My thoughts from this new @timeshighered piece: “We need to trust students to be partners in shaping the future of their own education. This means we can’t begin with the belief that our job is to rank them against one another or police their learning.” timeshighereducation.com/opinion/teachi…

More of my thoughts from the interview:

We need to carefully examine our approaches to grading, marking, and assessment. So much of our system is mired in one skewed approach to assessment, which focuses on quantitative, standardized, and supposedly objective marks.

We need to carefully examine our approaches to grading, marking, and assessment. So much of our system is mired in one skewed approach to assessment, which focuses on quantitative, standardized, and supposedly objective marks.

There is very little wiggle room for teachers to challenge the systems for assessment in higher education and very little relief for marginalized students who are not well-served by these systems.

Accreditors, administrators, faculty, students, graduate admissions boards aren't really talking to one another, so it’s become nearly impossible to make change in one part of the system without running aground on a series of bureaucratic hurdles in some other part of the system.

And almost no one, especially students, feels empowered to ask hard questions about the whats, whys, and hows of assessment.

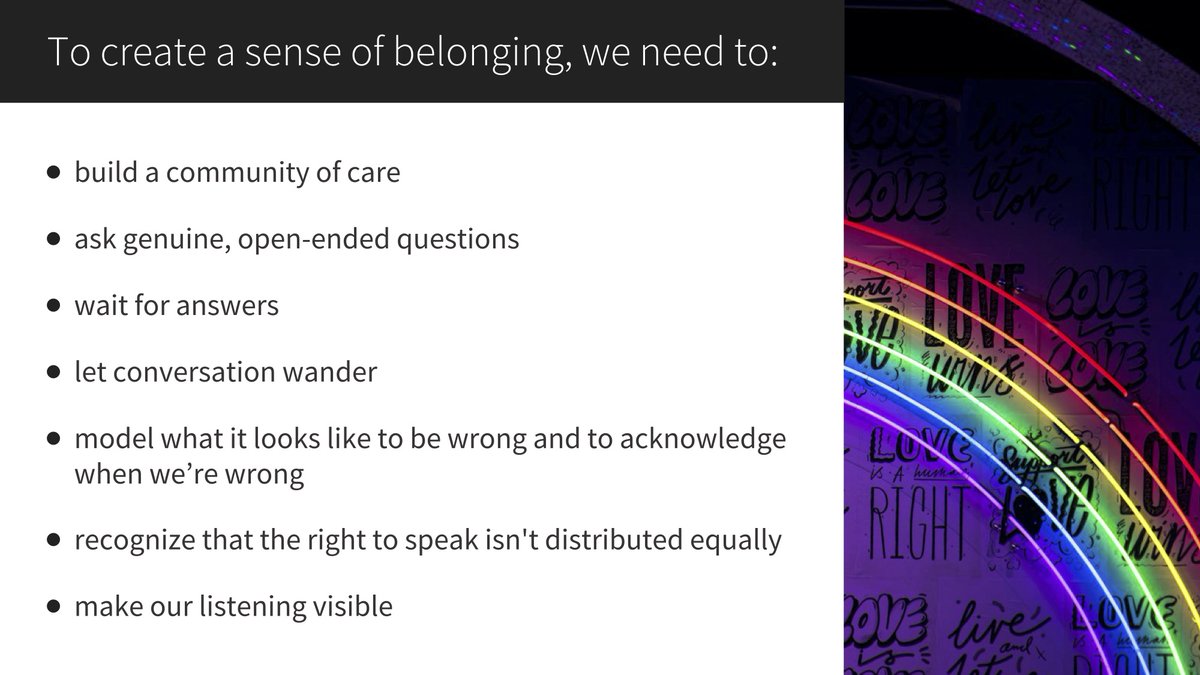

We need to start with really basic questions: Who is assessment for? How can assessment better support student learning? How can we engage students more fully in conversations about their own education, bringing them into the design of courses, curricula, and assessment?

We need to start our work from the presumption that students are humans first, not rows in a spreadsheet. Any of our efforts will be frustrated if we don't let go of broad assumptions that students lack integrity. Students as a group are not, by nature, cheaters or plagiarists.

The discussion around compassionate approaches to assessment amidst COVID-19 has unearthed deeper problems and inequities across higher education. We need to address the needs of students and faculty right now, while also looking toward more long-lasting systemic change.

Students are currently experiencing acute trauma, and the effects of that trauma won't go away suddenly or magically. There will not be a day when we can simply "pivot" back to business as usual.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh