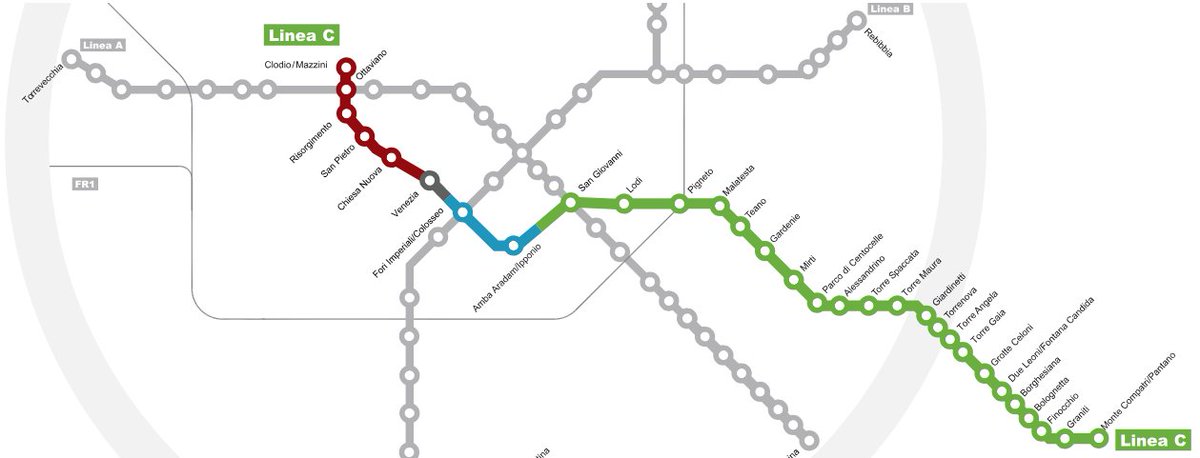

1/ The visitors of Rome remark that, for a 3.5m metro region, the subway network of the Eternal City is severely underdeveloped:

2 (and a half) lines

60 km

73 stations

A thread to try to explain why Rome has the worst rail transit among European capital cities

2 (and a half) lines

60 km

73 stations

A thread to try to explain why Rome has the worst rail transit among European capital cities

2/ This is a reparatory thread for Rome, ousted in round 1 in #RapidTransitBracket by @AlonLevy by London. Even if the defeat was deserved, putting the oldest metro network in the same bracket with the last European major capital city to get one, was an unfair pairing.

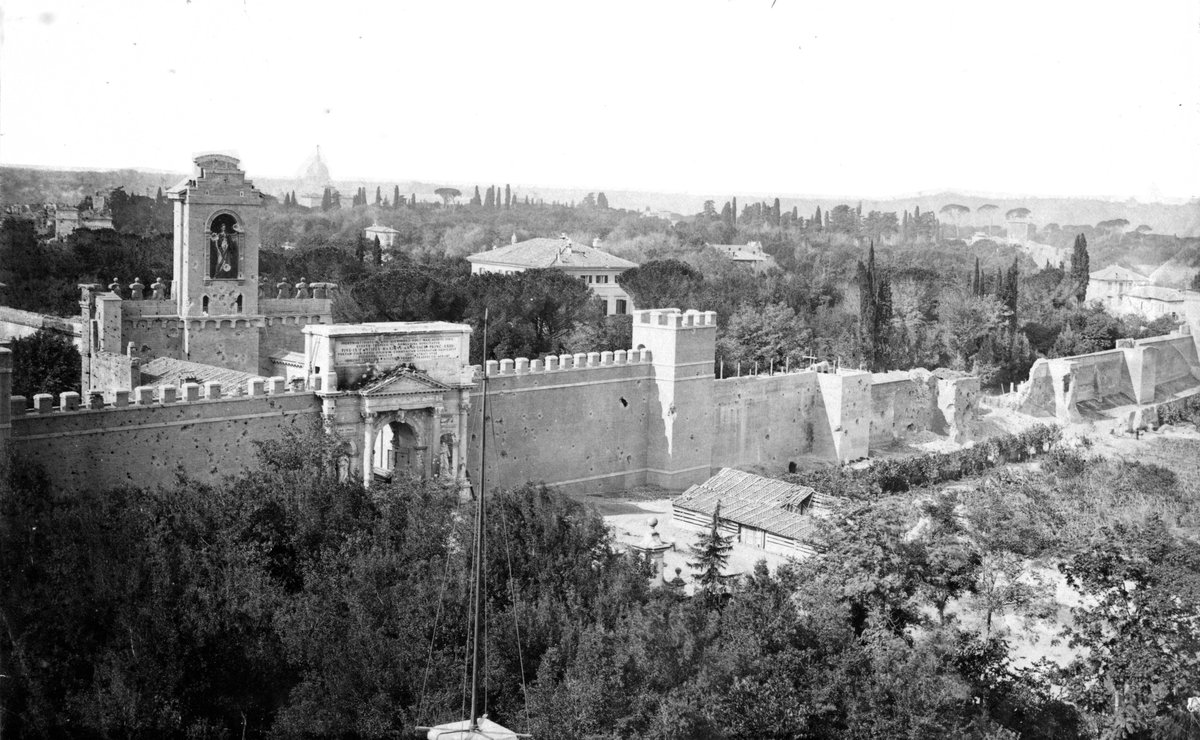

3/ Rome, despite its age, it’s a young capital city. When the Pope was finally kicked off in 1870 and the city became the capital of Italy, it was barely a large village of 212k inhabitants.

London had 3.8m, Paris 1.8m, Berlin 826k, Madrid 333k.

London had 3.8m, Paris 1.8m, Berlin 826k, Madrid 333k.

4/ Even if population growth accelerated in the following decades, it had barely reached half a million on the eve of WWI. It’s only in the 1920-30s that the population started booming, reaching 1,15m in 1936. And this is when planning for a metro network started.

5/ Some modern commuter railways were already developing by then, like the Rome-Ostia-Lido, opened in 1928, the Roma Nord, opened in 1932 with an u/g city terminus. Others were under construction, like the Porta Maggiore-Torre Spaccata, never finished b/c of the onset of WW2

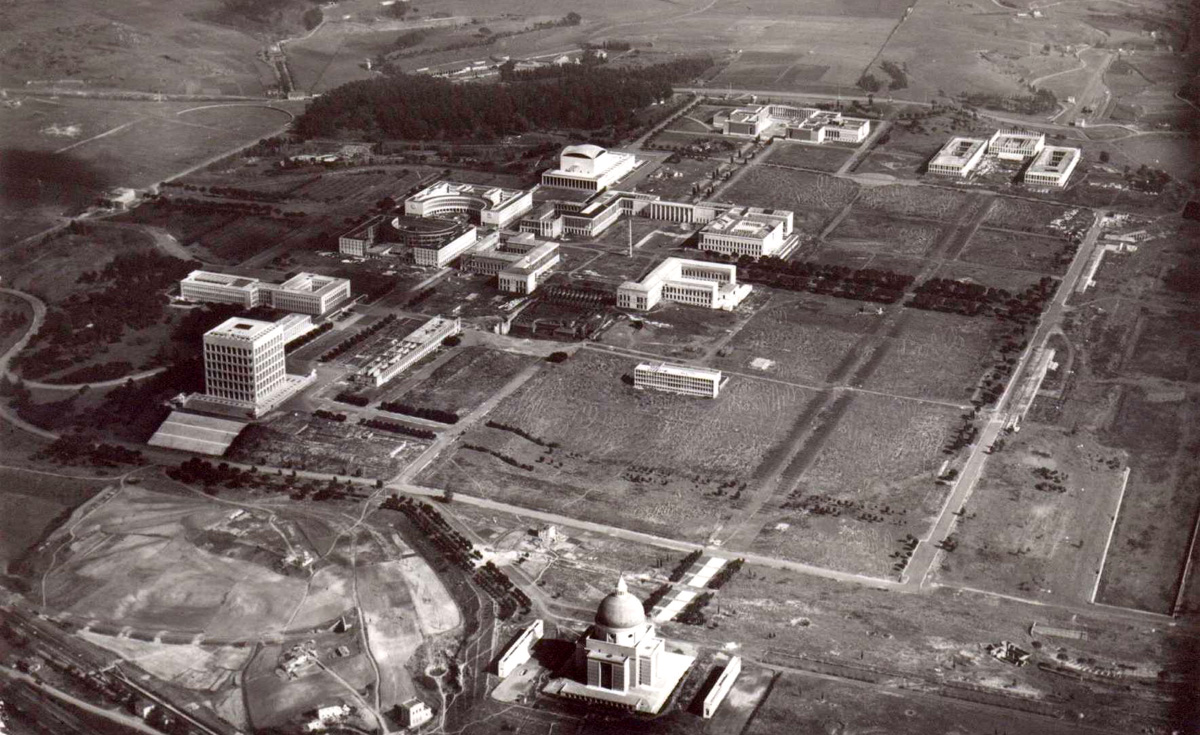

6/ But the first real metro was the railway connecting Roma Termini to the E.U.R. 42 Exposition site, intended to celebrate the 20 years of the Fascist regime. Events turned differently and works of both the metro and the Expo were suspended during WWII

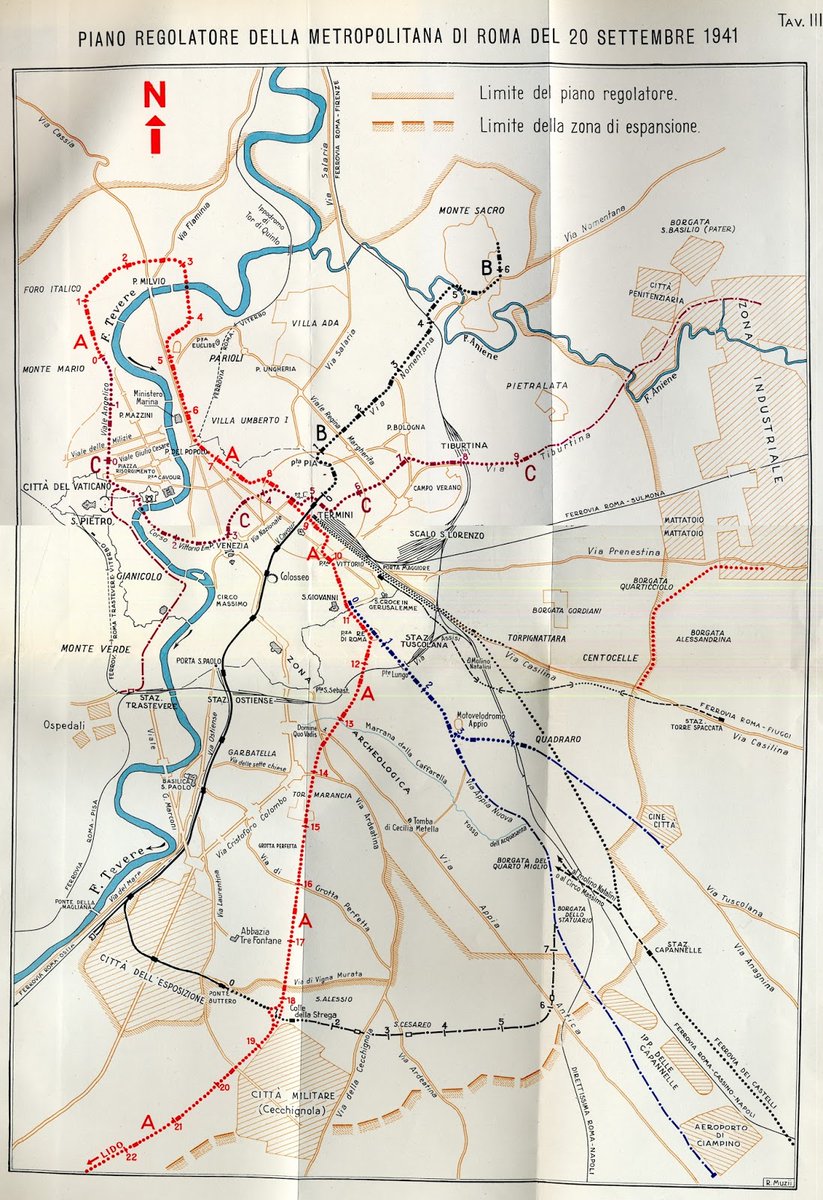

7/Despite the war, the first real masterplan envisioning the construction of a 3-line network was made in 1941. It shows the then u/c Termini-E.U.R. line (black), to be integrated into the future line B.

8/ Running underground within the city center and a/g along the Roma-Lido outside, doubling that commuter line with closer stops, it was built just under the surface near the majestic remains of ancient Rome and its terminus, at Roma Termini, boast a classic vaulted ceiling

9/ As works were resumed not long after the war, the line was finally opened in 1955, as the first proper metro line in Italy. But it remained the only one in Rome for decades, despite the dire need for more rail transit in the booming postwar city, that preferred to promote cars

10/ Even though the construction of the second line (line A) was approved in 1959, works started only in 1964. Planned to be built mainly in C&C, works were halted several times because of archeological findings and restarted with a tunnel boring machine in the early 70s

11/ The whole line A between Cinecittà and Ottaviano-San Pietro was finally opened in 1980. In the following years, despite grandiose plans, the network kept growing at an incredibly low pace, with the first extension of line B north of Termini opening only in 1990

12/ During the 1990s, grandiose plans are drawn again for new lines and extensions to be opened by the 2000 Jubilee, but only minor extensions for line A and the northern part of line B are finally opened (with a dull postmo rapidly ageing architecture).

13/ It is only in the late 1990s that a new plan based on a 4-line network is approved and Roma Metropolitane, an agency modeled after Metropolitana Milanese, is created and charged to supervise the design and construction of lines C, D + other extensions and LRT projects.

14/ Works on line C, an heavy rail with automated AnsaldoBreda trains, start in 2007. The line is planned to reach far out of the GRA, the ring motorway, reusing part of the infras built in the 1990s for the Roma-Pantano LRT. The outer section opened in stages from 2014

15/ But the problems begin with the central section.The San Giovanni-P.zza Venezia stretch through the Coliseum (blue) is experiencing delays and costs escalation. But the further stretch through the earth of the Baroque and Renaissance core of Rome (red) is even more challenging

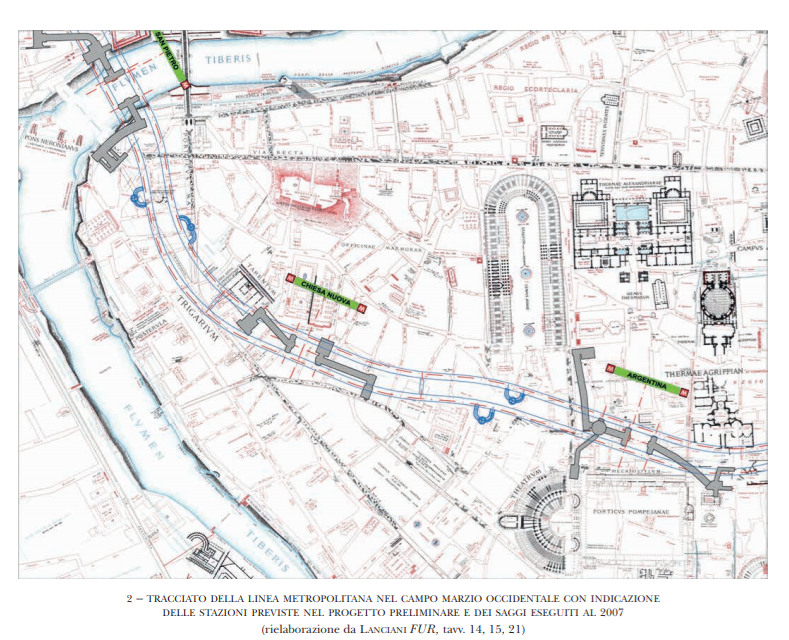

16/ At first, the line was intended to use larger TBMs to accommodate both tracks and platforms, as there is no space for C&C and to avoid two dozen meters of archeological layers. Preliminary archeological investigation proved that even that option was extremely difficult.

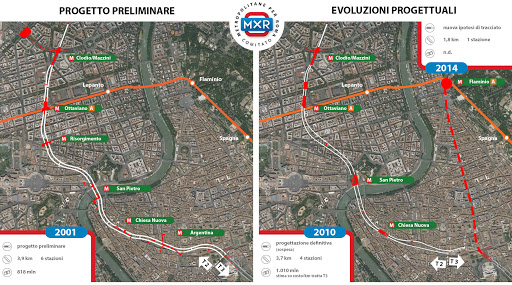

17/ The project of the central section underwent several modifications, with station after station shelved for archeological risk, to the point that the constructor proposed in 2011 a non-stop tube under the densest part of the city. A complete non-sense, transport-wise.

18/ Mismanagement, skepticism about the actual feasibility, endless political changes at the municipal level have put the project on a nightmarish path of continuous changes, Stop&Go and endless project revisions, with the results one can expect: raising costs and delays.

19/TBMs are now stopped under P.zza Venezia, waiting for the umpteenth project revision and waiting for funding for the costly and delicate city center stretch. The destiny of the project is unclear, even if it's probably going to be finished sometimes at the end of the decade🤞

20/To finance line D, the cash-strapped municipality engaged in a complicate PPP scheme, with development rights (sometimes far from stations) traded in lieu of monetary contributions to the builder. A complete failure. The project is now halted, waiting for a complete reboot

21/This is how Rome ended up with such a tiny and insufficient metro network. A mix of real difficulties in dealing with the complicate environment over and under the ground,coupled with lack of political commitment, and a less than optimal management of construction and planning

22/ The result is a noisy and congested city with the highest per capita car ownership rate among European peers and even compared to other Italian cities, like Milan and Naples. And that is really a pity.

https://twitter.com/ChittiMarco/status/1269400050754519040?s=20

23/ A final positive note: the works for line C are turning out to be a bonanza for archeologists, that are discovering infinite treasures that will be on display at the new stations once finished. Hoping I will be alive the day they open to see them.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh