Let's do dispersion trading for the uninitiated.

The vets will need to bear with me, it's been 20 years since i traded index anything...but that actually shows why it's a good thing to explain. The lessons from it come to bear on thinking about all portfolios, even today.

The vets will need to bear with me, it's been 20 years since i traded index anything...but that actually shows why it's a good thing to explain. The lessons from it come to bear on thinking about all portfolios, even today.

First what is dispersion trading?

In its purest form, imagine selling an index straddle and buying the components' straddles in proportion to the index weights. In practice, liquidity makes this impossible. Instead one settles for a "dirty dispersion" position.

In its purest form, imagine selling an index straddle and buying the components' straddles in proportion to the index weights. In practice, liquidity makes this impossible. Instead one settles for a "dirty dispersion" position.

The trade is "short correlation". It wants the average corr between the stocks in the basket to be as low as possible.

Imagine a 2 stock index. You own the straddles on the stocks and you are short the index straddle. The 2 stocks rip in opposite directions. The index is unch

Imagine a 2 stock index. You own the straddles on the stocks and you are short the index straddle. The 2 stocks rip in opposite directions. The index is unch

That's a homerun! You win on every leg. You win on the call leg of one stock's straddle, the put leg of the other stock's straddle and the index doesn't go anywhere allowing you to collect on the full short premium.

Now let's move to the opposite scenario.

Now let's move to the opposite scenario.

The stocks move exactly together in a big way. You win on your stock straddles but you will lose more on your index short.

Why?

The index is cheaper than the sum of the legs in straddle space.

We will need an intuitive equation to understand that.

Why?

The index is cheaper than the sum of the legs in straddle space.

We will need an intuitive equation to understand that.

3 terms:

Index variance

Avg stock variance

Avg cross corr of each stock to every other stock

The equation:

Index variance = avg stock Variance x Avg Corr

perhaps more intuitive:

Avg corr = index variance / avg stock variance

Unless corr is 1, index var < stock var!

Index variance

Avg stock variance

Avg cross corr of each stock to every other stock

The equation:

Index variance = avg stock Variance x Avg Corr

perhaps more intuitive:

Avg corr = index variance / avg stock variance

Unless corr is 1, index var < stock var!

It bears repeating...the avg corr is the ratio of index var to stock var. So if index var is trading for 50% of the var of the avg weighted stock vol then the implied cross correlation is .50

Be careful, you need to take square roots to move from var space to vol space.

Be careful, you need to take square roots to move from var space to vol space.

It follows that if you square the ratio of index vol to stock vol you get the implied corr.

So if the index vol is 20% and the avg weighted stock vol is 30% then implied corr = (.2/.3)^2

Implied corr = .44

Let's talk correlation risk...

So if the index vol is 20% and the avg weighted stock vol is 30% then implied corr = (.2/.3)^2

Implied corr = .44

Let's talk correlation risk...

If stock vols are constant, and index vols increase, implied corr is increasing. Likewise, if correlation surges the spread of index vol to stock vols must be narrowing (at corr = 1 they would converge)

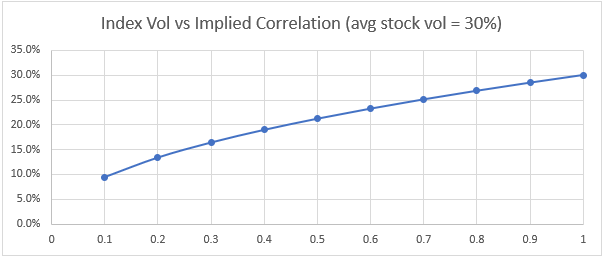

Here's index vol relation to corr for a fixed stock vol of 30%

Here's index vol relation to corr for a fixed stock vol of 30%

Dispersion is tricky.

If you structure the trade vega neutral or premium neutral you will be short correlation convexity.

As corr ⬆️: you get shorter vol as the index short will grows faster than the stock vol longs

As corr ⬇️: vice versa. Getting longer vol as it falls

If you structure the trade vega neutral or premium neutral you will be short correlation convexity.

As corr ⬆️: you get shorter vol as the index short will grows faster than the stock vol longs

As corr ⬇️: vice versa. Getting longer vol as it falls

You are short corr (in other words, taking a similar risk premia as any risk-on position) and your position size has neg gamma with respect to changes in corr.

You may choose to overweight stock long vega to flatten the curvature, but now you increase exposure to owning options

You may choose to overweight stock long vega to flatten the curvature, but now you increase exposure to owning options

There is a lot of room for creativity in how you structure these trades. What you want your local gamma/theta profile to be, how much basis or synthetic basket risk you want to take with names you include or not since this is a "dirty" trade in the first place, etc etc.

Lessons that can be ported into less niche strategies:

The risk for any long/short trades in any portfolio of delta one or vol positions is as correlations increase your gross positions become exposed.

You can't hide behind "nets" when corrs explode higher.

The risk for any long/short trades in any portfolio of delta one or vol positions is as correlations increase your gross positions become exposed.

You can't hide behind "nets" when corrs explode higher.

Imagine a beta neutral trade where you are long 2 units of "alpha stock" and short 1 unit of index (assume they are the same vol, but "alpha" stock is .50 corr)

When corr ⏩ 1 you are no longer neutral but long equiv of 1 unit of index into a falling market, increasing corr mkt

When corr ⏩ 1 you are no longer neutral but long equiv of 1 unit of index into a falling market, increasing corr mkt

Relative value books tend to blow up as corrs increase since corrs are used to weight positions.

A portfolio therefore that wins as corr (which is itself correlated with equity risk premia) increases should cost carry!

A portfolio therefore that wins as corr (which is itself correlated with equity risk premia) increases should cost carry!

And in fact this is what we find…implied correlation trades at a premium to realized correlation. You pay a premium to hold that position and the dispersion trade is a source of carry correlated with conventional risk premia.

If you put the 3D options glasses back on, you see:

If you put the 3D options glasses back on, you see:

That source of carry has its own correlation skew across the surface…upside implied correlations are cheaper than downside correlations.

Implied correlation has a term structure as well.

Implied corrs are everywhere across the surface...and across sectors too...

Implied correlation has a term structure as well.

Implied corrs are everywhere across the surface...and across sectors too...

Implied correlation can be measured for sector indices. Energy, biotech, bank etfs. All have implied correlations between basket components.

Then consider FX vol markets and how they care about the rate vols of the individual legs and, you guessed it, the correlation.

Then consider FX vol markets and how they care about the rate vols of the individual legs and, you guessed it, the correlation.

How about a US investor trading options on a foreign index of an exporter nation. Like Japan. There's an implied correlation between the yen and the equity index itself.

How do implied correlations correlate to systematic risk premia? How do they compare to realized corrs?

How do implied correlations correlate to systematic risk premia? How do they compare to realized corrs?

These types of questions are the start of seeing the world as one big spiderweb of risk premia and cross correlations.

Now go build the dashboard to find the cheapest hedges, the most efficient basis, or the most levered shot at a skewed assumption of a correlation persisting.

Now go build the dashboard to find the cheapest hedges, the most efficient basis, or the most levered shot at a skewed assumption of a correlation persisting.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh