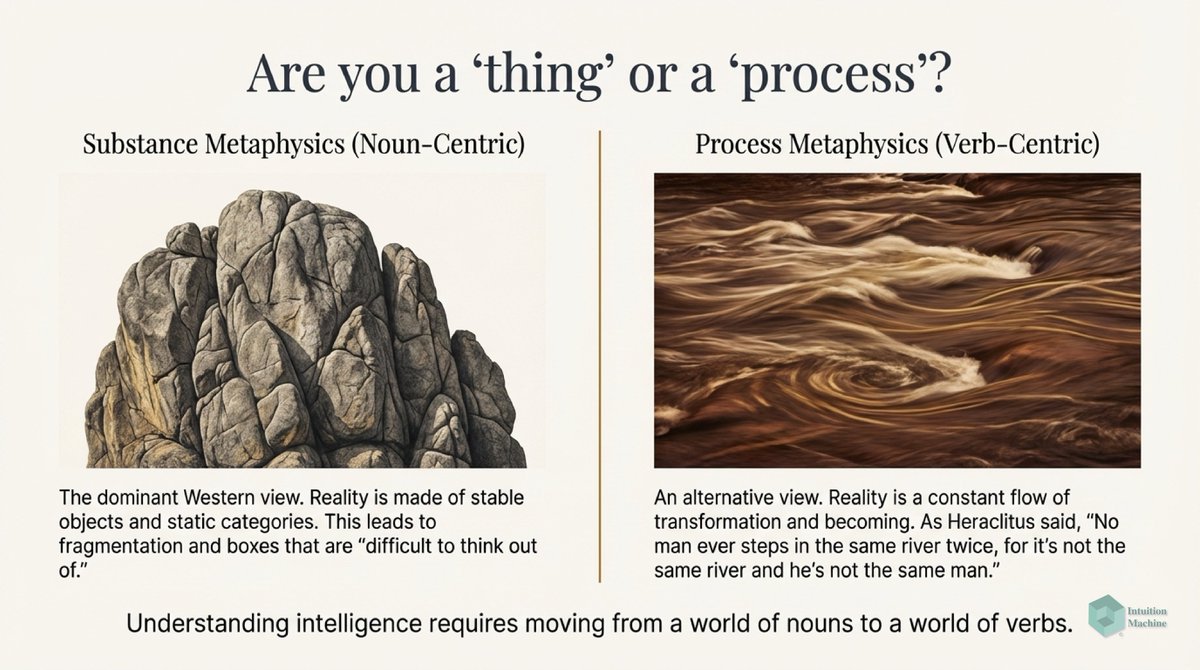

Amdahl's Law in parallel computing says that you can only have sub-linear speedup when converting a sequential algorithm to a parallel one. But, why does the massively parallel biological brain do perform so many operation with so little power?

It is universally true that if you convert a sequential algorithm into a parallel algorithm, the number of operations increases for the same problem. So how does a parallel brain do more with much less?

One way to reduce work is to not do any work at all! A brain does what it does because it avoids doing any work if it can. Call this the "lazy brain hypothesis".

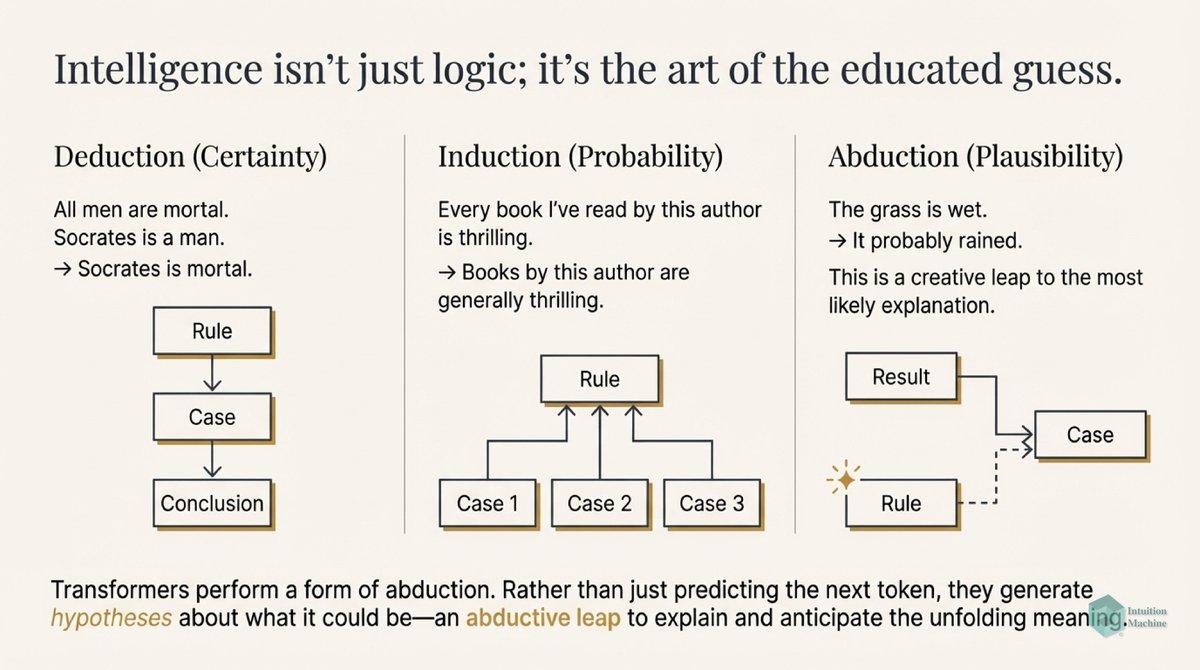

Most of what the brain performs is based on 'amortized inference'. In other words, behavioral shortcuts (or heuristics) that it has learned through experience and billions of years of evolutionary fine tuning.

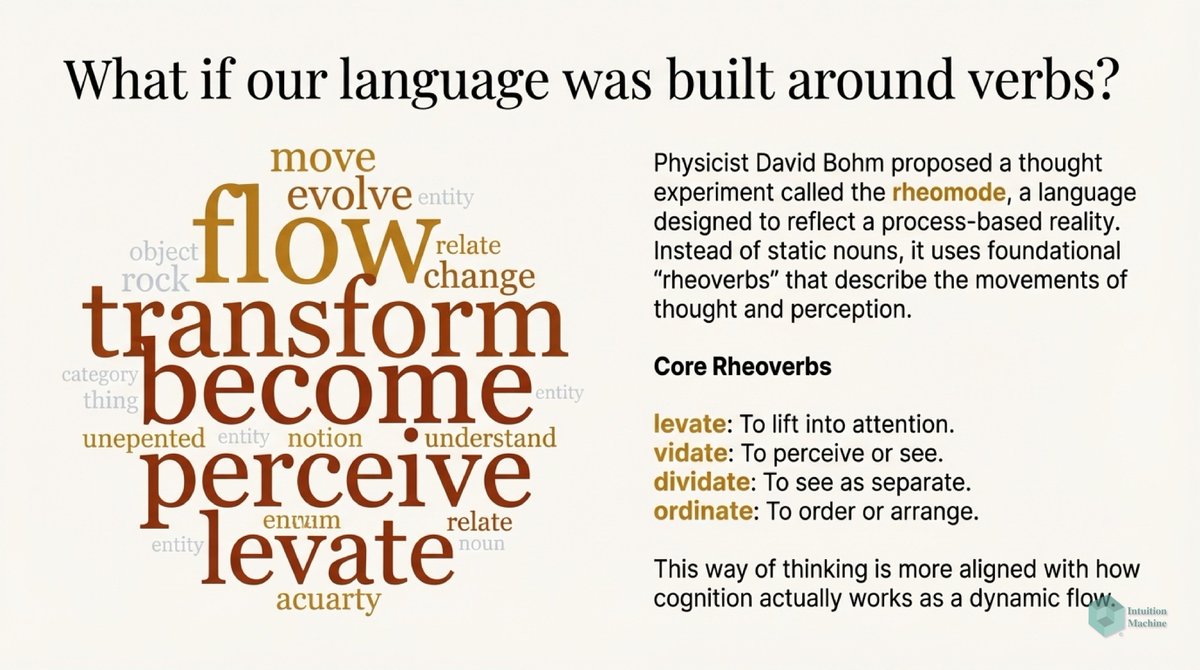

But what is the algorithm such it really doesn't do as little work at all? The lazy brain employs a lot of contextual information to make assumptions on what it's actually perceiving. In fact, it's isn't even bother to perceive. It just hallucinates what it sees.

It only fires up extra processing when it notices a discrepanancy in its expectations. We call this a surprise (which incidentally is similar to being horrified). It's a wakeup call for our consciousness to be engaged in more work.

So when it is in surprise, it is executing more threads to quickly discover knowledge to compensate for the discrepancy. But the first one that gets a match implies that all other threads are shutting down.

In short, the parallel process does not do all the work that a comparable sequential process does. The reason why this laziness is acceptable is that it only needs a good enough result and not the best result.

The massively parallel architecture of the brain allows for a massive number of threads to be executed, but most of these threads are terminated very early. But again, it is a mistake to think that all the threads are activated.

Only the threads that are related to the current context. Furthermore, all threads are automatically terminated withing a fixed period. But the brain still maintains longer ranged contexts because there are neurons that just happen to work at a very slow pace.

So we can think of a brain having parallel processes running at different speeds, all providing context to one another. All basically not doing much for most of the time.

But what does 'not doing much' actually mean? It means that the brain operates on its default mode with as little energy as possible. Anything outside the normal requires energy.

What's interesting is that our attention is controlled in the same way as motor actions (via the Basal Ganglia). Our attention navigates or feels its way just like your fingers feel its way while examining a fabric.

The brain does the laziest thing with attention, by inhibiting all information leading to the cortex by performing the filtering at the thalamus. So our cortex never perceives information that it is attending to. It simply isn't there to process.

So when we are focused in thought, we are always on a very narrow path of perception. Attention seems to counter the emersion in the world with all one's senses. To maximize our perception we dilute our focus. You can't attend to everything, at best you attend to nothing!

To engage wholely in this world, you avoid inhibiting your senses and that implies not attending to anything. It is in the same state as if you were in play.

However, when we are performing reason (i.e. system 2) our attention focuses on our thoughts. We are generating reason for our actions. We don't reason and then act, that's not the lazy way. We act, then we reason if we have to.

As we explore this lazy brain hypothesis, we begin to realize that our cognitive behavior works in a way that is the opposite of how we commonly think of it.

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh