1. Weekend Reading. With the USDA Oct Crop Production report coming up next week, thought it would be a good time to revisit this 2013 article: "Do Big Crops Get Bigger and Small Crops Get Smaller? Further Evidence on Smoothing in U.S. Department of Agriculture Forecasts"

2. The article was published in 2013 in the Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics (the southern ag econ journal for you old timers out there). Free access here: ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/143639/

3. First want to say what a great experience it has been over the years publishing in the JAAE . I appreciate all the work the editors have done over the years. And Olga, one of my co-authors on the 2013 paper, is one of the new co-editors!

4. Now back to the paper. We already knew from earlier research that USDA corn and soybean crop production forecast revisions were positively correlated across report months. What we wanted to test was the old market saw that "Big crops get bigger and small crops get bigger"

5. In other words, when you have great weather USDA corn and soybean crop production estimates will tend to grow moving from August through the January forecasting cycle. This belief seems deeply embedded in the marketplace.

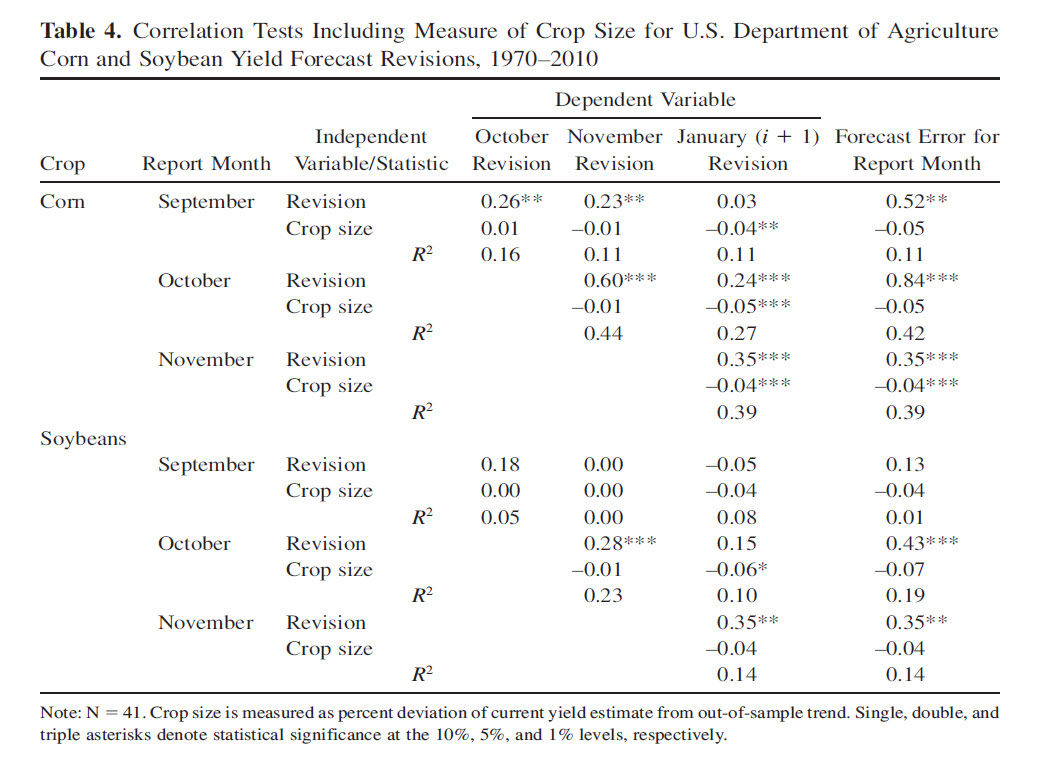

6. This table has the key results. Shows results of regressions of production forecast revisions on future revisions and a measure of crop size. Not much there on crop size. So, why do so many people believe the old marketing saying?

7. My view is that this is a case of hindsight bias. People pick out past years where USDA forecasts have risen from Aug to Jan and we had big crops. So there you go. Case closed, right? Wrong.

8. The problem occurs when you ask can you do this looking forward in real-time? The problem is knowing when you are in a big/small crop year or not. This is not nearly as easy to figure out as you may think.

9. But even though the old marketing saying is not literally true, this does not mean there is no smoothing in USDA corn and soybean production forecasts in real-time. It's definitely there.

10. Go back to Table 4. Look at the last column. Correlation of current month forecast revision with forecast error for that month. Same thing as correlating current month revision with sum of all future remaining revisions.

11. Pretty eye-popping results. Take September for corn. Sep corn forecast revision has a 0.52 correlation with the net revision between Oct and Jan. That is really high. Even higher at 0.84 in Oct. Not as high and consistent in soybeans but tendency still there.

12. Bottom-line. Big crops don't get bigger and small crops don't get smaller, but who cares. Regardless of crop size pretty high degree of smoothing in USDA corn and soybean production forecasts over time. We can use that!

13. Of course have to add the caveat that data for this study is 10 years out of date. But I think you get the same thing if you update the analysis.

14. Last but not least, note that Sep revisions for USDA corn and soybean production forecasts were negative. History says that there are high odds that by the time we get to Jan that the forecasts will be even lower.

@threadreader unroll

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh