<THREAD>

SOME NOTES ON BIBLICAL WEIGHTS AND MEASURES.

Below, a five mina weight-stone from commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/,

where 𒈠𒈾 = «ma-na» = ‘mina’.

SOME NOTES ON BIBLICAL WEIGHTS AND MEASURES.

Below, a five mina weight-stone from commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/,

where 𒈠𒈾 = «ma-na» = ‘mina’.

MONEY

Money has been in use in the Near East for many millennia.

The most widely-used form of money/currency was silver, which is known to have been in use since at least the 3rd mill. BC.

Money has been in use in the Near East for many millennia.

The most widely-used form of money/currency was silver, which is known to have been in use since at least the 3rd mill. BC.

Gold enters the picture only much later, towards the end of the 2nd mill. (Powell 1996, Eshel 2019),

and coins later still, towards the end of the 1st mill. (Snell 1995:1496, Van der Spek 2015).

and coins later still, towards the end of the 1st mill. (Snell 1995:1496, Van der Spek 2015).

The Bible reflects a similar progression.

As soon as its record of the ANE begins, money is involved. (Abraham receives money from the king of Egypt, and buys a field from a Hittite in Canaan: cp. Gen. 12ff.)

As soon as its record of the ANE begins, money is involved. (Abraham receives money from the king of Egypt, and buys a field from a Hittite in Canaan: cp. Gen. 12ff.)

And most transactions in the early stages of the Biblical narrative (c. 70% of them) are paid in silver.

Gold isn’t mentioned as a form of payment until the time of David, i.e., until the turn of the 1st millennium (cp. 1 Chr. 21).

And coins enter the picture only in the New Testament (e.g., Matt. 22.19).

And coins enter the picture only in the New Testament (e.g., Matt. 22.19).

Of interest for a similar reason are the Bible’s references to ‘refined silver’.

The use of adulterated silver (mixed with copper) became a major issue in Canaan over the period 1200-1000 BC, after which time it ceased (Eshel 2019).

The use of adulterated silver (mixed with copper) became a major issue in Canaan over the period 1200-1000 BC, after which time it ceased (Eshel 2019).

That the Bible’s (only) references to refined silver relate to the time of David and Solomon (1 Chr. 29.4, Psa. 12.6) therefore makes good sense.

——————————————

——————————————

WEIGHTS

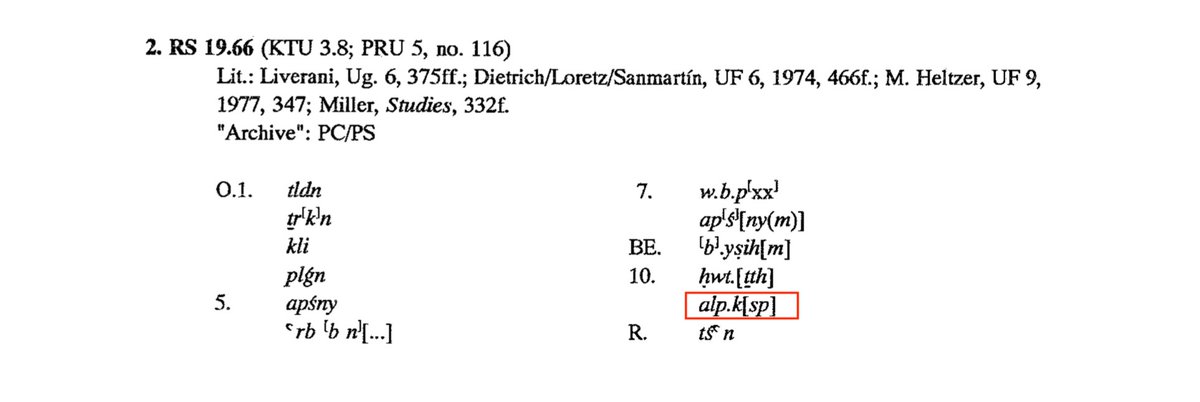

The basic unit of weight in the ANE was the ‘shekel’, as one would expect given the word’s etymology («šql» = ‘weight’).

As a result, the shekel functions as a default unit in ANE transactions.

The basic unit of weight in the ANE was the ‘shekel’, as one would expect given the word’s etymology («šql» = ‘weight’).

As a result, the shekel functions as a default unit in ANE transactions.

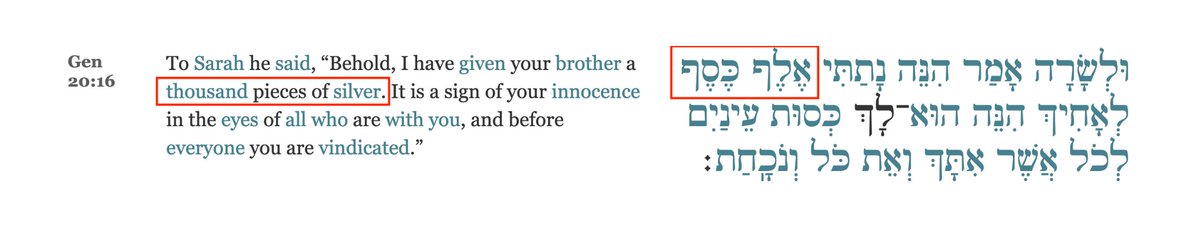

For instance, in the text below, the phrase «alp ksp» signifies «alp ṯql ksp» = ‘a thousand shekels of silver’.

(A thousand minas would be too much, and a thousand gerahs too little.)

(A thousand minas would be too much, and a thousand gerahs too little.)

The shekel is also omitted from certain payments of silver in the Biblical narrative.

Indeed, it is omitted from the very first payment recorded in the Biblical narrative (which exactly mirrors the Ugaritic tablet above):

Indeed, it is omitted from the very first payment recorded in the Biblical narrative (which exactly mirrors the Ugaritic tablet above):

As time goes on, however, the omission of the shekel becomes less common.

It is omitted three times in Genesis (Gen. 20.16, 37.28, 45.22),

three times in Joshua and Judges (Jos. 24.32, Judg. 9.4, 16.5),

twice in Kings (2 Kgs. 5.5, 6.25.),

and not thereafter,

It is omitted three times in Genesis (Gen. 20.16, 37.28, 45.22),

three times in Joshua and Judges (Jos. 24.32, Judg. 9.4, 16.5),

twice in Kings (2 Kgs. 5.5, 6.25.),

and not thereafter,

...all of which makes good sense.

In the era of the Kings, the mina and the talent start to be mentioned in the Biblical narrative (e.g., 1 Kgs. 10.17, 16.24), so the shekel needs to be specified explicitly.

——————————————

In the era of the Kings, the mina and the talent start to be mentioned in the Biblical narrative (e.g., 1 Kgs. 10.17, 16.24), so the shekel needs to be specified explicitly.

——————————————

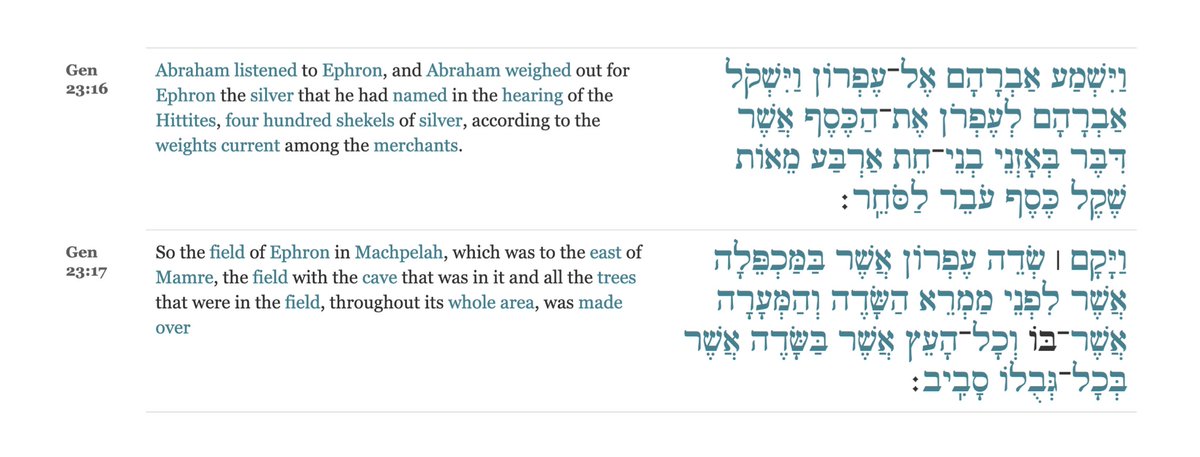

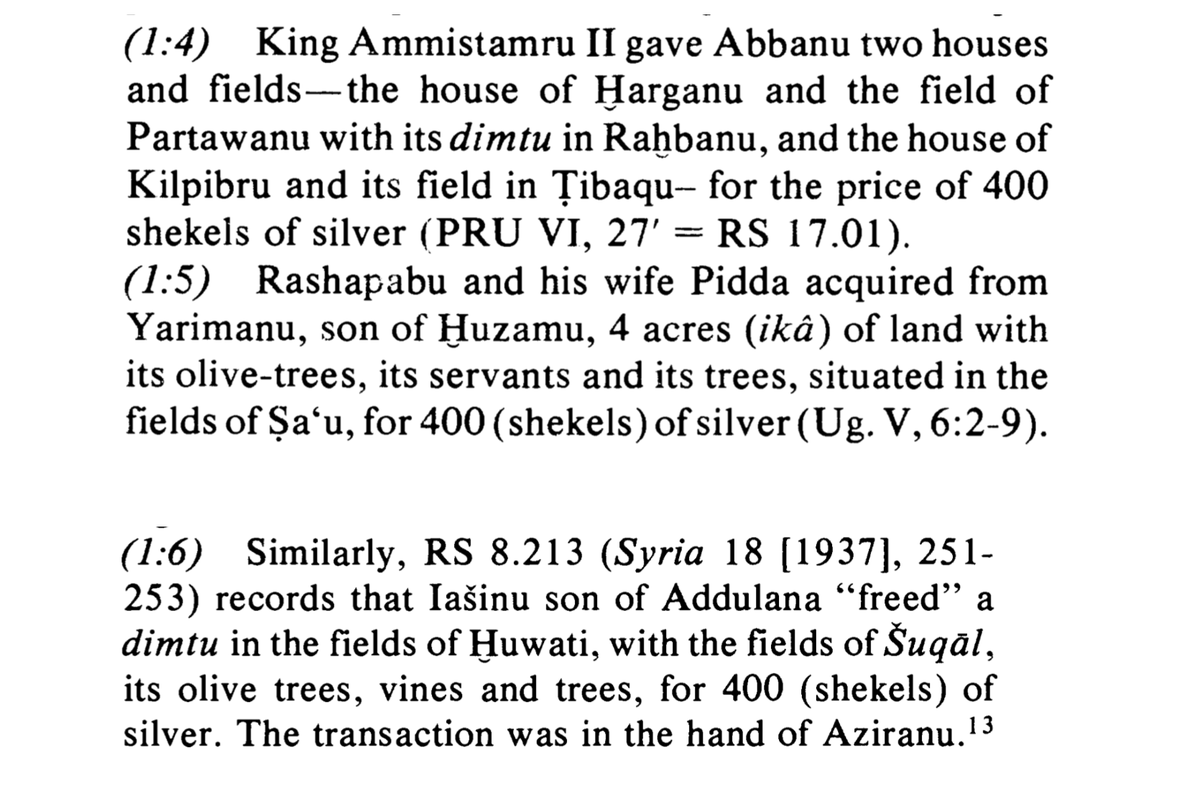

EPHRON THE HITTITE

The first *sale* mentioned in the Biblical narrative occurs in Gen. 23.

Abraham buys a field from a man known as ‘Ephron the Hittite’ for 400 shekels of silver—a weight/price which is said to be ‘current among the merchants’ (שקל כסף עֹבֵר לַסֹּחֵר):

The first *sale* mentioned in the Biblical narrative occurs in Gen. 23.

Abraham buys a field from a man known as ‘Ephron the Hittite’ for 400 shekels of silver—a weight/price which is said to be ‘current among the merchants’ (שקל כסף עֹבֵר לַסֹּחֵר):

What is signified by a weight which is ‘current among the merchants’ (עֹבֵר לַסֹּחֵר) is not immediately apparent.

Some take it to refer to an ‘international standard’ (Hurowitz 2000),

which is entirely possible.

Some take it to refer to an ‘international standard’ (Hurowitz 2000),

which is entirely possible.

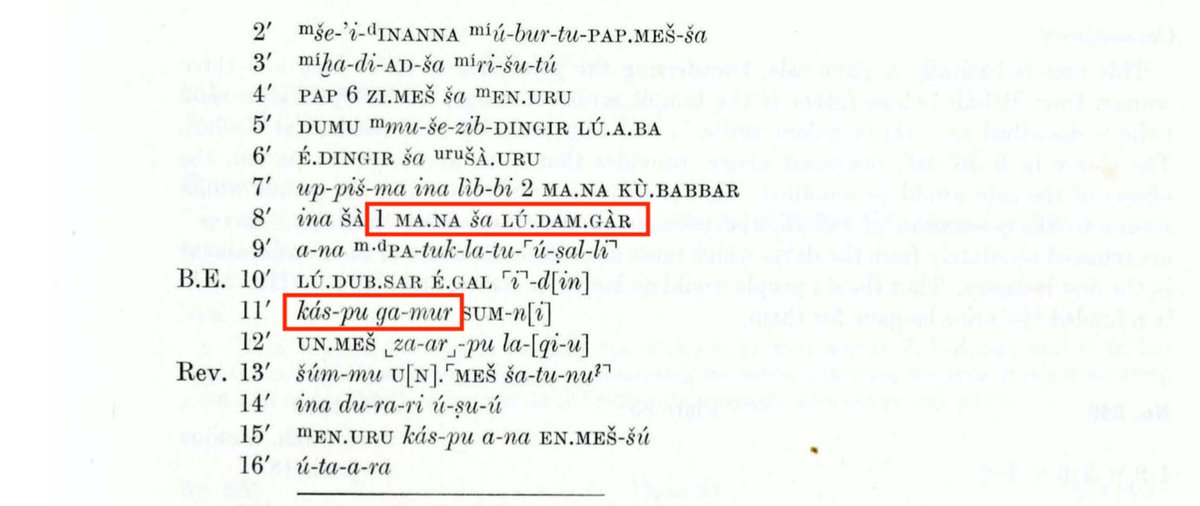

It strikes me, however, as very reminiscent of various Assyrian records of sales (such as the one below),

where the phrase ‘measured with the mina of the merchant’—i.e., ina ŠÀ 1 MA.NA ša LÚ.DAM.GÀR—is taken to mean ‘paid for with silver weighed on the spot’ (Fales 1996:15),

…which is precisely what happens in Gen. 23.

…which is precisely what happens in Gen. 23.

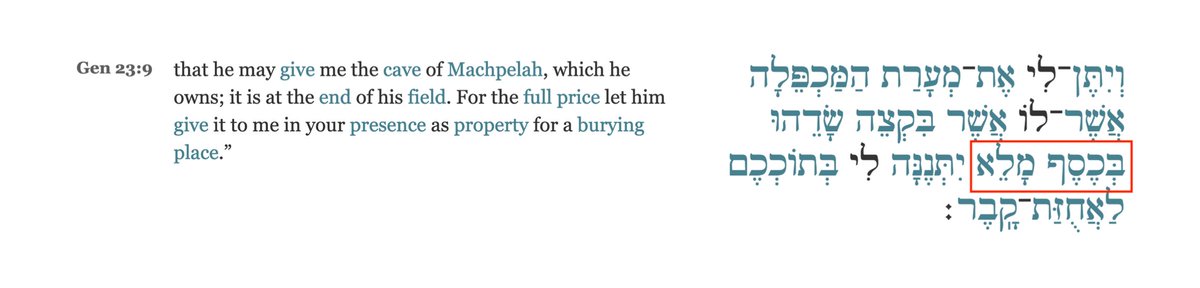

Note also the similarity between the Assyrian text’s reference to «kás-pu ga-mur» = ‘full price’ (L11’) and Gen. 23’s reference to כסף מָלֵא.

Ephron’s specific turn of phrase in 23.15 also deserves careful consideration.

Ephron refers to his field as אֶרֶץ ארבע מֵאֹת שֶֽׁקֶל־כֶּסֶף, i.e., ‘a 400-shekel plot of land’,

as if to suggest 400 shekels was a standardly-exchanged sum of money in the context of land sales.

Ephron refers to his field as אֶרֶץ ארבע מֵאֹת שֶֽׁקֶל־כֶּסֶף, i.e., ‘a 400-shekel plot of land’,

as if to suggest 400 shekels was a standardly-exchanged sum of money in the context of land sales.

Might, therefore, the sum of 400 shekels have been a kind of standard price associated with a particular/known area of land?

Over the years, a number of weight-stones without any marks/inscriptions to signify their weight have been discovered in Israel,

Over the years, a number of weight-stones without any marks/inscriptions to signify their weight have been discovered in Israel,

two of which in particular have caught the attention of archeologists because they are unusually heavy and weigh 400 shekels (Bashan 2006:706).

One of them is shown below:

One of them is shown below:

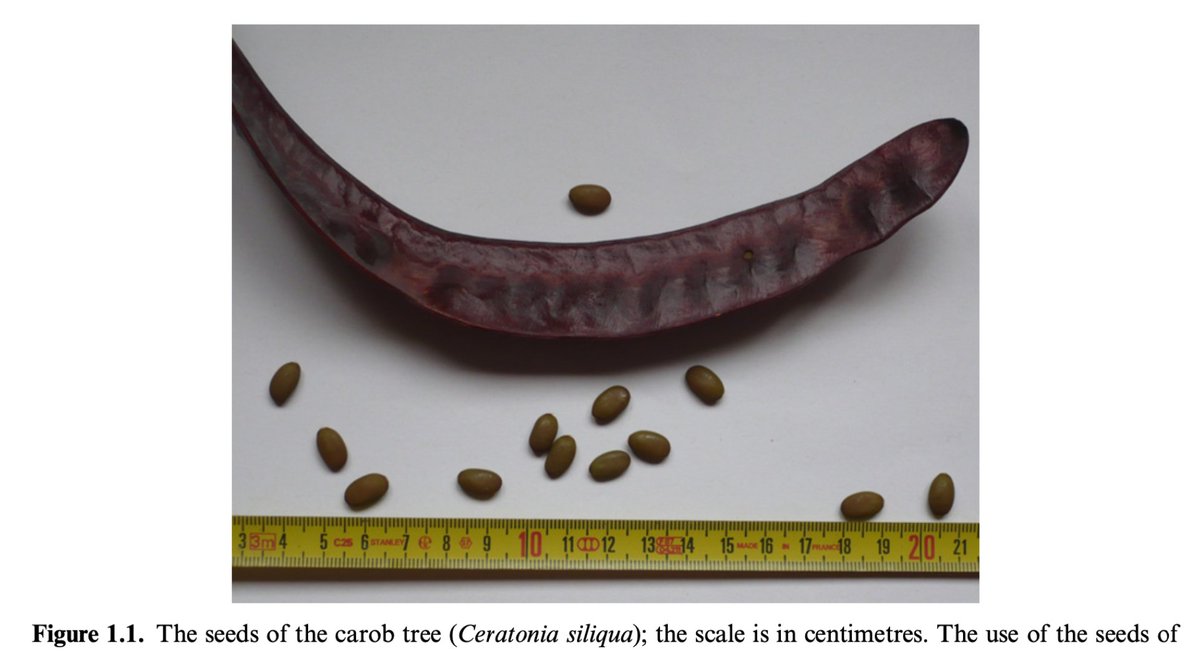

And at least three fields in Ugarit are known to have changed hands for the price of 400 shekels of silver.

…which seems especially noteworthy in light of the similarities between the description of these sales (‘a field, its trees, its vines…’) and the text of Gen. 23 (‘a field, its cave, its trees…’):

Also noteworthy is the text of Gen. 33, where Jacob (Abraham’s grandson) buys a plot of land near Shechem for 100 ‘kesitah’ (קשיטה).

The term ‘kesitah’ is not a common one. It’s attested only here in Gen. 33 and in Job 42.11, where it’s loosely connected with gold (cp. for context Gen. 24.22).

Might 100 kesitah also amount to 400 shekels?

Might 100 kesitah also amount to 400 shekels?

The silver-to-gold exchange rate in Ugarit is known to have been 4:1 in the case of high quality gold, i.e., «ḫrṣ»-gold (cp. UT 2101:20), so the idea doesn’t seem an implausible one.

The noun ‘kesitah’ (קשיטה) may even derive from a semantically similar root to the adjective «ḫrṣ» (‘high quality’), since the Arabic «QŚṬ» (قسط) and the Semitic root «ḪRṢ» belong to the same basic semantic domain (‘to separate, ajudge, exercise justice’).

———————————

———————————

OTHER FORMS OF CURRENCY

Many other forms of currency are mentioned in the Bible.

One is the ‘bekah’ (בקע).

Like the kesitah, the bekah appears to be a very ancient form of currency.

As such, little is known about it.

Many other forms of currency are mentioned in the Bible.

One is the ‘bekah’ (בקע).

Like the kesitah, the bekah appears to be a very ancient form of currency.

As such, little is known about it.

It’s mentioned only in Gen. 24, where Abraham’s servant gives Rebekah a gold ring which weighs half a bekah,

and in Exod. 38, where the Israelites take a census.

and in Exod. 38, where the Israelites take a census.

Petrie thinks the ‘beka’ was a very ancient unit of weight, and has found evidence of its use in the exchange of gold in 4th mill. Egypt (Petrie 1926).

which would certainly explain the distribution of the term ‘beka’ in the Biblical narrative.

——————————————

which would certainly explain the distribution of the term ‘beka’ in the Biblical narrative.

——————————————

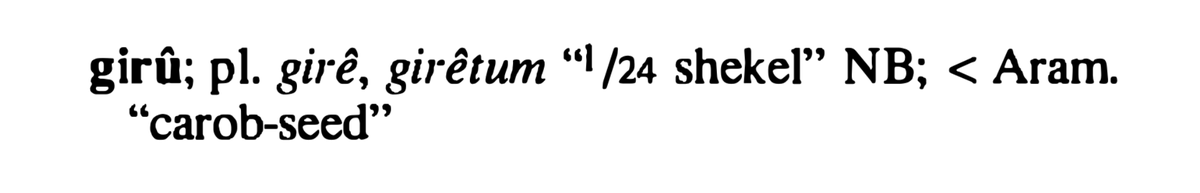

GERAHS

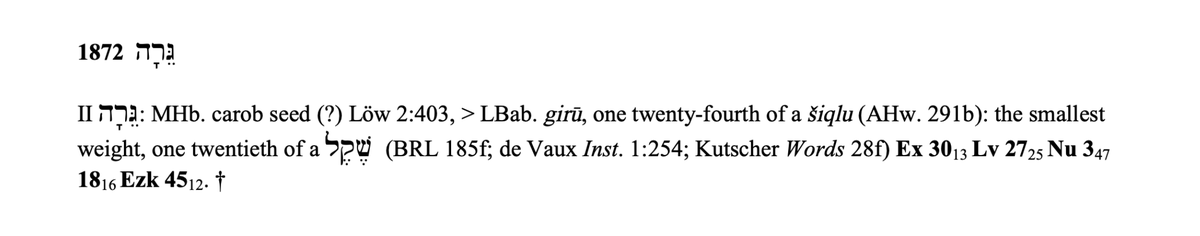

A better known Biblical unit of weight is the ‘gerah’ (גרה).

A better known Biblical unit of weight is the ‘gerah’ (גרה).

In most ancient civilisations, the smallest measure of length was based on a seed/grain:

for instance, in Sumeria, the ‘finger-width’ was defined as a unit equal to ‘six seeds’ (as it still is in some modern-day Islamic societies) (Williams 2020:1.2–3).

for instance, in Sumeria, the ‘finger-width’ was defined as a unit equal to ‘six seeds’ (as it still is in some modern-day Islamic societies) (Williams 2020:1.2–3).

Small units of *currency* in the ANE also appear to have seed/grain-related etymologies. In Mesopotamia, for instance, the second smallest unit of currency was the ‘giru’ (‘carob-seed’),

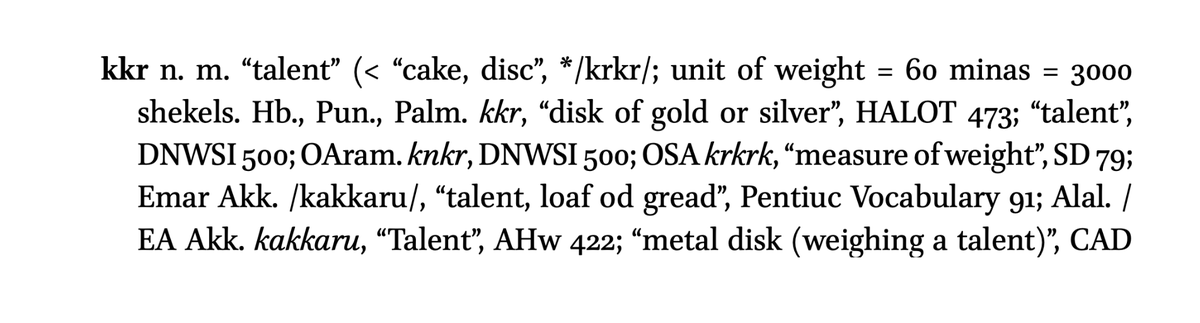

MINAS AND TALENTS

Another well-known measure of weight is the ‘mina’ (מנה).

While the shekel is mentioned frequently in the Biblical narrative, the mina is not.

It’s mentioned just once in the entirety of Genesis through to the end of Kings/Chronicles (in 1 Kgs. 10).

Another well-known measure of weight is the ‘mina’ (מנה).

While the shekel is mentioned frequently in the Biblical narrative, the mina is not.

It’s mentioned just once in the entirety of Genesis through to the end of Kings/Chronicles (in 1 Kgs. 10).

Thereafter, the mina is mentioned only in Ezekiel (in the context of Ezekiel’s temple),

in Ezra and Nehemiah (the silver brought back from Babylon by the exiles is weighed in minas),

and in Jesus’ parable (Luke 19).

in Ezra and Nehemiah (the silver brought back from Babylon by the exiles is weighed in minas),

and in Jesus’ parable (Luke 19).

As such, the Bible’s references of minas fit the pattern of Ugaritic literature, where shekels and talents are frequently referred to, but references to mina are few and far between (Zaccagnini 1979:472).

Note: I intend to pester @lettlander to provide me with evidence to prove/disprove this claim. Please ‘like’ this tweet in order to encourage him to do so.

——————————————

——————————————

THE MINA AND GEOGRAPHY

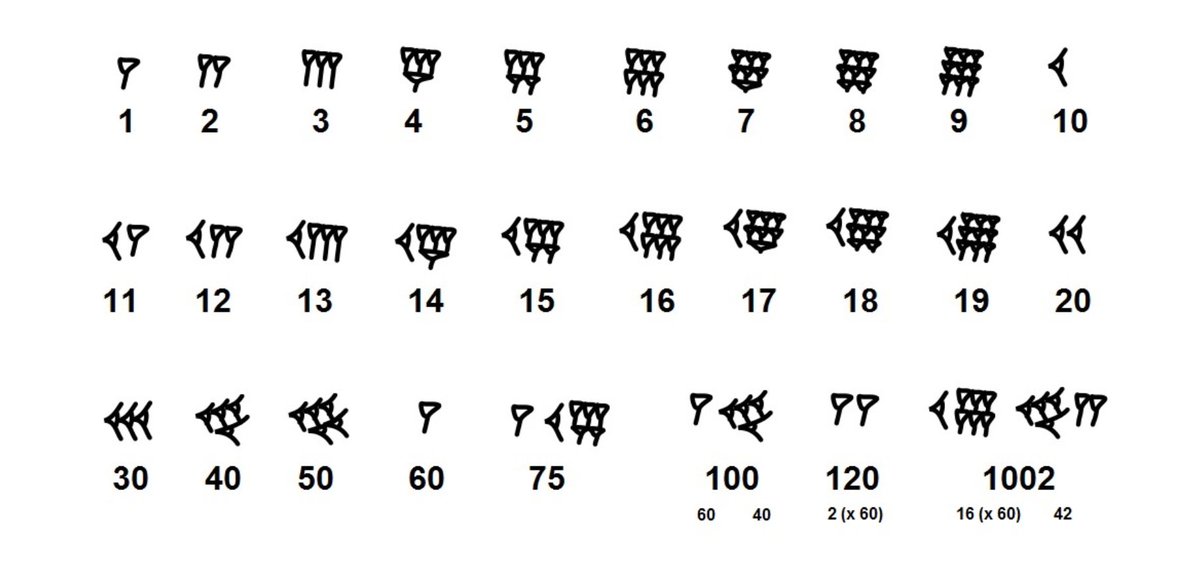

Much to metrologists’ frustration, the ANE doesn’t have a standardised definition of a mina.

The make-up of the mina differs from nation to nation.

In ancient Mesopotamia, it was composed of 60 shekels,

Much to metrologists’ frustration, the ANE doesn’t have a standardised definition of a mina.

The make-up of the mina differs from nation to nation.

In ancient Mesopotamia, it was composed of 60 shekels,

Consequently, a Mesopotamian ‘talent’ (‘biltu’) was equivalent to 60 x 60 = 3,600 shekels.

In Exod. 38, however, a ‘talent’ (‘kikkar’) is implied to consist of 3,000 shekels:

In Exod. 38, however, a ‘talent’ (‘kikkar’) is implied to consist of 3,000 shekels:

Consider the mathematics (for non-English speakers, ‘math’) of the above passage.

603,550 men each contribute half a shekel to the Tabernacle,

which amounts to a total of 100 talents and 1,775 shekels.

We hence obtain the equation 100 * V(talent) + 1,775 = 603,550 / 2,

603,550 men each contribute half a shekel to the Tabernacle,

which amounts to a total of 100 talents and 1,775 shekels.

We hence obtain the equation 100 * V(talent) + 1,775 = 603,550 / 2,

which means the value of a talent must be 3,000 shekels.

As such, the talent of Exodus 38 is the same as that of Syria/Canaan in the 2nd mill. BC more generally (Zaccagnini 1979), e.g., in Ugarit:

As such, the talent of Exodus 38 is the same as that of Syria/Canaan in the 2nd mill. BC more generally (Zaccagnini 1979), e.g., in Ugarit:

Two possibilities thus emerge: either a] a talent consists of fifty 60-shekel minas, or b] a talent consists of sixty 50-shekel minas.

Of these possibilities, the latter strikes me as the more likely. Here’s why.

Of these possibilities, the latter strikes me as the more likely. Here’s why.

‘Round numbers’ tend to reflect a unit’s subdivisions.

For instance, because a week consists of 7 days, it’s natural to talk about a period of 14 days, generally as an estimate.

And, because a year consists of 12 months, it’s natural to talk about 6 months, 18 months, etc.

For instance, because a week consists of 7 days, it’s natural to talk about a period of 14 days, generally as an estimate.

And, because a year consists of 12 months, it’s natural to talk about 6 months, 18 months, etc.

The same is true of other measurements and estimates (e.g., 6 inches, 12 ounces, 50 metres, etc.).

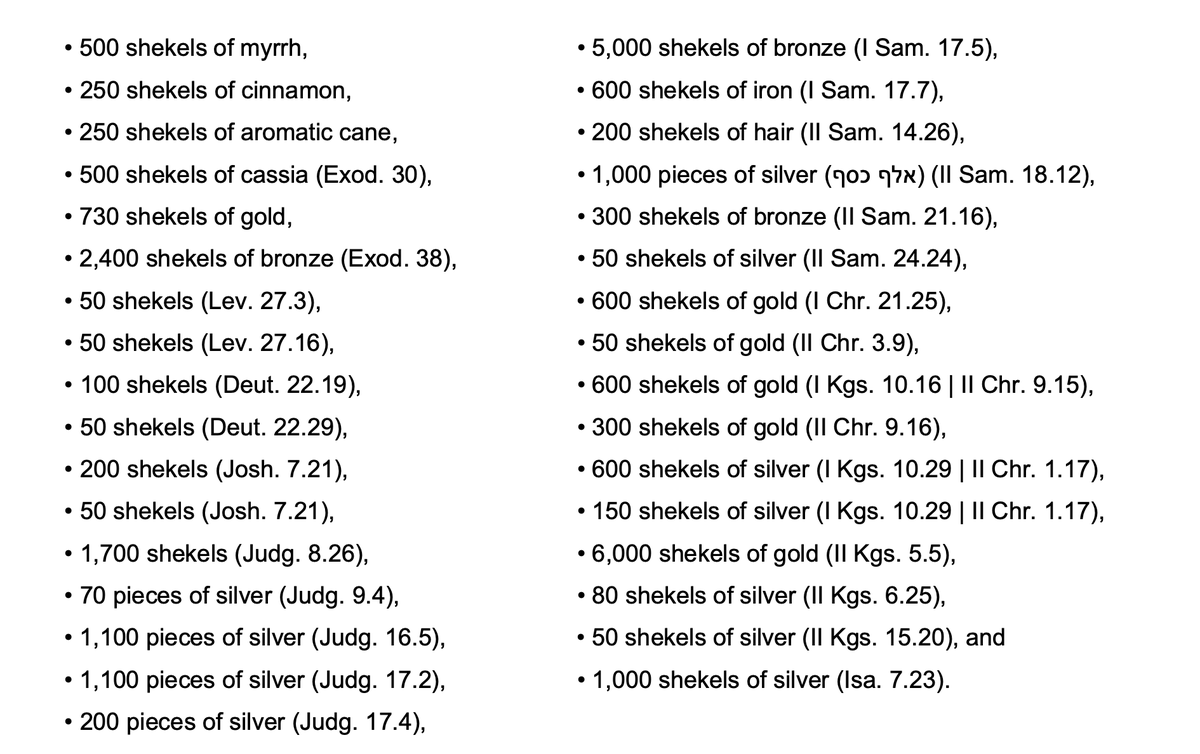

Consequently, references to large numbers of shekels in the Biblical narrative may be able to help us determine whether Israel’s mina was composed of 50 or 60 shekels.

Consequently, references to large numbers of shekels in the Biblical narrative may be able to help us determine whether Israel’s mina was composed of 50 or 60 shekels.

After all, where weights are concerned, ‘round numbers’ are not merely a concept. Weights have to be weighed out.

And to weigh out, say, 50 shekels of gold given only a collection of single-shekel weight-stones and a 60-shekel weight-stone would be a nuisance,

And to weigh out, say, 50 shekels of gold given only a collection of single-shekel weight-stones and a 60-shekel weight-stone would be a nuisance,

…while to weigh out 50 shekels of gold given a 50-shekel weight-stone would be very easy.

Consider, then, the Bible’s references to weights of 50 shekels or more from the time of the exodus onwards:

Consider, then, the Bible’s references to weights of 50 shekels or more from the time of the exodus onwards:

To my mind, these weights seem far more at home in a decimal than a sexagesimal system.

Note by way of demonstration the points below:

Note by way of demonstration the points below:

🔹 The most commonly attested weight in the Biblical narrative is ‘50 shekels’ (attested seven times), which is as one would expect if the Biblical narrative reflects a society whose mina was composed of 50 shekels.

🔹 Only 25% of the weights above are divisible by 60 (or 30).

🔹 Only 25% of the weights above are divisible by 60 (or 30).

🔹 Over 90% of the weights above are exactly divisible by 50.

🔹 The weights in the Biblical narrative which aren’t divisible by 50 (namely 730 shekels, 70 shekels, and 80 shekels) aren’t divisible by 60 either,

🔹 The weights in the Biblical narrative which aren’t divisible by 50 (namely 730 shekels, 70 shekels, and 80 shekels) aren’t divisible by 60 either,

in which case they don’t ultimately favour a 50 *or* a 60 based system; indeed, they are not ‘lump sums of money’ at all:

730 shekels is the total weight of the gold used in the sanctuary’s construction (Exod. 38);

730 shekels is the total weight of the gold used in the sanctuary’s construction (Exod. 38);

70 shekels is the total price paid by Abimelech to hire 70 men at the rate of a shekel per head (Judg. 9.4);

and 80 shekels is the hyper-inflated value of a donkey’s head in the days of the siege of Samaria,

and 80 shekels is the hyper-inflated value of a donkey’s head in the days of the siege of Samaria,

and may be a notional/illustrative sum rather than one which was actually paid (2 Kgs. 6.25).

Like that of her Semitic neighbours in the 2nd mill., then, Israel’s mina seems to have consisted of 50 shekels.

Like that of her Semitic neighbours in the 2nd mill., then, Israel’s mina seems to have consisted of 50 shekels.

A similar conclusion can be drawn from the text of 1 Kgs. 10.17.

The text of 1 Kgs. 10.17 refers to ‘three minas’ of gold, which 2 Chr. 9.16 equates with 300 shekels.

The text of 1 Kgs. 10.17 refers to ‘three minas’ of gold, which 2 Chr. 9.16 equates with 300 shekels.

At first blush, that might lead us to think Israel’s mina was composed of 100 shekels (contra all known ANE conventions).

The text of 2 Chr. 9 is, therefore, frequently dismissed as errant/corrupt.

The text of 2 Chr. 9 is, therefore, frequently dismissed as errant/corrupt.

But a more careful consideration of the text reveals a more complex and coherent situation.

As we’ve already noted, 1 Kgs. 10.17’s reference to a mina is unusual. It’s the only Biblical reference to a mina in the entire Biblical narrative from the exodus through to the exile.

Why, then, does our author mention a mina here in 1 Kgs. 10 and not elsewhere?

Why, then, does our author mention a mina here in 1 Kgs. 10 and not elsewhere?

One possibility, which strikes me as a plausible one, is as follows:

because 1 Kgs. 10.17 doesn’t refer to a normal mina; it refers to a ‘heavy mina’ (a well-established notion in the ANE),

which explains the higher-than-expected weight quoted in 2 Chr. 9.

because 1 Kgs. 10.17 doesn’t refer to a normal mina; it refers to a ‘heavy mina’ (a well-established notion in the ANE),

which explains the higher-than-expected weight quoted in 2 Chr. 9.

Furthermore, it explains the specific figure quoted in 2 Chr. 9,

since the heavy mina was typically twice the weight of the standard mina (Fales 1996:12, Kletter 2002:249–250),

in which case, per the claim of 2 Chr. 9, three heavy minas would amount to 300 shekels (3 x 50 x 2).

since the heavy mina was typically twice the weight of the standard mina (Fales 1996:12, Kletter 2002:249–250),

in which case, per the claim of 2 Chr. 9, three heavy minas would amount to 300 shekels (3 x 50 x 2).

The text of 1 Kgs. 10.17 may even refer to a newly-defined ‘mina of the land’, i.e., an official standard announced at the palace.

Our earliest reference to a standardised mina in Scripture are various references to ‘the shekel of the sanctuary’ in the Mosaic law (Exod. 30, 38, Lev. 5, etc.), discussed in @lettlander’s thread below:

https://twitter.com/lettlander/status/1299353158389567497

But the events of 1 Kgs. 10 belong to a different context and timeframe.

A monarchy has just been established,

and we’ve recently been introduced to the notion of ‘a weight standardised by the king’ (cp. אבן המלך in 2 Sam. 14.26).

A monarchy has just been established,

and we’ve recently been introduced to the notion of ‘a weight standardised by the king’ (cp. אבן המלך in 2 Sam. 14.26).

Perhaps, then, the text of 1 Kgs. 10.17 refers to a similar standardised mina, such as ‘the mina of the land’,

which is known to have defined not a standard mina, but a heavy mina (Fales 1996:16).

which is known to have defined not a standard mina, but a heavy mina (Fales 1996:16).

Cp. also CAD «kakkaru», where a 6,000-shekel talent is identified at Alalakh. If the CAD is right, the talent in question would be a ‘heavy talent’, i.e., a talent of ‘heavy (100-shekel) minas’.

The text of 1 Kgs. 10 therefore gives us an additional reason to think Israel’s mina was composed of 50 shekels.

——————————————

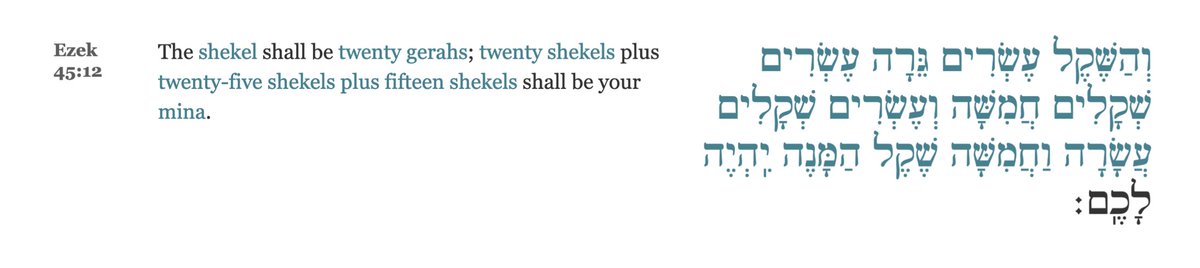

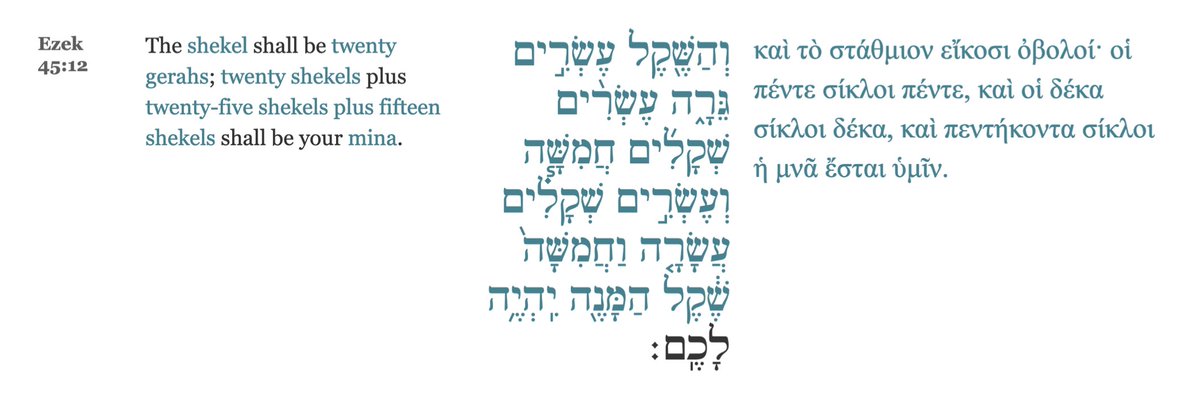

EZEKIEL

Despite the facts set out above, many reference works claim Israel’s mina was composed of *60* shekels.

The main reason why is the text of Ezek. 45.12, which describes what looks to be a 60-shekel mina.

EZEKIEL

Despite the facts set out above, many reference works claim Israel’s mina was composed of *60* shekels.

The main reason why is the text of Ezek. 45.12, which describes what looks to be a 60-shekel mina.

Read in context, however, the text of Ezekiel 45 doesn’t strike me as a good reason to think Israel’s standard mina was made up of 60 shekels;

on the contrary, it strikes me as the exception which proves the rule.

on the contrary, it strikes me as the exception which proves the rule.

As he writes, Ezekiel is in Babylon—a land with a sexagesimal number system.

There, Ezekiel is shown a vision of a new temple governed by new laws.

He is given a six-cubit reed with which to measure the temple and its complex (40.5).

There, Ezekiel is shown a vision of a new temple governed by new laws.

He is given a six-cubit reed with which to measure the temple and its complex (40.5).

He is shown a six-cubit wall and six six-chamber gates,

the chambers of which measure six cubits by six cubits (40.10ff., 41.1, 41.5ff.).

the chambers of which measure six cubits by six cubits (40.10ff., 41.1, 41.5ff.).

He is told about a sacrificial system in which dry measures are a sixth of ephah (45.13) in contrast to the tenth of an ephah prescribed by Mosaic law (e.g., Exod. 29.40, Lev. 5.11, 6.20, etc.),

and in which liquid measures are a third of a hin (46.14 w. 4.11) rather than the quarters and halves standardly prescribed by Mosaic law (Exod. 29.40, Num. 15, 28, etc.).

And, in like manner, he is prescribed a new sexagesimal mina, made up of 60 rather than 50 shekels,

And, in like manner, he is prescribed a new sexagesimal mina, made up of 60 rather than 50 shekels,

which reads as one might *expect* in Greek translations (cp. πεντήκοντα σίκλοι ἡ μνᾶ ἔσται ὑμῖν = ‘fifty shekels will be your mina’) rather than as the Hebrew text states:

——————————————

——————————————

TALENTS

References to the talent in the Biblical narrative are at first very infrequent, but become more frequent over time.

We find an isolated reference to the talent in Exod. 38, where Israel’s plunder from Egypt is weighed up.

References to the talent in the Biblical narrative are at first very infrequent, but become more frequent over time.

We find an isolated reference to the talent in Exod. 38, where Israel’s plunder from Egypt is weighed up.

Thereafter, we don’t find any references to the talent until we reach later stages of the Biblical narrative,

where the talent is referred to initially as a weight (e.g., 1 Chr. 19, 1 Kgs. 9, etc.),

where the talent is referred to initially as a weight (e.g., 1 Chr. 19, 1 Kgs. 9, etc.),

later as a form of currency (though still infrequently) (e.g., 1 Kgs. 16, 2 Kgs. 5, 2 Chr. 25),

and, from the 7th cent. onwards, in much greater frequency (2 Kgs. 15, 18, 23, Dan. 5.25, Ezra 2, 7, 8 w. Matt. 25) (cp. also בלו in Ezra 4.13?).

and, from the 7th cent. onwards, in much greater frequency (2 Kgs. 15, 18, 23, Dan. 5.25, Ezra 2, 7, 8 w. Matt. 25) (cp. also בלו in Ezra 4.13?).

As such, the Biblical narrative displays the sort of pattern we would expect.

(The analysis of these data-points by their assumed Source seems to have caused the aforementioned pattern to be overlooked: e.g., in Kletter 1998:99ff.)

(The analysis of these data-points by their assumed Source seems to have caused the aforementioned pattern to be overlooked: e.g., in Kletter 1998:99ff.)

At Alalakh VII (late 3rd mill.), we have not yet found any references to talents—or at least we hadn’t in 1979 (Zaccagnini 1979). (Even if we have since then, the point remains: references are few and far between.)

And, at Ugarit and Alalakh IV, in the latter half of the 2nd mill., we find occasional references to talents (cp. above w. Zaccagnini 1978),

as we also do in the Amarna tablets (Naaman 1999).

as we also do in the Amarna tablets (Naaman 1999).

Only later, in the 1st mill., in and around Mesopotamia, do heavier weights start to appear in our records in greater frequency (cp. Zaccagnini 2019 w. Kletter 2009:837).

——————————————

——————————————

THE MAKE-UP OF A TALENT

If Israel’s mina was composed of 50 shekels, then Israel’s talent must have been composed of 60 minas (in order to yield the 3,000-shekel talent presupposed by the text of Exod. 38).

If Israel’s mina was composed of 50 shekels, then Israel’s talent must have been composed of 60 minas (in order to yield the 3,000-shekel talent presupposed by the text of Exod. 38).

The Biblical narrative is consistent with such a notion.

Just as its references to shekels identify fifty as a ‘round number’ of shekels, so its references to talents identify sixty as a ‘round number’ of talents.

Just as its references to shekels identify fifty as a ‘round number’ of shekels, so its references to talents identify sixty as a ‘round number’ of talents.

In broad terms, references to payments of talents (‘kikkar’) in the Biblical narrative consist of:

a] a few early references to small numbers of talents (10 or less),

b] some later references to large numbers of talents (1,000 or more), and

a] a few early references to small numbers of talents (10 or less),

b] some later references to large numbers of talents (1,000 or more), and

As can be seen, whereas the Bible’s references to shekels (considered earlier) were more consistent with a decimal than a sexagesimal system, vice-versa is true of its references to talents.

While only 50% of the weights above are divisible by 50, 70% of them are divisible by 60 (or 30),

and the number 666 sounds decidedly sexagesimal (for obvious reasons).

——————————————

and the number 666 sounds decidedly sexagesimal (for obvious reasons).

——————————————

ISRAEL IN ITS WIDER CONTEXT

Whereas Mesopotamia’s weights and measures are fundamentally sexagesimal, Israel’s strike me as more *decimal-friendly*.

As we’ve noted, Israel’s mina was composed of 50 shekels, and Israel’s shekel was composed of 20 gerahs.

Whereas Mesopotamia’s weights and measures are fundamentally sexagesimal, Israel’s strike me as more *decimal-friendly*.

As we’ve noted, Israel’s mina was composed of 50 shekels, and Israel’s shekel was composed of 20 gerahs.

As such, Israel’s mina was composed of 1,000 parts.

Israel’s non-monetary weights also seem to reflect a preference for base 10.

Israel’s largest attested dry measure—viz. the ‘homer’ (חֹמֶר)—was apparently composed of 10 ‘ephahs’ (איפה) (cp. Ezek. 45.11, 14),

Israel’s non-monetary weights also seem to reflect a preference for base 10.

Israel’s largest attested dry measure—viz. the ‘homer’ (חֹמֶר)—was apparently composed of 10 ‘ephahs’ (איפה) (cp. Ezek. 45.11, 14),

and Israel’s ephah was composed of ten ‘omers’ (עֹמֶר) (per Exod. 16.36).

As such, Israel’s primary dry measure was composed of 100 parts,

which, as we’ve noted, made Israel’s metrological system very different from Mesopotamia’s.

As such, Israel’s primary dry measure was composed of 100 parts,

which, as we’ve noted, made Israel’s metrological system very different from Mesopotamia’s.

Egypt, however, is well known for—and perhaps even distinctive in—its decimal orientation.

Below are Egypt’s equivalents of the shekel, mina, and talent, which are related in the ratio 100:10:1.

Below are Egypt’s equivalents of the shekel, mina, and talent, which are related in the ratio 100:10:1.

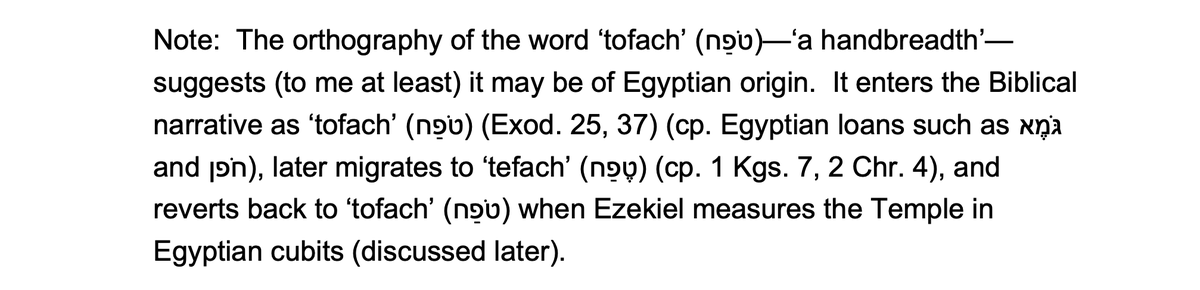

Other Egyptian influences are evident in Israel’s weights and measures.

For a start, a number of Israel’s weights and measures are thought to be Egyptian loanwords.

For a start, a number of Israel’s weights and measures are thought to be Egyptian loanwords.

One example is the (ten-based) ‘ephah’, which is thought to derive from the Egyptian «ypt».

Another is the ‘span’ (זֶרֶת = ‘zeret’), thought to derive from Egyptian «ḏrt».

Another is the ‘span’ (זֶרֶת = ‘zeret’), thought to derive from Egyptian «ḏrt».

Israel’s measures also seem to reflect known Egyptian conventions.

In ancient Egypt, the cubit was composed of six palms (‘shesep’)—or, in the case of the long cubit, seven palms—,

and the palm was composed of four fingerbreadths (‘djeba’).

In ancient Egypt, the cubit was composed of six palms (‘shesep’)—or, in the case of the long cubit, seven palms—,

and the palm was composed of four fingerbreadths (‘djeba’).

As such, the Egyptian cubit was composed of 24 finger-widths—or, in the case of the long cubit, 28 finger-widths (Scott 1959:24, Williams 2020:1.7).

Israel’s system seems remarkably similar.

In Israel, the cubit was composed of three handspans (‘zeret’),

Israel’s system seems remarkably similar.

In Israel, the cubit was composed of three handspans (‘zeret’),

each of which was composed of two palms (‘tofach’),

each of which was in turn composed of four finger-breadths (Bashan 2006:707).

Consequently, both the Egyptian and the Hebrew cubit were composed of 24 finger-breadths.

each of which was in turn composed of four finger-breadths (Bashan 2006:707).

Consequently, both the Egyptian and the Hebrew cubit were composed of 24 finger-breadths.

And, as we’ll now see, both of them appear to have come in two varieties: a standard variety (24 finger-breadths in length) and a longer variety (28 finger-breadths).

In 2 Chr. 3, the Chronicler records the measurements of Solomon’s temple in ‘old cubits’ (2 Chr. 3.3). And, in Ezek. 40, Ezekiel measures his eschatological temple with a reed ‘a cubit plus a palm’ in length.

Since these two passages alone in the Biblical narrative (both of which record the dimensions of a temple) tell us which cubit they use, it doesn’t seem too much of a stretch to think we’re supposed to associate them in some way.

I therefore take the old cubit of 2 Chr. 3 to be identical with the ‘cubit plus a handbreadth’ of Ezek. 40,

which makes Israel’s old cubit a sixth longer than Israel’s standard cubit (since a cubit of 6 palms plus an extra palm makes 7 palms).

which makes Israel’s old cubit a sixth longer than Israel’s standard cubit (since a cubit of 6 palms plus an extra palm makes 7 palms).

If I’m right, Israel’s standard cubit would have corresponded to Egypt’s standard cubit, and Israel’s old cubit would have corresponded to Egypt’s long cubit,

though neither would have corresponded to Mesopotamia’s cubit(s) (of 27 or 30 fingerbreadths: Kletter 2009:840, Stone 2014:3, 5).

In sum, then, Israel’s weights and measures reflect a distinctly Egyptian influence.

In sum, then, Israel’s weights and measures reflect a distinctly Egyptian influence.

At first blush, that may seem a strange notion.

After all, Israel’s *calendar* doesn’t reflect an Egyptian influence;

it is entirely Mesopotamian/Canaanite.

After all, Israel’s *calendar* doesn’t reflect an Egyptian influence;

it is entirely Mesopotamian/Canaanite.

Given the tenor of the Mosaic law, however, we should not be surprised by the disconnect between Israel’s weights and measures and Israel’s calendar.

When the Israelites left Egypt, YHWH assigned them a completely new calendar, complete with details of how and when its feasts were to be observed.

YHWH did not, however, give the Israelites a new set of weights or measures;

YHWH did not, however, give the Israelites a new set of weights or measures;

rather, he explained the requirements of the law and sacrificial system to them in terms they already knew and understood.

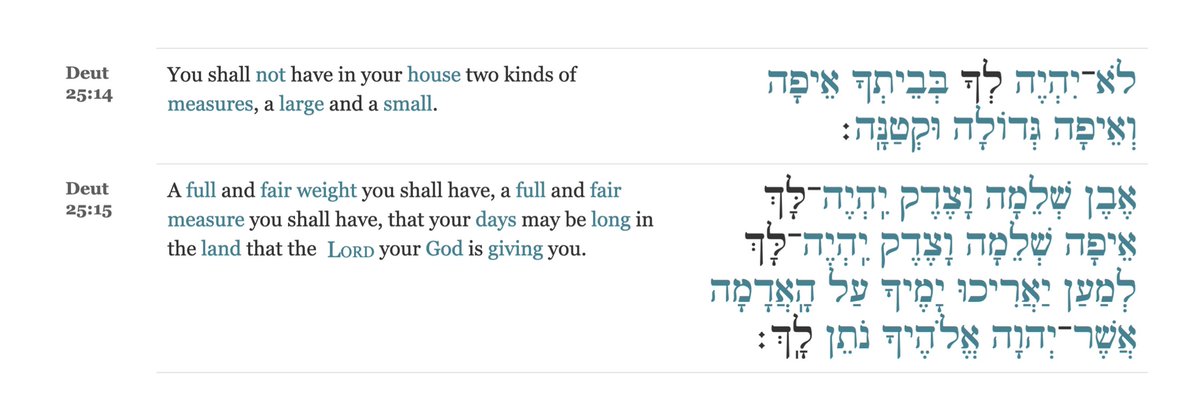

His concern was not *which* weights and measures they used; it was one of consistency.

His concern was not *which* weights and measures they used; it was one of consistency.

Whichever weights and measures the Israelites used, they were to same measures when they bought as when they sold,

which seems an apt note on which to end.

</THREAD>

——————————————

which seems an apt note on which to end.

</THREAD>

——————————————

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh