This Day in Labor History: October 14, 1840. Proceedings began in Commonwealth v. Hunt, a critical early legal case that, two years later, established the right of workers to strike in the United States!!!!

Early American law basically banned the right to strike. This drew from British law that saw any combination that restrained trade as illegal.

Whether workers striking was in fact a combination is a whole other question and pretty dubious, but this went back at least to a 1721 English case. In 1806, a Pennsylvania case, Commonwealth v. Pullis, drew on that British tradition to rule a strike such an unlawful combination.

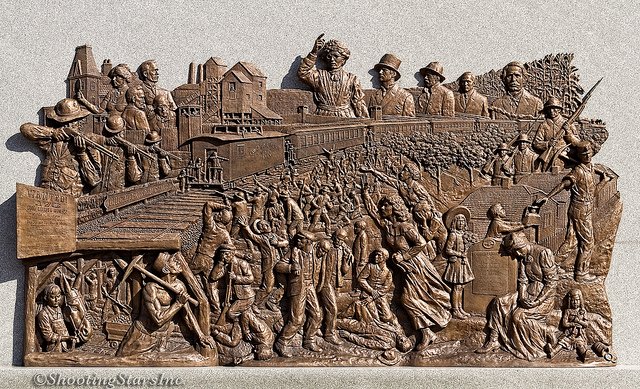

At the same time, the Industrial Revolution was transforming the United States. Work changed seemingly overnight from a rural economy supported by urban artisans who mostly controlled the conditions of their labor in their trade to the rise of the industrial proletariat.

Work became more dangerous and workers slowly started losing control over their lives. The dreaded industrialized cities of Britain such as Manchester were repeating themselves in America. Life was pretty rough.

And the courts did not allow workers to engage in the critical action that would allow them to improve their lives–the withholding of their labor to gain power.

Between 1806 and 1842, there were 17 conspiracy convictions against workers for striking.

That didn’t mean that every strike went to court–there were certainly more than 17 strikes in these 36 years and some of them were pretty important, such as the Paterson textile strike in 1835 and Baltimore seamstresses walking off the job in 1833.

But there was strong legal precedent on the matter.

When the state sought to prosecute another set of workers in 1840, it seemed perhaps that an 18th conviction was inevitable. However, that was not the case. Commonwealth v. Hunt originated with the Boston Journeyman Bootmakers’ Society, an early craft union.

A worker named Jeremiah Horne agreed to do extra work on a pair of boots without charging for his labor. The Society fined Horne. He refused to pay, but his master did.

ut Horne was a jerk and kept breaking the rules. Finally, the Society demanded the master fire him and he did. Horne went to the Suffolk County Attorney to complain.

He decided to prosecute the Bootmakers’ Society for unlawfully engaging in a criminal conspiracy to impoverish non-union members and their bosses. The trial began on October 14, 1840 and ended eight days later.

The Bootmakers had a strong defense, crafted by the leading Boston Democrat Robert Rantoul, who made a case that such combinations were common and unexceptional.

The judge, Peter Oxenbridge Thacher, was however a rabid pro-business conservative Whig and told the jury that such actions would “render property insecure, and make it the spoil of the multitude, would annihilate property, and involve society in a common ruin.”

So the workers lost. But they appealed and the case went to the Massachusetts Supreme Court.

Judge Lemuel Shaw ruled on the appeal. He wrote, “We cannot perceive, that it is criminal for men to agree together to exercise their own acknowledged rights, in such a manner as best to subserve their interests.” Now, Shaw was hardly a pro-worker judge.

A mere one week earlier, his ruling in Farwell v. Boston and Worcester Rail Road Corporation created the precedent that employers had no responsibility for workplace safety or anything else concerning workers since they had chosen to work that job.

In short, it laid the foundation that would get reinforced seven decades later in Lochner. But in this case, he ruled in a reasonable manner.

It wasn’t a sweeping victory for workers. This only applied if their actions remained legal and their ends reasonable. Basically, it means-tested each strike and so long as it stayed within proper boundaries, that was OK.

In other words, strikes for wages and hours might well be legal but strikes to challenge capitalism were not.

Shaw took Rantoul’s legal reasoning almost fully, noting that there were no laws in Massachusetts against raising wages and so the appeal to English common law where there was precedent for that was irrelevant.

Some have speculated that Shaw, a Whig himself, made a politically expedient decision and didn’t want to have a riled up Boston working class voting overwhelmingly for Democrats in the 1844 election.

In any case, we don’t really know why he gave labor a rare favorable ruling that so clearly articulated the right to strike.

In fact, while Shaw was the first major jurist to articulate this as a legal principle, it had been seen in practice on many occasions.

While all of those conspiracy convictions certainly were a threat, on many cases, prosecutors simply chose not to go in that direction, such as the ten-hour day strikes in Boston in 1836 and 1837.

Or even if they did, a grand jury might reject the strategy entirely, which is what happened in Philadelphia in 1836 when coal-heavers walked off the job and then the city’s trade unions, 20,000 strong, joined them in support.

If anything was a clear combination in restraint of trade it was that, but sympathetic juries often ignored these principles in favor of common sense.

Moreover, even when there were convictions, most courts were pretty lenient on the workers. In Commonwealth v. Pullis, the guilty strike leaders were fined $8.

Shaw’s ruling in Commonwealth v. Hunt was critical but also existed in a nation where conditions for strikers were actually not that bad compared to what would come after the Civil War.

Even before his ruling, military or police attacks on strikers were rare, albeit not unknown.

But as a rule, the forces of order allowed strikes to go on and it was only in the 1870s that militarized state forces became an acceptable tool of the capitalist class to suppress workplace rebellion.

By that time, judges were also once again using conspiracy convictions to repress workers’ rights. It was hard for labor to win anything when the state combined with business to repress any action workers took.

This thread drew from Joshua Lambert’s 2005 book “If the Workers Took a Notion”: The Right to Strike and American Political Development, published by Cornell University Press, as well as from the American Legal History wiki project.

Back tomorrow to discuss the Clayton Act!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh