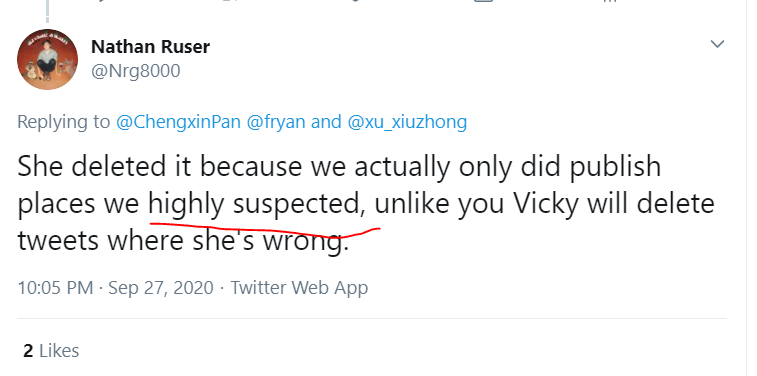

Engage in your research in good faith I did. It's by your (ASPI) own admission that your research is based on 'highly suspected', 'possible camps', 'could be', waiting-for-coroboration-type speculation and insinuation. There is nothing good faith about this type of practice

https://twitter.com/xu_xiuzhong/status/1310194215809249284

and it's everything against the spirit of research. Also research in good faith, in this case, China's policy in Xinjiang, should be to engage with the policy and its pros and cons. Like China's one-child policy, or any Chinese policy, it should be scrutinised and criticised.

But such criticisms should be based on solid evidence and bona fide intentions to help improve its policy, or help it changed. And research in good faith should also invite or at least welcome others to scrutinise one's own research, rather than trying to silence and intimidate

them, using all sorts of techniques and name-calling. Again there is nothing good faith about those kinds of behaviours. Research in good faith also entails comparing China's policy to similar policies in other countries: if these are concentration camps, then do please compare

them to typical concentration camps in Nazi Germany, US 'reserves' for Native Indians, US WWII internment camps, Australia's stolen generation and institutionalised abuses of aboriginal people, US Abu Ghraib prison, US Guantanamo Bay detention camps, Australia's onshore and off

detention centres, and so on. Such research can point out how China's policy can learn from Western practices, what to avoid, what is new in China's policy that is more deplorable and horrendous, compare their long-term harming effects on the respective victims, etc. If ASPI has

done such research, I'd be very interested to read. If not comparative studies, then single case studies on those other concentration camps are also valuable. If you haven't done any of such research, please explain why not. Also, if China's policy amounts to genocide, then it's

only appropriate to compare it to other known genocides, starting perhaps from the genocides of Native Indians, Australian Aboriginals, the Armenian genocide, genocides in Cambodia and Rwanda, etc. If China's genocide is not comparable, then redefine genocide, explain what's

changed, what's the difference, and so on. This is not whataboutism or false equivalence. In most cases, I do agree that there is perhaps no equivalence. But then research in good faith is needed to establish why there is no equivalence, what is worse in China's Xinjiang case etc

Simply evoking such terms as 'concentration camps' and 'genocide' (given their historical precedents and legal & moral connotations) without definition or comparative analysis is anything but in good faith in my view. Reducing those terms to emotive appeal and virtue signalling

trivialise the seriousness of such matters and sufferings of real victims of those atrocious acts and policies. Over time, it also diminishes the impact of those terms and makes them susceptible to political sloganeering. Such wouldn't help any real victims of concentration camps

or genocides. It may well serve, willingly or unwittingly, to distract real atrocities going on elsewhere. Research in good faith also calls for contextualising the issues in question, eg, how China's policy emerged, what factors caused it, whether China's anti-terrorism policy

is wrong or unjustified, whether US State Dept is wrong to designate ETIM as a terrorist organization, what policy China should do to counter terrorism and de-radicalise terrorists. What can China learn from UK's Desistance and Disengagement Programme (DPP), the US's Community

Corrections, and France's Deradicalisation Programs, etc.? What's worked, what hasn't? What's the difference between China's anti-terrorism policy and those of other countries? Ultimately, research in good faith, for an 'independent, non-partisan think tank' like yours, should

also document systematic destruction, war crimes and human rights violations in places like Iraq, Afghanstan, Libya, etc. and launch a Middle East Data Project. If there is such a project done by ASPI, I'd like to know. If not, why not? In my view,

https://twitter.com/1maria_ml/status/1255545063347826689

such a project would be equally, if not more, relevant to Australia's strategic policy and your mission to 'broaden public knowledge about the critical strategic choices our country will face over the coming years'. After all, Australia has been one of the major participants in

the US-led wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and the broader Middle East. Those wars have cost Australian tax-payers billions of dollars, and dozens of lives. More importantly, those wars cost more than a million of others' lives, and created millions of refugees and many terrorists.

Dead Iraqis can be unseen, unheard & forgotten, but what about their relatives & loved ones? Any plan to document their fate, where they are, what they think? Some of those refugees have come to our shores, and some home-grown terrorists have been radicalised as a result. Aren't

these issues central to Australia's strategic policy and its national interests? This doesn't mean APSI, if true to its name, should only focus on those questions. By all means devote most of your resources to data project on China, but it's beyond belief that for researchers

like you, who are in good faith, to be so blind to those research questions. If we don't reflect on what went wrong with the US-led Australia-followed invasions in the Middle East, who is to say that we won't make similar mistakes again? Also, if you're committed to research in

good faith and to being an independent and non-partisan think tank, I wonder if you'd accept money and funding from Chinese arms manufacturers, do projects for Chinese Foreign Ministry, Department of Defense, and so on. If not, then why not? Is it because Chinese arms

manufacturers contributed to China's assertiveness in the South China Sea, and complicit in Xinjiang, but unlike your sponsers such as Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Raytheon, haven't supplied weapons to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan? Or is it because China's DoD

wasn't part of the coalition of the willing in the Middle East? Or simply because China is an authoritarian state unlike us? .... All these are genuine questions sparked by your reference to research in good faith, and I'd like to hear your thought.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh