#TheCompleteBeethoven #443

Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op. 93 (1812)

1/ The first surprise about a symphony full of surprises is that it wasn't supposed to be a symphony at all.

Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op. 93 (1812)

1/ The first surprise about a symphony full of surprises is that it wasn't supposed to be a symphony at all.

2/ Beethoven at first intended it to be a piano concerto. The first draft contains the opening theme and music that's clearly related to later themes too, but it ends in a cadenza for solo piano, and passages in the sketches that follow are marked "solo" and "tutti".

3/ He started the piece straight after No. 7. Following a new symphony with a new piano concerto would once have been no surprise at all. He played Concerto No. 4 between the premieres of Symphonies 6 & 5, and No. 3 was composed to go with a symphony too.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1259404297051279361?s=20

4/ But a new piano concerto with Beethoven himself as soloist would have been surprising indeed in 1812. His worsening deafness prevented him performing his last concerto. He sketched other concerto ideas as late as 1815, but eventually abandoned them all.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1305401105799671810?s=20

5/ Another surprise is how he could compose such relentlessly joyful music when his personal life was so distressing. He began it as he wrote a letter to his "Immortal Beloved", a letter he probably never sent. It seems that this affair ended in heartbreak like all the others.

6/ Beethoven did not name his 'Immortal Beloved', but many believe the letter's intended recipient was Antonie Brentano, his close friend since 1810. The Brentanos left Vienna in late 1812 as he finished the symphony. Antonie and Beethoven never saw each other again.

7/ Yet we shouldn't be surprised that Beethoven the artist could transcend the trials that Beethoven the man had to suffer. A decade before, in another unsent letter, he had considered suicide as he was finishing his joyous and sunny Second Symphony.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1256108752945758209?s=20

8/ Beethoven suffered more than a broken heart as he composed the 8th. At Teplitz he at last met his hero Goethe (a meeting set up by Antonie's sister-in-law Bettina, another 'Immortal Beloved' candidate) but "the titans of their time could find no common ground" (Jan Swafford).

9/ A second summer at the spa resort failed to restore him where the first had succeeded. He took to his sickbed on his way home to Vienna and upon his return, but soon had to rouse himself to rush to Linz. It wasn't only his own love life that caused Beethoven pain in 1812.

10/ He finished the Eighth and wrote music for the cathedral at the request of its Kapellmeister, but he wasn't in Linz to work. Ludwig was visiting his brother Johann to try and prevent him from marrying his 'Immoral Beloved', Therese von Obermeyer.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1315727348231274497?s=20

11/ Beethoven was desperate to prevent a repeat of his other brother's scandalous union. He thought Therese, who had an illegitimate child, "a tramp and a gold-digger" (Jan Swafford). When he demanded Johann send her away, the brothers came to blows.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1283280905130450944?s=20

12/ Ludwig obtained a legal order banishing Therese from town as "an immoral woman" (Swafford). Johann married her in retaliation, bringing about the nightmare he'd tried to prevent. The marriage was miserable and there were bitter recriminations between the brothers ever after.

13/ Those seeking links between an artist's life and work will find nothing in the Eighth: no suffering heroically borne, no trauma triumphantly overcome. Surprisingly, Beethoven's symphonies of 1812 start to subvert the very style that made him famous.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1310266751117074433?s=20

14/ The Seventh dispensed with the heroic style of previous middle-period symphonies. There's no heroic narrative or unifying musical motive. At only half the length of the Eroica, Beethoven's 'anti-heroic' Eighth discards the heroic scale as well.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1292366833564233728?s=20

15/ Symphonies 3-7 created the blueprint that future composers would follow. No. 8 appropriates Beethoven's own heritage to create "the most ebulliently experimental symphony in the canon" (Tom Service). The Romantic hero becomes the classical re-animator.

16/ Not since his first had Beethoven written a symphony so similar on the surface to those of his teacher Haydn (anyone who calls No. 4 'Haydnesque' isn't really listening), who died three years before the Eighth.

But appearances can be deceptive ...

But appearances can be deceptive ...

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1241989812875337728?s=20

17/ The master would surely have loved the cheeky games his student plays with his style.

"Classical-period dimensions mask its subtleties and forward-looking features ... surprise and paradox stand out more sharply than in any other Beethoven symphony." - Lewis Lockwood

"Classical-period dimensions mask its subtleties and forward-looking features ... surprise and paradox stand out more sharply than in any other Beethoven symphony." - Lewis Lockwood

18/ There's only one way to reveal all the surprises Beethoven unleashes on his unsuspecting 19th-century listeners. It's analysis time! This video is my reference, and this time I'll try to keep my comments as short and sweet as the symphony itself.

19/ I once studied this at @OpenUniversity. How much do I remember? Let's find out!

The first Beethoven symphony with no introduction at all (even the Pastoral starts by pausing), No. 8 launches straight into the action (0:36).

"It opens with a closing gesture" - Barry Cooper

The first Beethoven symphony with no introduction at all (even the Pastoral starts by pausing), No. 8 launches straight into the action (0:36).

"It opens with a closing gesture" - Barry Cooper

20/ The six-note motif, landing firmly on the tonic, also ends the movement (8:46) but unlike No. 7, where one motif governs every aspect of the music, No. 8's first movement delights in integrating diversity. Its exposition (0:36-2:22) has no fewer than six thematic segments.

21/ 1: The motif generates a three-part theme (0:36-0:47) with a middle section for winds alone. The third part also lands squarely on the tonic (more on that later).

2: A leaping violin theme (0:48) over a tremolo cloud. Its continuation skips surprisingly onto D major (1:11).

2: A leaping violin theme (0:48) over a tremolo cloud. Its continuation skips surprisingly onto D major (1:11).

22/ 3: A one-bar pause like a look of startled surprise (1:09) heralds a lyrical (strings) yet jaunty (bassoon) second subject in the 'wrong' key of D. At 1:21 it realizes where it's 'meant' to be, and slips demurely down to the 'correct' key of C major where winds carry it on.

23/ 4: Another cloud of harmonic uncertainty (1:29) recalls the faltering rhythm (1:01) that heralded the earlier startled surprise. The music crescendos away from confusion.

5: The syncopated pulse of a new leaping figure (1:48) introduces a new lyrical theme presented twice.

5: The syncopated pulse of a new leaping figure (1:48) introduces a new lyrical theme presented twice.

24/ 6: More new hoofsteps (2:09) end in leaping arpeggios and jumping octaves, all emphasizing the firm ground of C we surprisingly missed before.

Beethoven's previous symphony was only half-way through its introduction by the time No. 8's densely-packed exposition ends (2:22).

Beethoven's previous symphony was only half-way through its introduction by the time No. 8's densely-packed exposition ends (2:22).

25/ Those final jumping octaves animate the start of the development (4:09) which, surprisingly (I'll be using that word a lot) throws out the filling from the exposition's sandwich. First they accompany the return of the opening motif, rising through the woodwind (4:13).

26/ 6's arpeggios return on full orchestra and 1. and 6. are juxtaposed twice more in the same manner as the harmony starts to move its feet. Now even 6. is cast aside (4:49), the opening figure repeating more and more forcefully as the music drives dementedly from key to key.

27/ As all music students know, sonata form development sections end with a dominant preparation for the return of the opening material in the home key. Sure enough the bass line reaches C (5:22). Tension builds and builds as we await the expected release of the recapitulation.

28/ But as students of Beethoven know, a hallmark of his style is the dramatization of form. Structural joins become momentous events, none more so than the recapitulations of his symphonies, so prepare yourself for shock and surprise as well as release.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1274658523050315776?s=20

29/ As students of sonata form know, the recapitulation is "a double return" (Lewis Lockwood): a structural return of the opening theme in the home key, and a homecoming that restores stability after the development's dramatic departures. So how does Beethoven bring us home?

30/ Already fortissimo (very loud), the music gets even louder (più forte) as a timpani roll leads to the moment we've all been waiting for (5:36). Or does it? What we get is "a magician's trick of high subtlety" (Lewis Lockwood): the most surprising double return ever written.

31/ F major returns in a double-fortissimo (fff) orchestral blaze (Donald Tovey calls it "noontide glare"). So does the opening theme, but not where you'd expect it. Instead of in the violins or high winds, it's low down in the bass, and something about the harmony is odd too.

32/ The timpani pounds out C, the most unstable note of the F major chord. The harmony only resolves eight bars later (5:44). At the same time the tune is buried in the bowels of the orchestra as a brand new melody blares out over the top of it. New material in a recapitulation?

33/ The theme is also shorter than it was at the start of the symphony; the middle woodwind phrase is missing, but immediately afterwards (5:44) the winds drive a presentation of the full 12-bar tune. So where does the recapitulation really start? Scholars still argue about it.

34/ Conductors have argued about it too. Greater musical minds than mine have tinkered with the scoring or dynamics in this passage to make the main theme more audible. But are Gustav's and Arturo's alterations actually missing Beethoven's point?

https://x.com/BeethovenAut/status/1315712136455368704?s=20

35/ The point is that passage "presents the elements of a recapitulation that undercuts it at the same time" (Lewis Lockwood). The return to stability is only partial, accompanied by surprise, uncertainty, even paradox, and a sense that the true homecoming is still to come.

36/ Once more Beethoven's dramatization of sonata form reaches its real climax in the extended coda (7:34). Starting like a second development section, it slips easy-as-you-please into D-flat, a key that should sound remote, but in fact feels surprisingly like coming home. Why?

37/ Because Beethoven has been preparing for it ever since his exposition skipped to the 'wrong' key via an 'errant' C-sharp that was the movement's first harmonic surprise. Now, as D-flat, the same note becomes the key that will finally restore order.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1316627782915502080?s=20

38/ Now when the main theme returns (7:53), it's loud and proud on the upper strings in the home key where it belongs, but it comes to rest on the dominant (8:02); we're not quite home yet. Astonishingly, it takes a triple-forte chord packed with D-flats (8:22) to get us home.

39/ The six-note motif joins hands with itself (8:25), alternating with three-note stabs over emphatic cadences that finally secure F major. Then the music dissolves (8:35) and the magician disappears through the door he came in, with a final statement of the six-note motif.

40/ The second movement (9:28) was long thought to be based on Beethoven's canon in praise of Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, who patented (but didn't invent) the metronome. However, the story and even the canon itself were a fraud perpetrated by Anton Schindler.

41/ Beethoven didn't know about metronome when he wrote this metronomic movement because the metronome wouldn't be invented until two years later; but he would have known the ticking clock movement that gives one of Haydn's last symphonies its nickname.

42/ Beethoven's big surprise is that the second movement isn't slow at all. He replaced the slow movement he originally planned to write with a short 'Allegretto scherzando' that playfully looks back both to Haydn and to Beethoven's own earlier music.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1240357012594143232?s=20

43/ As all music students know, 'Scherzo' means joke. As all students of Beethoven know, he replaced Haydn's courtly minuets with the muscular, dynamic scherzo. Like many things music students know, this is wrong. Haydn wrote plenty of scherzos himself.

44/ And some of Haydn's supposedly 'courtly' minuets have the muscular energy of Beethoven's scherzos if you play them at the tempo he asks for. Beethoven's next big joke is a 'Tempo di Menuetto' (13:47) third movement nothing like the scherzo we expect.

45/ Beethoven recalls his younger self, who wrote sets of minuets and other dances for noble patrons while making his name in Vienna. Discarding the five-part structure of symphonies 4, 6 and 7, he returns to the A-B-A form used by Haydn and Mozart.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1220759261271203840?s=20

46/ The trio section (15:55) looks back further still. Haydn often reduced the forces to spotlight horns and woodwinds. Beethoven does the same with a pair of horns and a solo clarinet forming a trio to remind us how this section first got its name.

47/ "An existential itch" (Tom Service) launches a finale (18:33) whose "quirks and surprises form the culmination of those of the earlier movements" (Lewis Lockwood) starting with the first movement's C-sharp (18:46) crashing in "like a drunken uncle at a party" (Jan Swafford).

48/ At first it only unites the orchestra behind the main theme, which continues at the C-sharp's fortissimo dynamic. But the first movement's jumping octaves also return in the bass (18:49) before the second theme, as in the first movement, arrives in the 'wrong' key (19:11).

49/ In the first movement the 'wrong' key was D, a minor third below the home key. Here it's A-flat, a minor third above. Relationships based on thirds were a feature of the Seventh symphony too, whose emphasis on F major seems to predict its successor.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1312281320056401921?s=20

50/ As in the first movement, the second theme slips easily onto the 'correct' key (19:21). When the existential itch returns (19:47) it looks like Beethoven will again follow in the footsteps of Haydn, who wrote many finales fusing sonata and rondo form.

But this isn't Haydn.

But this isn't Haydn.

51/ The development suppresses the C-sharp stab (19:59) with a new continuation, but as the octaves did before it finds a way to sneak back in. Held notes, first on the strong beat (20:11) then also the weak (20:15) are recognizable as its stabbing rhythm.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1311623793358635009?s=20

52/ Then a fiery statement of the main theme is interrupted by those octaves (20:41) "marking time but fragmenting orchestral space" (Tom Service) on bassoons and timpani. Had a symphony *ever* had timpani tuned in octaves before?

And people call this symphony old-fashioned.

And people call this symphony old-fashioned.

53/ The recapitulation sees C-sharp reappear in what now feels like its rightful place (21:00). Its return starts to have consequences: the second theme (21:37) now starts in D-flat (= C sharp) before the home key is restored. If this was Haydn we'd be putting our coats on now.

54/ But as every music student knows, Beethoven has spent his career shifting the weight of his musical arguments from the beginning of a piece to the end. We still have another development section (22:10) and recapitulation (23:26) to go before we can even think about a coda.

55/ An alien C-sharp began the symphony that announced Beethoven's Heroic Style. Now that same surprising note returns to help him close the last symphony of his middle period. After 8 symphonies in 12 years, it takes him 12 more years to complete a 9th.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1274608885085736960?s=20

56/ Surprise is no longer adequate and we are forced to resort to astonishment when "the drunken uncle runs amok" (Swafford) in the second recapitulation, notated first as D-flat (23:39) then as C-sharp (23:41) to derail us into F-sharp minor when F major should be rock-solid.

57/ The trumpets (who can't play C-sharp) wrench the music back on track (23:54) and now the second theme is presented entirely in the home key (24:07) with no deviations towards unknown harmonic regions. The drunken uncle's next outburst is no longer C-sharp but E-flat (24:27).

58/ As the coda at last hammers home the home key it finds space (24:49) to create "a Klangfarbenmelodie, a melody of changing orchestral colour, a century before Schoenberg and Webern" (Tom Service), one last weirdness in one of the weirdest, most surprising symphonies of all.

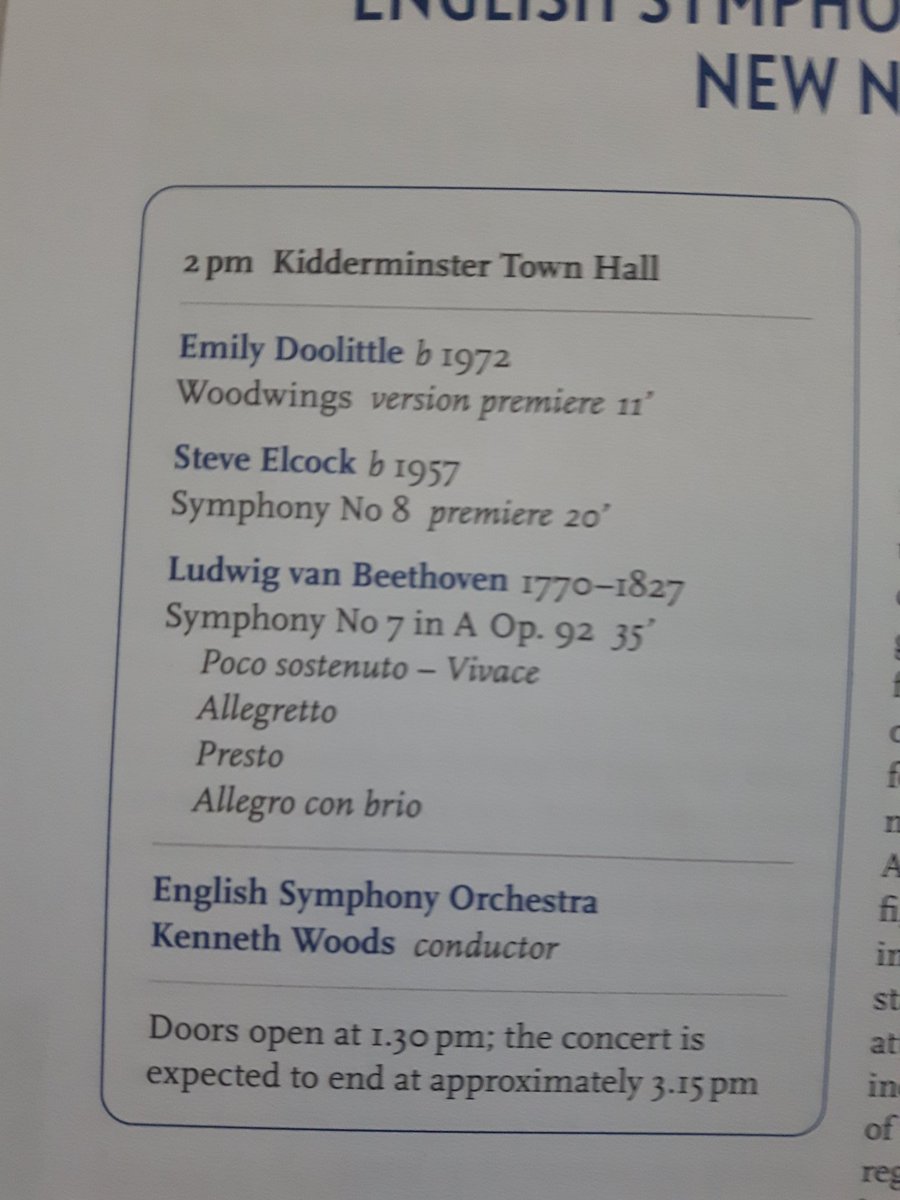

59/ If Beethoven expected its "superficially conventional appearance" (Barry Cooper) to ingratiate "my little Symphony in F" with his audience he was mistaken. It was premiered on 27th February 1814 alongside Symphony No. 7 and 'Wellington's Victory'.

https://x.com/deeplyclassical/status/1317742386865463297?s=20

60/ Those works had caused a sensation in Vienna but, according to early reviewers ,the audience were baffled by No. 8: "in short - as the Italians say - it did not create a furor."

When his pupil Carl Czerny asked why, Beethoven replied: "because the Eighth is so much better."

When his pupil Carl Czerny asked why, Beethoven replied: "because the Eighth is so much better."

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh