Today in pulp... what exactly IS pulp? What does this word mean and is it important?

Let's try and find out... #SaturdayThoughts

Let's try and find out... #SaturdayThoughts

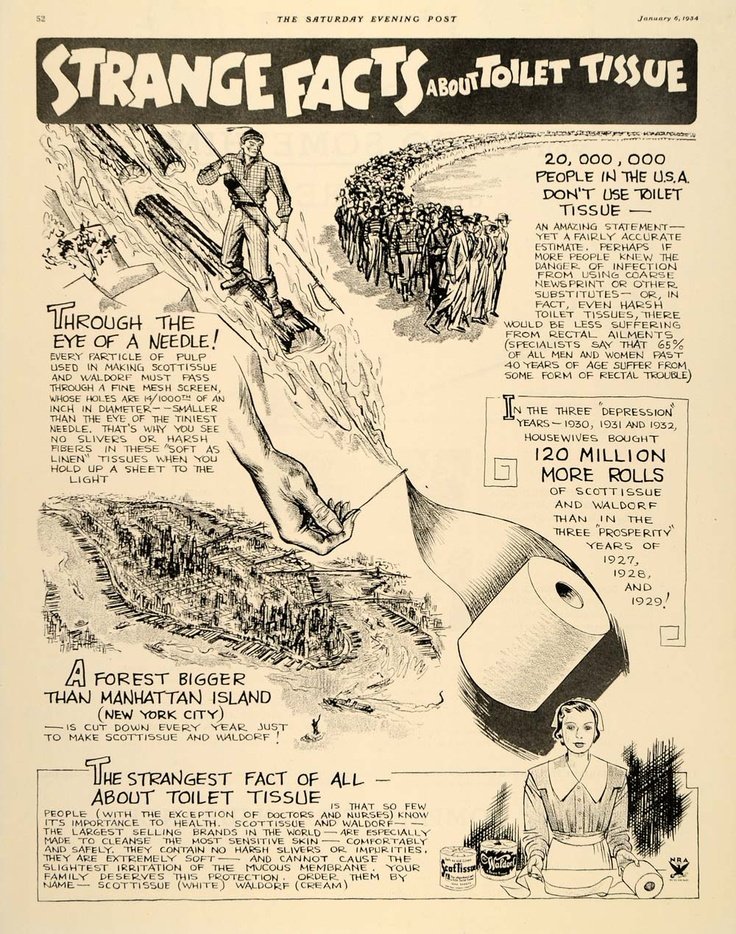

'Pulp' is a term for a type of basic paper stock, made from wood chips or plant fibres. By the 1890s mass production, improved distribution methods and advances in printing combined to make it a viable stock for cheap magazines, amongst other things.

And in the 1890s cheap story magazines, printed on pulp paper, began to appear. Low prices and widespread distribution meant pulp magazines could be a viable business, even if margins were tight.

The timing was auspicious: monthly story magazines had been around for many decades, along with the lurid 'penny dreadfuls' and 'dime novels.' Literacy rates were increasing in the US and Europe. Advertising had become an important income stream for publishers to tap into...

But there's something missing in the traditional story of pulp's birth: something more than technology and distribution...

Marketing!

Marketing!

Marketing is different from sales: it focuses on identifying, segmenting, understanding and exploiting a target market. It's goal may be market share, market dominance or customer loyalty - but its methods are strategic and rigorous.

Marketing emerged in the 1910s as a branch of economics: what other factors, apart from price, scarcity and labour costs, were responsible for economic growth? The ideas of marketing defined the 20th century, and the pulps were one of the first industries to seized on them!

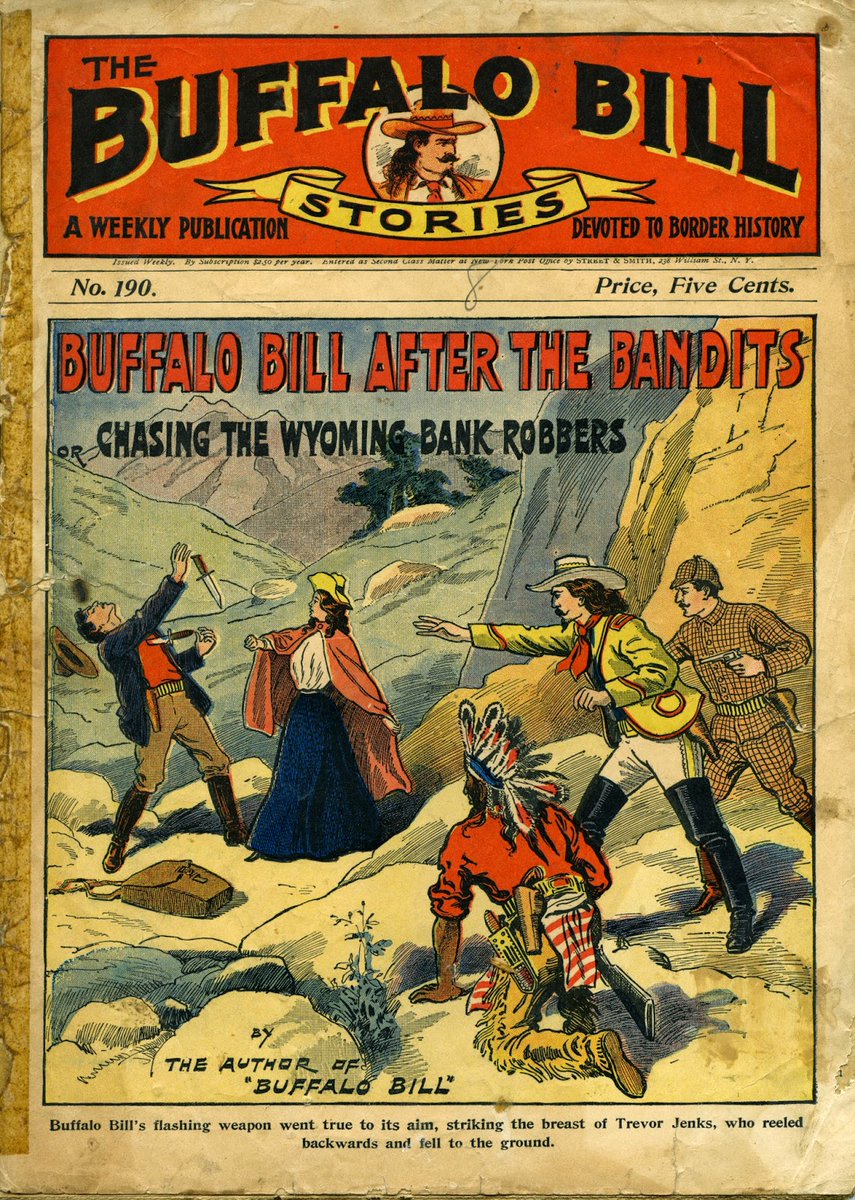

For an example let's look at Black Mask Magazine, launched by journalist H. L. Mencken and theatre critic George Jean Nathen in 1920 as a way to subsidize their slick, influential, but loss-making magazine The Smart Set.

Initially Black Mask published a traditional mix of adventure, mystery, romance and detective stories. After eight issues, and with their money made, Mencken and Nathan sold the pulp title to its publishers and went back to the world of slicks.

And it was editor Philip Cody who used the techniques of marketing to turn Black Mask into a huge success. He built a strong relationship with the readers, asking them for ideas and feedback to help him shape the magazine to better match their tastes.

He also used specific writers - Raymond Chandler, Erle Stanley Gardner - who could nail the kind if story his readers said they wanted: gritty, hard-hitting and pacey.

Cody, later followed by J.T. Shaw, were doing something rather special. They weren't just selling a product - a story magazine. They were offering a service: the service of an expert editor, carefully curating content for a specific and well understood audience segment.

Hugo Gernsback took the same approach with science fiction. Amazing Stories wasn't just a story compendium, he carefully nurtured a relationship with is audience through editorials and market research. Gernsback, as much as the magazine, was the commodity you were buying into.

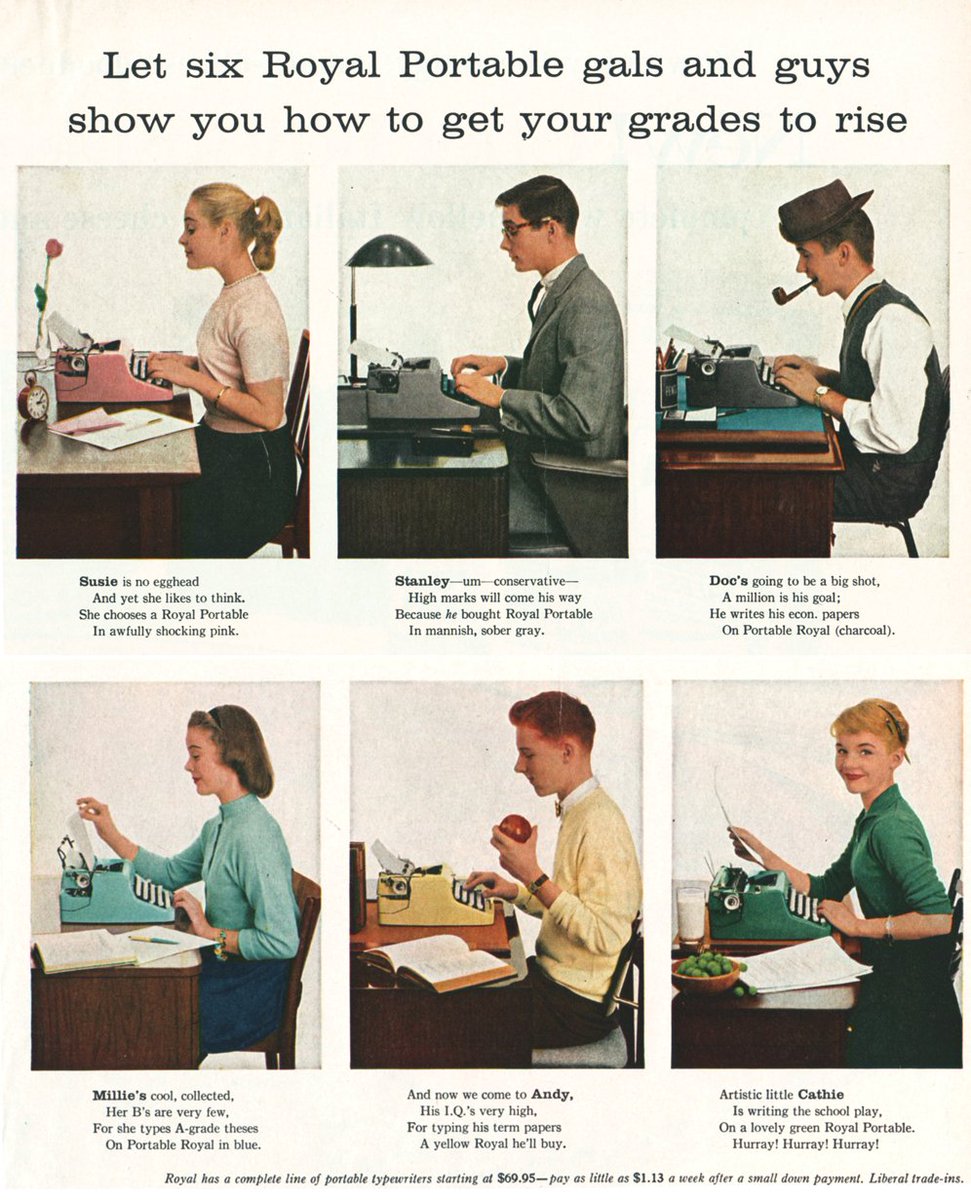

This hyper-targeted, marketing-driven approach became the hallmark of successful pulp. It also proved alluring to advertisers. Detailed customer segmentation data was available to help maximize their effectiveness.

You see from a publisher's point of view pulp isn't a writing style, a genre, or a commodity: it's a strategic approach to developing long-term value from an audience through careful application of modern marketing techniques.

Pulp is honed to your tastes - both actual and latent. It's a more personalized approach to publishing, built on the ability of the publishing house to understand you and serve you what you like. This stuff hits the spot - that's the true hallmark of pulp.

Stan Lee, Gary Gygax, George Lucas, Mark Zuckerberg: they've all in their own way used the techniques of strategic marketing to build up incredible empires of content creation and provision based on this insight. And it all started in the pulps!

More tales another time...

More tales another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh