2,499 years ago, approximately #OTD, the straits between the Greek mainland and the island of Salamis became the site of one of the most famous naval battles in history.

Have you ever wondered what actually happened? Follow @Roelkonijn and I for yet another thread 1/lots

Have you ever wondered what actually happened? Follow @Roelkonijn and I for yet another thread 1/lots

As you know from previous threads, the Persian forces had taken Themopylai and their navy had survived the battle at Artemision.

Xerxes’ forces moved south, through Boiotia and into Attika. Here they burned Athens and prepared to deal with the fleet moored at Salamis.

2/

Xerxes’ forces moved south, through Boiotia and into Attika. Here they burned Athens and prepared to deal with the fleet moored at Salamis.

2/

So, what did that Greek resistance look like?

For what is the most famous battle in Athenian history (on par only with Marathon), we must have some reliable information surely? Surely?!

NOPE!

3/

For what is the most famous battle in Athenian history (on par only with Marathon), we must have some reliable information surely? Surely?!

NOPE!

3/

Two main sources: Herodotus says 380 ships by the day of the battle, which is rather impressive.

Aeschylus says 300 or 310 ships - which one is it?

H says 180 ships were Athenian, same at Artemision, but this is unlikely as Athens had 90 ships disabled in that battle

4/

Aeschylus says 300 or 310 ships - which one is it?

H says 180 ships were Athenian, same at Artemision, but this is unlikely as Athens had 90 ships disabled in that battle

4/

When the Acropolis was burned, many Greek states fled. Those that remained were torn between fighting at Salamis (Athenians) V retreating to the C. Isthmus to defend the Peloponnese (everyone else)

Themistokles puts up a tactical argument for the narrow strait of Salamis.

5/

Themistokles puts up a tactical argument for the narrow strait of Salamis.

5/

His argument does not work!

So, he does the next best thing – he threatens them. Fight at Salamis or the Athenians will leave for Italy.

The commander, Eurybiades the Spartan (with 16 ships) panicked at losing the Athenians (50% of the whole fleet, between 110-200 ships!)

6/

So, he does the next best thing – he threatens them. Fight at Salamis or the Athenians will leave for Italy.

The commander, Eurybiades the Spartan (with 16 ships) panicked at losing the Athenians (50% of the whole fleet, between 110-200 ships!)

6/

For those keeping count. Yes, Sparta had seen what happened at Thermopylai, and Artemision, and gone:

‘Right, we need to take this more seriously, send … *counts fingers while muttering* … 6 more ships than last time!’

7/

‘Right, we need to take this more seriously, send … *counts fingers while muttering* … 6 more ships than last time!’

7/

The Greek alliance/resistance was hanging by a thread. Different states had different concerns, namely themselves!

It was only a matter of time before this all fell apart!

8/

It was only a matter of time before this all fell apart!

8/

Xerxes holds a meeting to plan what to do. His advisors say he should fight now. Artemisia is the voice of dissent, tells X there is no need to fight, the Greeks will self implode.

Do we trust this story? Not sure, but it gives a Greek idea of the Persian dilemma.

9/

Do we trust this story? Not sure, but it gives a Greek idea of the Persian dilemma.

9/

The battle begins with a convoluted conspiracy.

Themistokles worries the Peloponnesians want to flee, so he sends information to the Persians to encourage them to attack. This would then force all the Greeks to commit to battle.

10/

Themistokles worries the Peloponnesians want to flee, so he sends information to the Persians to encourage them to attack. This would then force all the Greeks to commit to battle.

10/

A Greek spy in the Persian camp then brings a message telling the Greeks that the Persians were planning to attack, and cut off the retreat.

Keeping up?

This comes to Themistokles, who of course already knew, and he passed it on . . . so Eurybiades jumps to action.

11/

Keeping up?

This comes to Themistokles, who of course already knew, and he passed it on . . . so Eurybiades jumps to action.

11/

Xerxes’ fleet repeats its plan at Artemision. A large contingent is sent to circumnavigate Salamis and cut off the escape route (entering the strait from the north, while the main fleet come from the south)

12/

12/

The Greeks sent the Corinthians to hold the northern part of the strait, and if necessary break through it to allow for an escape (Note: remember this for later! It’s important)

13/

13/

The Greeks made their sacrifices and read their omens. Phanias of Lesbos, makes the claim that the omens were interrupted by the arrival of Persian prisoners. The seer, Euphrantides, said they should be sacrificed to Dionysus Eater-of-Raw-Flesh.

Themistokles agreed.

14/

Themistokles agreed.

14/

It is probably not true, but not worth leaving out!

Plutarch, who records it in Life of Themistokles (13.2-3) was adamant that Phanias (student of Aristotle) was a reliable source of historical information . . . I will leave that for you to decide!

#HumanSacrifice #Debate

15/

Plutarch, who records it in Life of Themistokles (13.2-3) was adamant that Phanias (student of Aristotle) was a reliable source of historical information . . . I will leave that for you to decide!

#HumanSacrifice #Debate

15/

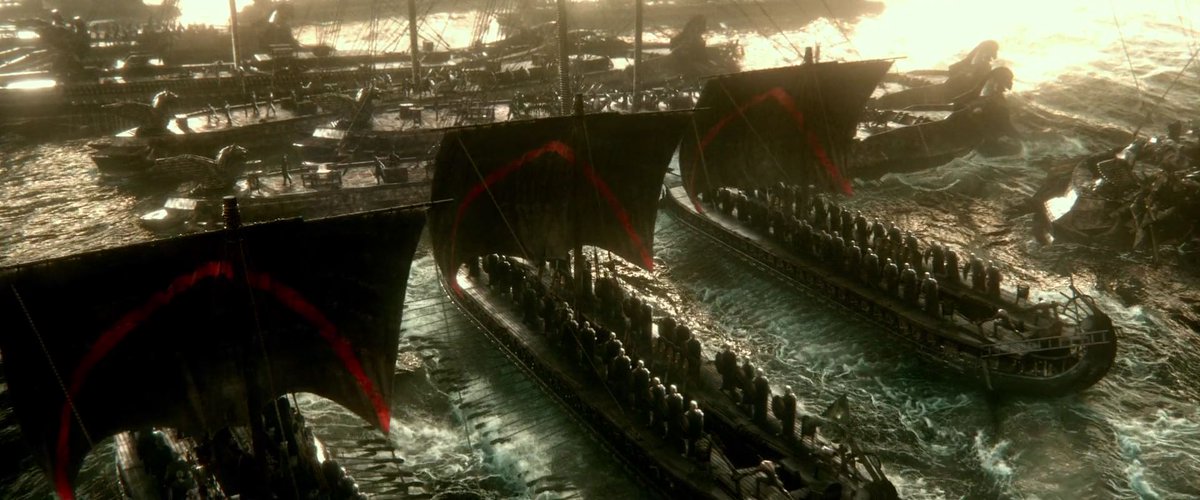

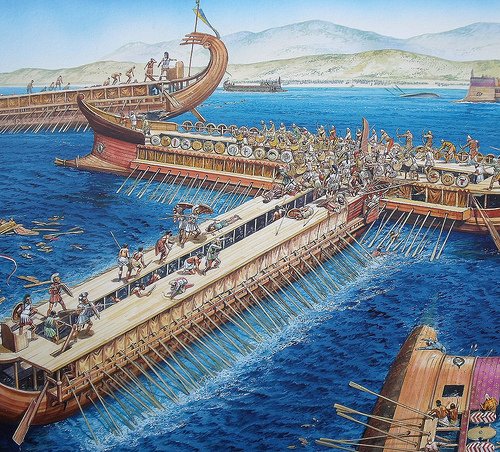

The Greeks sang their paean, and the trumpets soon blew loudly, signalling the fleet to set out and line up in the narrows.

The Persian fleet followed suit, but their lines had to adjust as they moved north through the strait.

16/

The Persian fleet followed suit, but their lines had to adjust as they moved north through the strait.

16/

With a disordered Persian line in front, the Athenians sailed head on into the Phoenicians. This was not a tactical battle, it was a slog. The Athenians fought hard and suffered heavy losses.

The rest of the Greeks . . . did nothing at this point. They kept backing water!

17/

The rest of the Greeks . . . did nothing at this point. They kept backing water!

17/

Except, that is, for the Corinthians (remember them? It’s important!).

They were fighting a superior Egyptian fleet to the north. To the Egyptians, these were minor skirmishes. For the Corinthians, this was an amazing and mammoth effort against all odds.

18/

They were fighting a superior Egyptian fleet to the north. To the Egyptians, these were minor skirmishes. For the Corinthians, this was an amazing and mammoth effort against all odds.

18/

Athenian successes, mixed with the ever-narrowing seascape, slowed the Persian advance, and filled the other Greeks’ hearts with courage.

They joined the fight, rowing hard and using their momentum to a distinct advantage.

19/

They joined the fight, rowing hard and using their momentum to a distinct advantage.

19/

The graphic scenes are harrowingly described by the eyewitness Aeschylus as he describes men falling into the sea and being skewered like fish by enemy spears.

This was not a scene of heroic glory. This was carnage, and the wine-dark sea turned a nasty shade of red that day.

20/

This was not a scene of heroic glory. This was carnage, and the wine-dark sea turned a nasty shade of red that day.

20/

The Persians try to turn and flee. In the confusion, Artemisia is chased down by Greek ships. She attacks an ally ship, creating the illusion she was Greek, and the Greek ships fall for it and abandon pursuit.

More fool them, there was a 10,000 drachmas bounty on her head!

21/

More fool them, there was a 10,000 drachmas bounty on her head!

21/

The battle was not over. The Persian fleet had dispersed, but they had a small land force on the island of Psyttaleia.

The Persians fought bravely, using arrows, then rocks, then hand to hand. But the Greeks killed each and every one of them.

22/

The Persians fought bravely, using arrows, then rocks, then hand to hand. But the Greeks killed each and every one of them.

22/

The Greeks prepared for day 2 of battle. They had not destroyed the Persian fleet, they were still in a precarious position!

But thankfully for them, day 2 never came.

23/

But thankfully for them, day 2 never came.

23/

As for Persia. They'd lost the battle but not the war. Xerxes returned home, as all Persian kings did after the first year of a campaign, + left command to his most senior general Mardonios.

He also left a strong land force, with instructions to mop up the Greek resistance.

24/

He also left a strong land force, with instructions to mop up the Greek resistance.

24/

Persian plans relied on the disunity of the Greeks. Even after Salamis, many Greek states remained on the Persian side. Nothing had really changed.

Salamis stopped Greece from falling in 480 BC. It did not stop the Persians from taking Greece altogether. The war waged on

25/

Salamis stopped Greece from falling in 480 BC. It did not stop the Persians from taking Greece altogether. The war waged on

25/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh