What will be the long-term consequences of the pandemic?

Few, if any, answers are clear. But history might provide us with some clues 🔎 trib.al/1aHZCyP

Few, if any, answers are clear. But history might provide us with some clues 🔎 trib.al/1aHZCyP

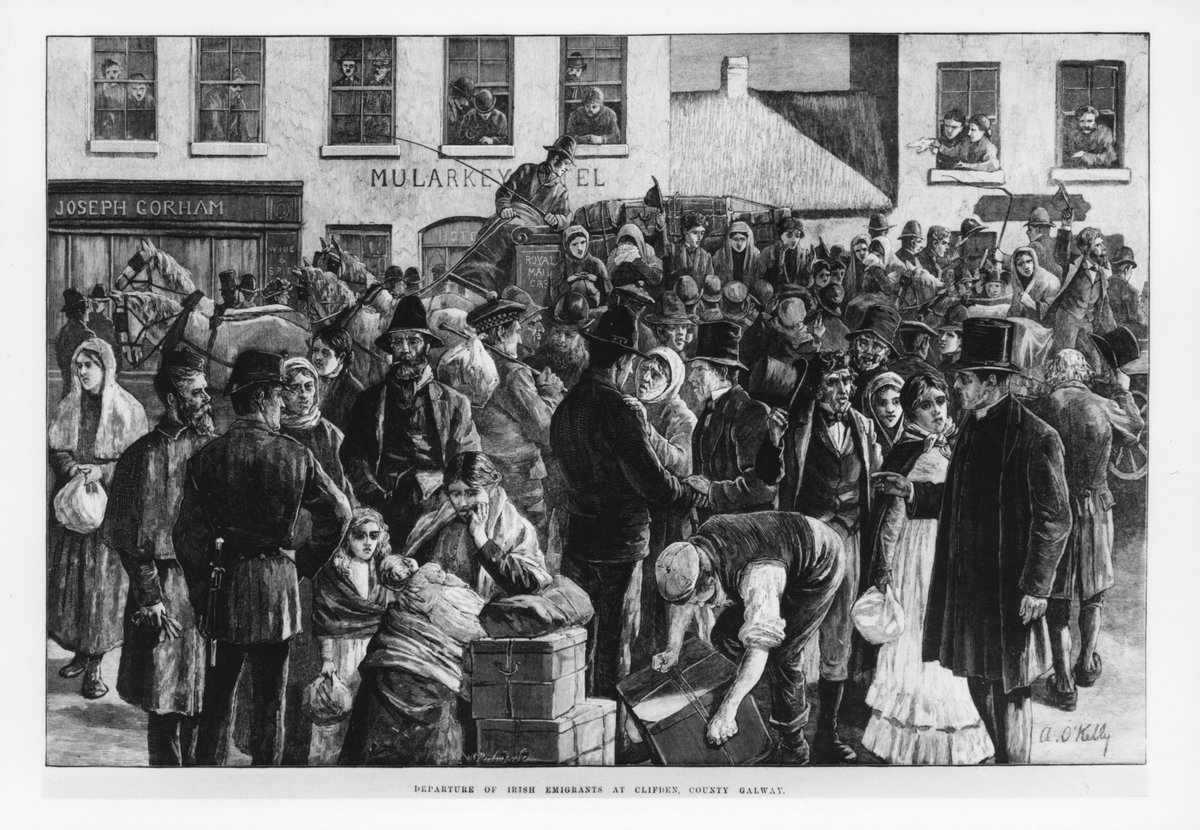

🥔Let’s start 175 years ago with the Irish Potato Famine, which led to appalling suffering and changed the course of history trib.al/1aHZCyP

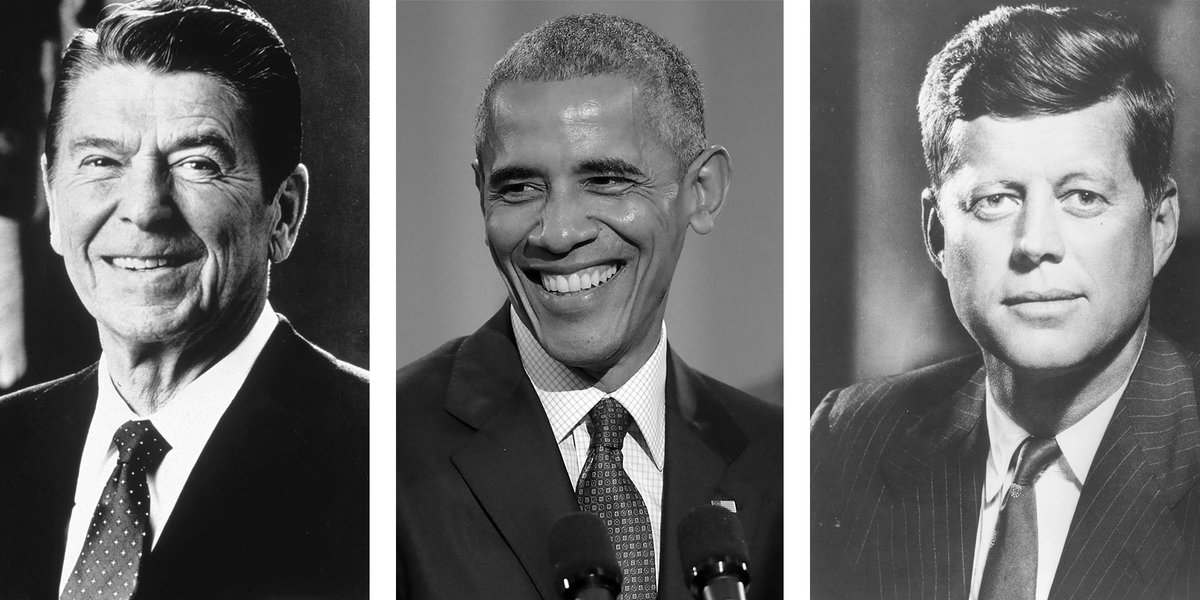

Without the potato blight, it’s unlikely the U.S. would have benefited from the influx of Irish immigrants. Three presidents to date have descended from migrants who fled the famine:

🇺🇸Kennedy

🇺🇸Reagan

🇺🇸Obama

Joe Biden would be the fourth trib.al/1aHZCyP

🇺🇸Kennedy

🇺🇸Reagan

🇺🇸Obama

Joe Biden would be the fourth trib.al/1aHZCyP

The impact of the emigration can still be felt in Ireland’s population:

🗓️2019: 4.9 million people, the most in over a century

🗓️1850: 5.1 million people

Over the same period, the population of England and Wales rose to 59.4 million from 17.9 million trib.al/1aHZCyP

🗓️2019: 4.9 million people, the most in over a century

🗓️1850: 5.1 million people

Over the same period, the population of England and Wales rose to 59.4 million from 17.9 million trib.al/1aHZCyP

How did the famine happen?

@EconCharlesRead argues the British response was undermined by financial mismanagement that led to a crisis startlingly similar in its fundamentals to those of our time trib.al/1aHZCyP

@EconCharlesRead argues the British response was undermined by financial mismanagement that led to a crisis startlingly similar in its fundamentals to those of our time trib.al/1aHZCyP

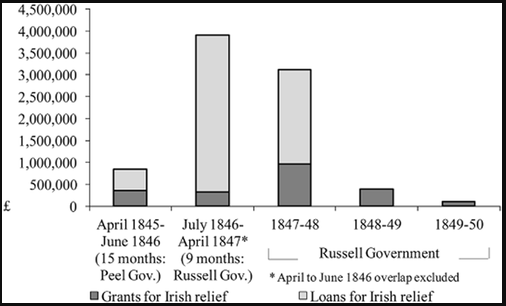

After Robert Peel gave way to Lord Russell as prime minister, Irish taxes were hiked, and grants became loans that would need to be repaid.

Why the U-turn? Blame the bond market, writes @johnauthers trib.al/1aHZCyP

Why the U-turn? Blame the bond market, writes @johnauthers trib.al/1aHZCyP

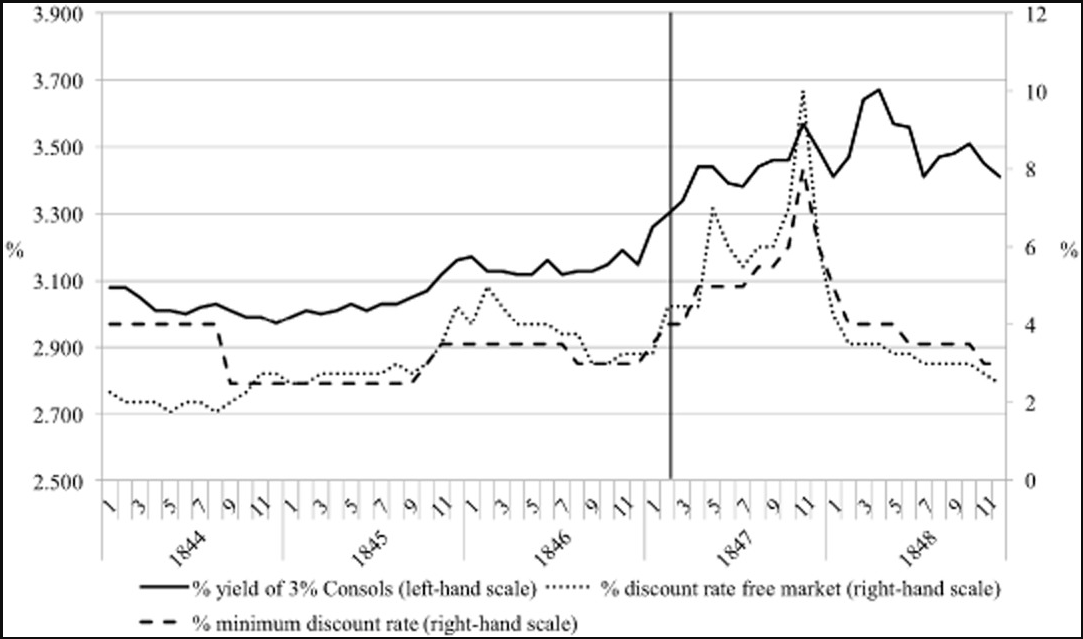

This is what happened to the interest rates on consols, which dominated Treasury lending at the time, after the government attempted to borrow more money to deal with the famine.

The bond market was in revolt. So was the gold market trib.al/1aHZCyP

The bond market was in revolt. So was the gold market trib.al/1aHZCyP

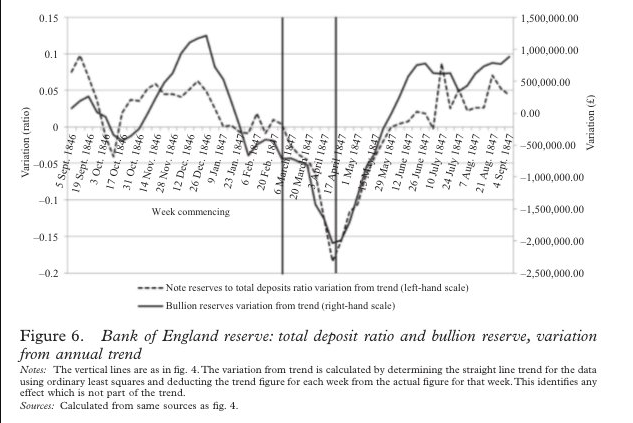

As British politicians tried to raise money to fund the Irish relief effort, investors decided they wanted their money in gold, not paper.

So they placed the burden onto the Irish themselves by hiking taxes. The result was famine, death and emigration trib.al/1aHZCyP

So they placed the burden onto the Irish themselves by hiking taxes. The result was famine, death and emigration trib.al/1aHZCyP

Fast forward to 1918 and the Spanish flu.

The after-effects of this pandemic suggest that the financial impact can be counterintuitive trib.al/1aHZCyP

The after-effects of this pandemic suggest that the financial impact can be counterintuitive trib.al/1aHZCyP

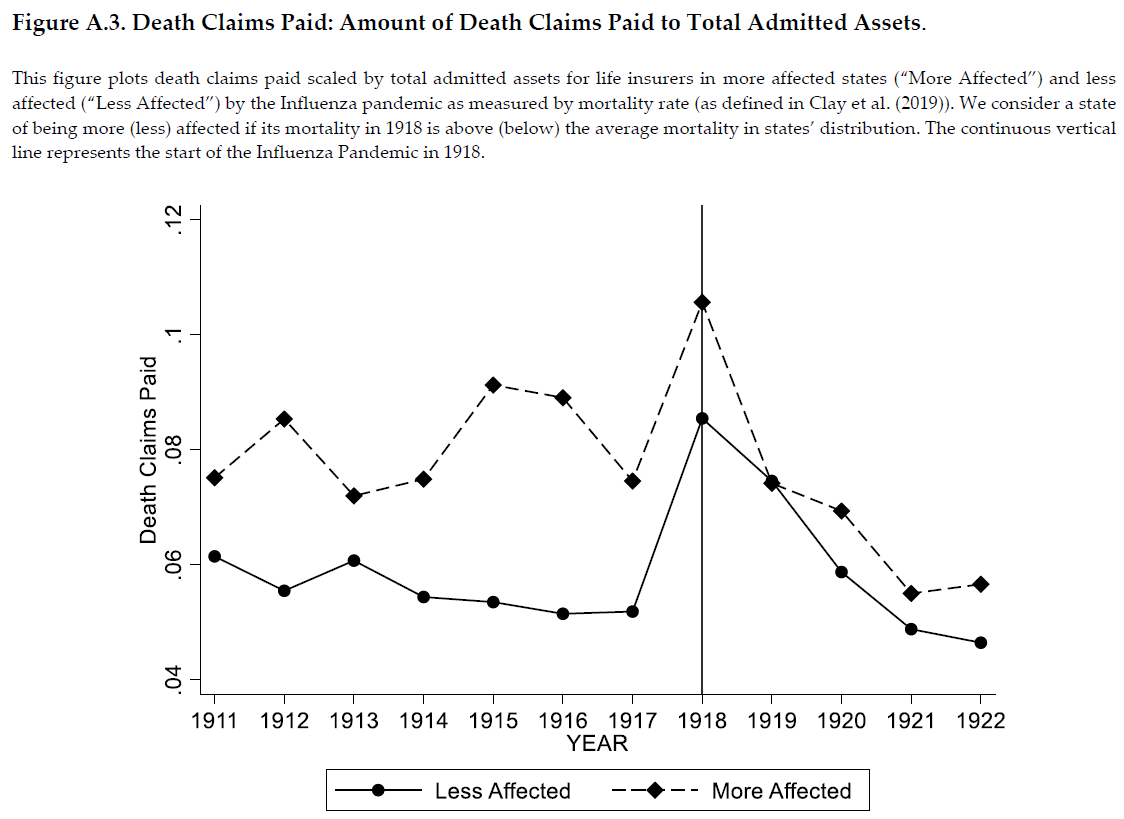

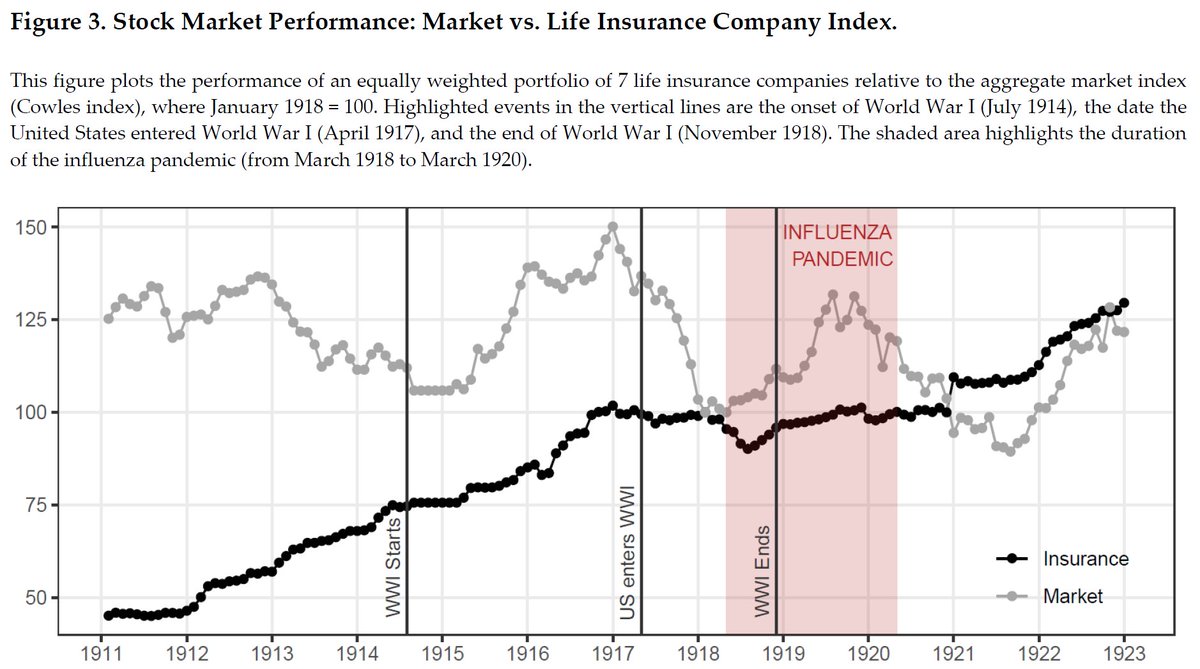

You might think that an epochal pandemic would inflict terrible damage on the life insurance industry. But it didn’t.

In fact, a new research paper suggests the flu was a “blessing in disguise” for American life insurers

In fact, a new research paper suggests the flu was a “blessing in disguise” for American life insurers

https://twitter.com/GertjanV_/status/1309098527809773572?s=20

Death claims initially rose sharply in the first year of the pandemic.

But importantly, they then fell sharply to lower rates than in much of the preceding decade, while the pandemic led to a rush to buy life insurance in 1919 trib.al/1aHZCyP

But importantly, they then fell sharply to lower rates than in much of the preceding decade, while the pandemic led to a rush to buy life insurance in 1919 trib.al/1aHZCyP

This led to a boon:

📈Life insurers’ shares made up their lost ground within months of the pandemic’s end

💰Companies were able to raise far more money in equities

💸Incorporations of life companies surged in 1919, making it easier to absorb the impact trib.al/1aHZCyP

📈Life insurers’ shares made up their lost ground within months of the pandemic’s end

💰Companies were able to raise far more money in equities

💸Incorporations of life companies surged in 1919, making it easier to absorb the impact trib.al/1aHZCyP

Financial mechanisms turned the potato blight into a humanitarian catastrophe. After the Spanish flu, financial markets helped minimize the damage.

Bear this disparity in mind when trying to predict how markets will deal with the aftermath of 2020 trib.al/1aHZCyP

Bear this disparity in mind when trying to predict how markets will deal with the aftermath of 2020 trib.al/1aHZCyP

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh