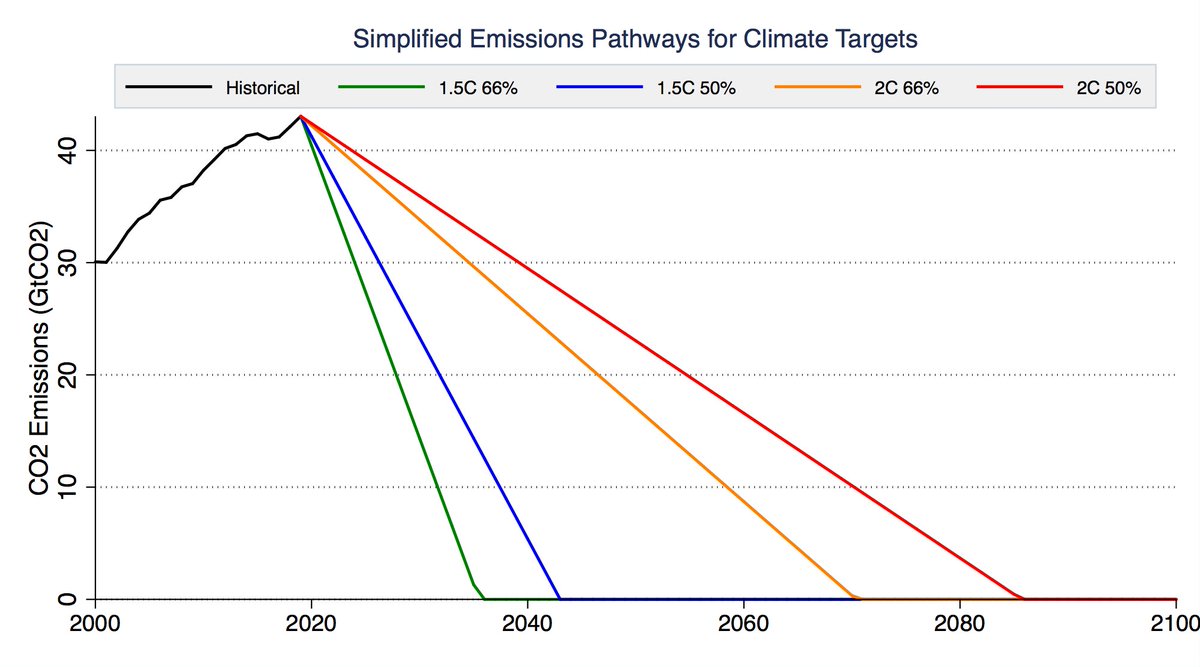

There is a lot of confusion about carbon budgets and how quickly emissions need to fall to zero to meet various warming targets. To cut through some of this morass, we can use some very simple emission pathways to explore what various targets would entail. 1/11

Much confusion is due to ambiguity of these targets, role of negative emissions, non-CO2 forcings, historical warming, etc. For example, "well-below" 2C target in the Paris Agreement is often interpreted to mean a 66% chance of avoiding >2C warming. carbonbrief.org/analysis-why-t… 2/11

On the other hand, the 1.5C aspirational target is sometimes defined as a 50% chance of limiting warming to 1.5C, and sometimes (as in the new SSP1-1.9 scenario) as a 66% chance of avoidance. 3/11

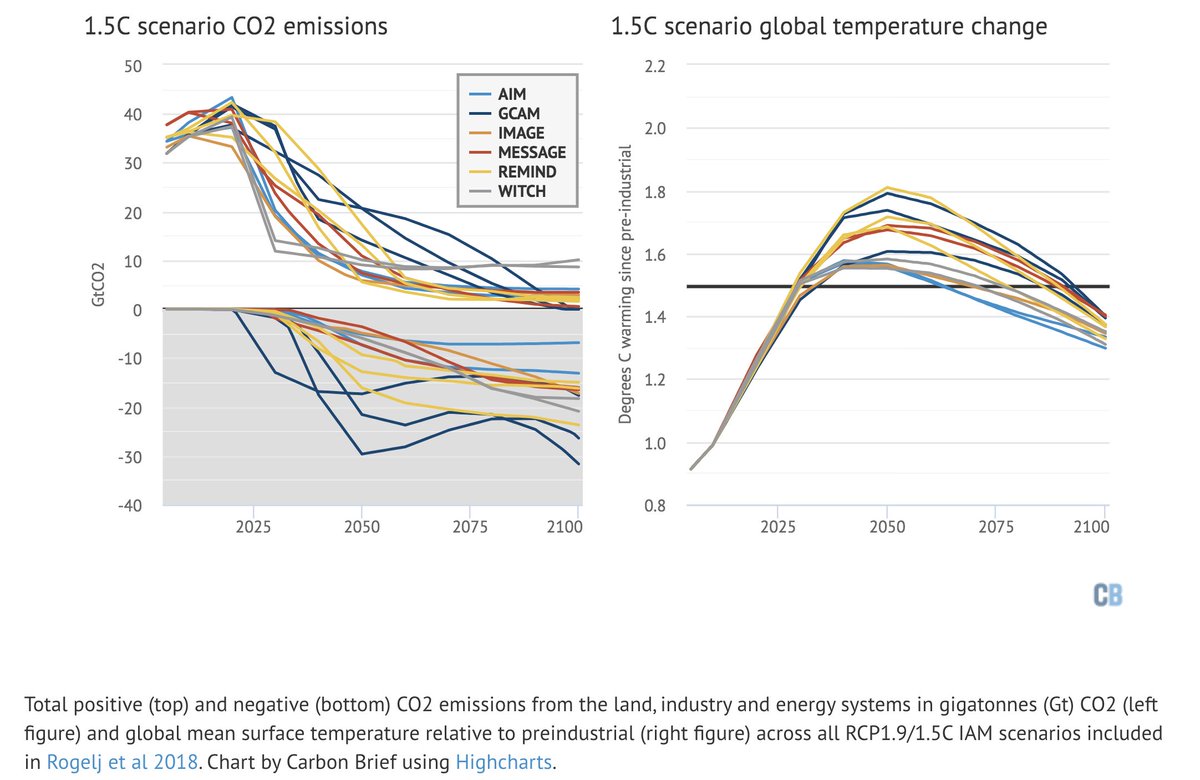

Virtually all scenarios use negative emissions to expand the allowable budget; in the SSP 1.5C scenarios negative emissions effectively increases the size of the 420 GtCO2 budget by between 90% and 380%, allowing positive emissions of between 800 and 1600 GtCO2 by 2100 4/11

But leaving aside negative emissions (and their moral hazards) for the moment, the carbon budgets in the IPCC SR15 report make it relatively simple to calculate when emissions would have to reach zero under different climate targets: 5/11

If we assume that emissions simply linearly decrease until they reach zero, and look at four different interpretations of climate targets (66% chance of < 1.5C, 50% of < 1.5C, 66% of < 2C, 50% of < 2C), we get the figure below: 6/11

To have a 66% chance of avoiding 1.5C warming, emissions would have to fall 66% by 2030 and reach zero by 2036. For a 50% chance of 1.5C its a 46% reduction by 2030 and zero by 2043. For 2C 66% (50%) its 21% (16%) reduction by 2030 and zero by 2071 (2085). 7/11

However, these climate model-based budgets do not account for some earth system feedbacks from melting permafrost and methane released from wetlands. The SR15 suggests that including these would reduce all the carbon budgets by around 100 GtCO2. Here is what that looks like: 8/11

In this case to achieve a 66% (50%) chance of avoiding 1.5C, emissions would have to fall 92% (57%) by 2030 and reach zero by 2031 (2039). For a 66% (50%) chance of avoiding 2C warming we'd have to reduce emissions 24% (18%) by 2030 and reach zero in 2066 (2082). 9/11

One big takeaway from these simplified emission pathways is that limiting warming to 1.5C in the absence of planetary-scale negative emissions would be extremely difficult, requiring full decarbonization of the global economy in the next two decades. 10/11

At the same time, the pathways for limiting warming to <2C are much more forgiving, avoiding the need to bet the future on somewhat magical thinking around negative emissions deployment. 11/11

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh