1/n

Yesterday Xi Jinping announced that China would peak its emissions and work towards net zero emissions by 2060.

What does this mean for India?

A short thread on why India is fundamentally different from China, and how it could respond in its climate diplomacy.

Yesterday Xi Jinping announced that China would peak its emissions and work towards net zero emissions by 2060.

What does this mean for India?

A short thread on why India is fundamentally different from China, and how it could respond in its climate diplomacy.

2/n

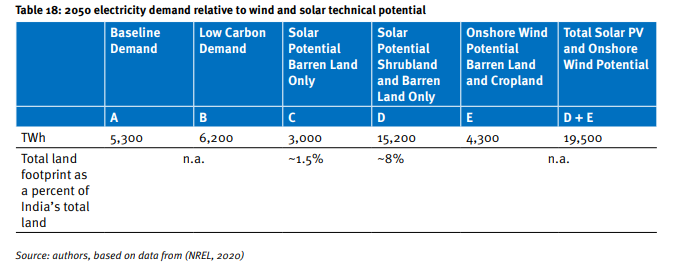

India is, simply put, a much poorer country than China. Its GDP at PPP is 57% below that of China. But I think this actually understates how far India is behind China.

Another way of looking: India's final energy consumption per capita is 70% below that of China.

India is, simply put, a much poorer country than China. Its GDP at PPP is 57% below that of China. But I think this actually understates how far India is behind China.

Another way of looking: India's final energy consumption per capita is 70% below that of China.

3/n

Even at PPP, China's final energy intensity of GDP is 30% higher than India's.

Why is this? Essentially, it boils down to economic structure 👇. China's industry share in GDP is much higher than India, and China's industry sector is more energy intensive.

Even at PPP, China's final energy intensity of GDP is 30% higher than India's.

Why is this? Essentially, it boils down to economic structure 👇. China's industry share in GDP is much higher than India, and China's industry sector is more energy intensive.

4/n

China's high industry, high investment economic model is tremendously resource-intensive. This is not just high-end, high-valued electronics manufacturing; it's good old cement and steel underpinning China's very high investment rate, which is not really falling either.👇

China's high industry, high investment economic model is tremendously resource-intensive. This is not just high-end, high-valued electronics manufacturing; it's good old cement and steel underpinning China's very high investment rate, which is not really falling either.👇

5/n

This brings us to the essential difference between China and India:

- China has largely built the physical foundations of a more or less developed economy (and then some!). Getting to zero is a question of cleaning up, not building green.

India's fundamentally different.

This brings us to the essential difference between China and India:

- China has largely built the physical foundations of a more or less developed economy (and then some!). Getting to zero is a question of cleaning up, not building green.

India's fundamentally different.

6/n

For India, the question is can you urbanize and industrialize without 'carbonizing'. China has already 'carbonized', it now faces a similar challenge to developed countries - 'decarbonization'.

India faces the challenge of 'non-carbonization'.

For India, the question is can you urbanize and industrialize without 'carbonizing'. China has already 'carbonized', it now faces a similar challenge to developed countries - 'decarbonization'.

India faces the challenge of 'non-carbonization'.

7/n

So how can India respond to this new move from China?

Answering this means assuming, as I guess China has done, that Biden wins in November. Supposing he does, then I think pressure will ratchet up on climate, including on India.

So three suggestions for India.

So how can India respond to this new move from China?

Answering this means assuming, as I guess China has done, that Biden wins in November. Supposing he does, then I think pressure will ratchet up on climate, including on India.

So three suggestions for India.

8/n

One) Do a serious, transparent and comprehensive long-term strategy. This can show what is and isn't possible, why India is different, and what is needed to do more. This is not a defensive document, it's India's best case for options, needs and red-lines.

One) Do a serious, transparent and comprehensive long-term strategy. This can show what is and isn't possible, why India is different, and what is needed to do more. This is not a defensive document, it's India's best case for options, needs and red-lines.

9/n

Two) Consider sectoral peaking, but not aggregate. India still has a lot of growth from hard-to-abate sectors like freight, aviation, cement, etc. Technologies are emerging, but they are uncertain. Aggregate peaking is too a risky commitment as of now.

Two) Consider sectoral peaking, but not aggregate. India still has a lot of growth from hard-to-abate sectors like freight, aviation, cement, etc. Technologies are emerging, but they are uncertain. Aggregate peaking is too a risky commitment as of now.

10/n

But could India offer peaks in certain sectors, where the mitigation pathway is clearer? Certainly in power and passenger transport this appears possible (even BP has India's oil demand peaking before 2050 in its BAU case). Timelines would need to be worked out.

But could India offer peaks in certain sectors, where the mitigation pathway is clearer? Certainly in power and passenger transport this appears possible (even BP has India's oil demand peaking before 2050 in its BAU case). Timelines would need to be worked out.

11/n

They may not be the same in all sectors where peaking, so one could consider 'sequential sectoral peaking'.

Three) Evolve a new climate diplomacy. With its new announcement China is drifting ever faster out of the category of 'developing countries'.

They may not be the same in all sectors where peaking, so one could consider 'sequential sectoral peaking'.

Three) Evolve a new climate diplomacy. With its new announcement China is drifting ever faster out of the category of 'developing countries'.

12/n

Traditionally, India has looked for rhetorical and procedural concessions: 'climate justice' in the Paris Agreement preamble, preservation of the Annex based system of differentiation, limitation of climate negotiations to the UNFCCC and no other fora.

Traditionally, India has looked for rhetorical and procedural concessions: 'climate justice' in the Paris Agreement preamble, preservation of the Annex based system of differentiation, limitation of climate negotiations to the UNFCCC and no other fora.

13/n

That boat has sailed, for better or worse, and the more China offers, the more untenable it will be. India's new strategy must differentiate it from China (shouldn't be hard after Galwan), which means accepting some differentiation within 'developing countries'.

That boat has sailed, for better or worse, and the more China offers, the more untenable it will be. India's new strategy must differentiate it from China (shouldn't be hard after Galwan), which means accepting some differentiation within 'developing countries'.

14/n

India needs to define and articulate much more pragmatic and practical demands on developed countries, including around financing, technology demonstration in the sectors where India cannot yet be confident of mitigation options, and so on.

India needs to define and articulate much more pragmatic and practical demands on developed countries, including around financing, technology demonstration in the sectors where India cannot yet be confident of mitigation options, and so on.

15/n

In sum, China's announcement speeds up the inevitable: India will become the 'largest developing country emitter', sooner or later.

This brings strategic pressure; India needs a solid case for what it can and can't do.

Domestic policy and diplomacy should react.

In sum, China's announcement speeds up the inevitable: India will become the 'largest developing country emitter', sooner or later.

This brings strategic pressure; India needs a solid case for what it can and can't do.

Domestic policy and diplomacy should react.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh