#HistoryKeThread: The Man Who Built Chiromo

Once there lived a man in Kenya - a man born to break rules. And norms. And records.

Once there lived a man in Kenya - a man born to break rules. And norms. And records.

He was as daring as he was rebellious to authority. Yes, a bully even.

His name was Ewart Scott Grogan, the 14th of 21 children of William Grogan.

His name was Ewart Scott Grogan, the 14th of 21 children of William Grogan.

One morning in March 1907, Grogan severely flogged three of his black servants - one of whom died of his injuries - outside the Nairobi courthouse for subjecting his visitors to a rough rickshaw ride.

For taking the law into his hands, Grogan was subsequently jailed by the authorities, a move that shocked the settler community.

The settlers found it difficult to come to terms with the white administration jailing one of their own, the President of the Colonists Association no less.

But Grogan’s brush with authorities had started much earlier.

Two London institutions of learning in which he was enrolled expelled him. He therefore didn’t complete studies at his last institution, reportedly @JesusCollegeCam, in Cambridge, United Kingdom.

By 1896, Grogan had read several books by Sir Henry R. Haggard, who had a penchant for authoring adventurous fictions set on Africa, such as King Solomon’s Mines.

These books so ignited in Grogan a passion for the so-called dark continent that he set out that year, aged only 22, to Cape Town, South Africa.

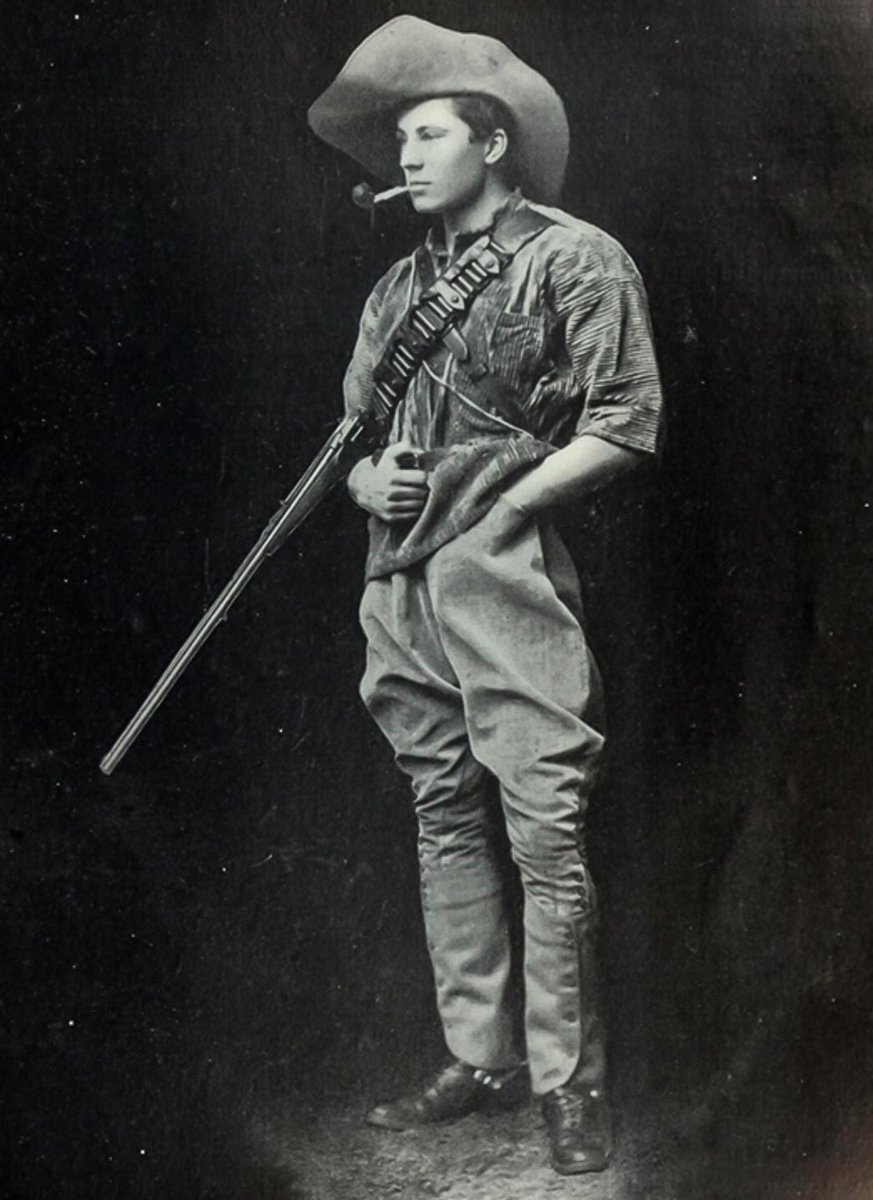

And no sooner had he landed in South Africa than he enlisted to serve in the second Matabeleland war pitting the British South African Company‘s maxim guns against the battle axes, assegais and a sprinkling of rifles (thanks to defecting askaris) of the Matabele warriors.

During the war, Grogan fought alongside, and befriended, Cecil Rhodes.

It is likely Grogan suffered PTSD in the peacetime that followed. It is recorded that the long sea voyage to New Zealand he embarked on afterwards was intended to help him shake off the trauma and horrors of the Matabele war.

But if he needed a shoulder to cry on in New Zealand, there arguably wasn’t anything better that lady luck would find him than Gertrude Edith Watt, a beauty and heiress.

Gertrude’s stepfather growled at the young Briton, terming him a fortune hunter who was not worthy of his daughter’s hand in marriage. Grogan was warned that he wouldn’t marry Gertrude unless he proved himself.

At that juncture, the young man, perhaps spreading out on a large table a map of Africa featuring illustrations of wild game and armed tribes, pompously offered, for Gertrude’s hand in marriage, to “become the first man to trek from Cape Town to Cairo”.

Well, trek from Cape Town to Cairo Grogan nearly did. Nearly because in Sudan, two years into his trek and close to dying of fever, he fortuitously stumbled on a British expeditionary group on a Nile steamer, on which he sailed for the rest of the trip to Cairo.

At that point, Arthur Sharp, Gertrude’s uncle who had accompanied Grogan on the trek, had long quit the challenge.

The steamer ride must have ended too quickly for those onboard to have heard half the tales that Grogan had to tell.

For his feat, Ewart Grogan became the youngest man to not only be inducted as a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, but to also address its members.

For his feat, Ewart Grogan became the youngest man to not only be inducted as a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, but to also address its members.

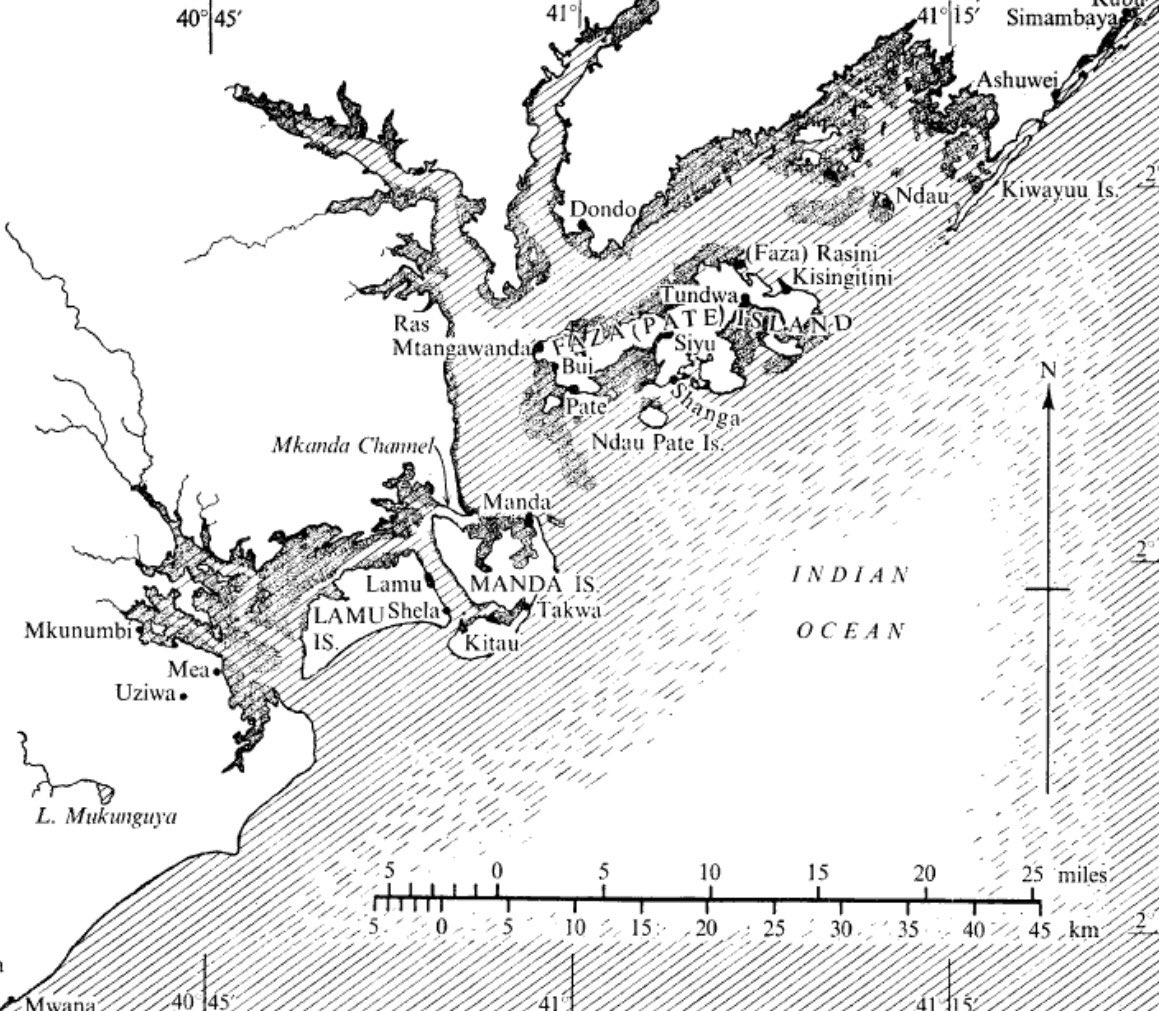

In 1904, Grogan and his wife Gertrude settled in Kenya. The couple owned large tracts of land around Nairobi, including the Torr’s hotel and a “palace” they built near the banks of Nairobi River, and which they named Chiromo. This part of Nairobi bears the name to this day.

Apart from putting up a pediatric hospital named after Gertrude - the Gertrude’s Children Hospital, they also owned sisal estates and a vacation home in Taita Taveta.

Kirinyaga Road in downtown Nairobi was previously named Grogan Road, and many till today still refer to the area famous for its many spare parts shops as “Grogan”.

Gertrude died on 6th July 1943, aged 66. Her husband died in 1967, aged 93.

Gertrude died on 6th July 1943, aged 66. Her husband died in 1967, aged 93.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh