“Will there be a vaccine in 2020?” is a question I wish I could have asked an ancient Babylonian or Assyrian seer in March to assuage anxiety, manage expectations, or make decisions.

Thread on using the organs of sheep to answer specifically worded questions a long time ago

Thread on using the organs of sheep to answer specifically worded questions a long time ago

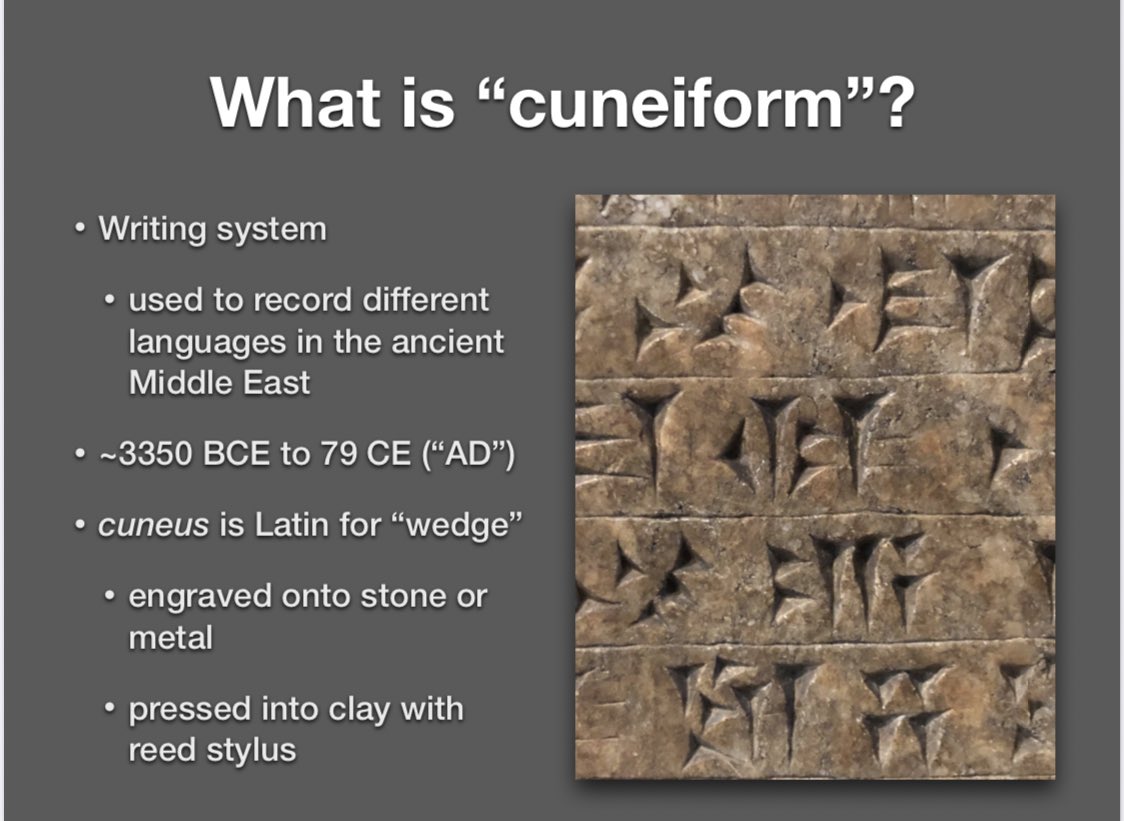

Nature was a clay tablet to the diviner in ancient Mesopotamia. The gods inscribed signs in astronomical phenomena, animal behaviour, plant life, oil, smoke, human physiology, dreams, and animal exta to be read by diviners.

The liver was sometimes called the tablet of the gods.

The liver was sometimes called the tablet of the gods.

There is a fancy word in English for liver divination that took me ~3 years to learn to spell: extispicy.

In ancient Mesopotamia, this was the job of the bārû, "seer" or "diviner". A person trained for a Very Long Time to learn to read signs inscribed on the entrails of sheep

In ancient Mesopotamia, this was the job of the bārû, "seer" or "diviner". A person trained for a Very Long Time to learn to read signs inscribed on the entrails of sheep

If you lived in ancient Mesopotamia, were royalty or could afford it, and had anxiety about the future, you could turn to a professional diviner to answer a specifically worded question with a favourable or unfavourable response.

In other words, yes or no questions only please

In other words, yes or no questions only please

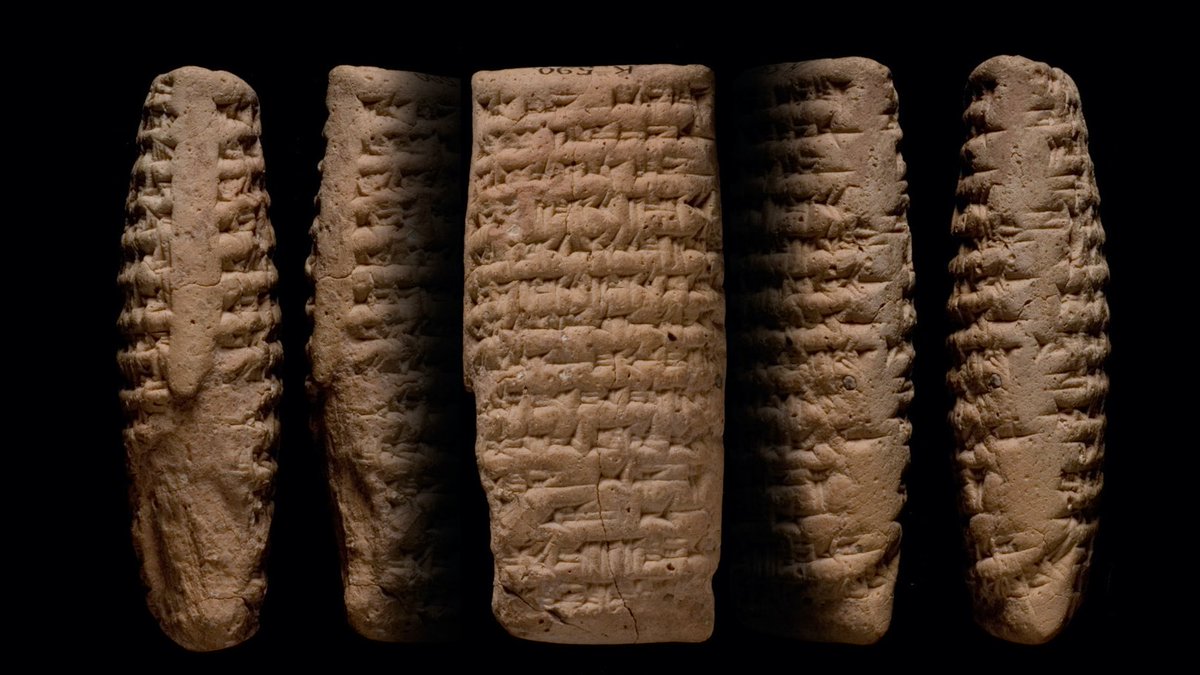

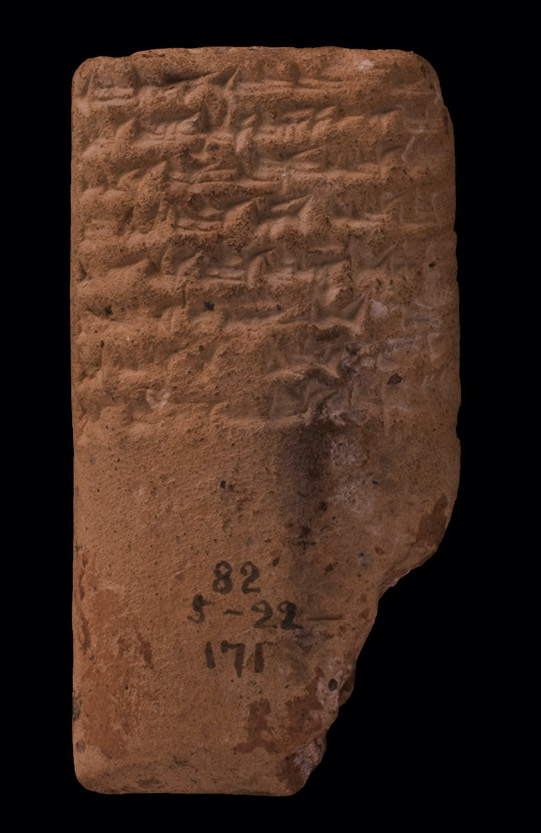

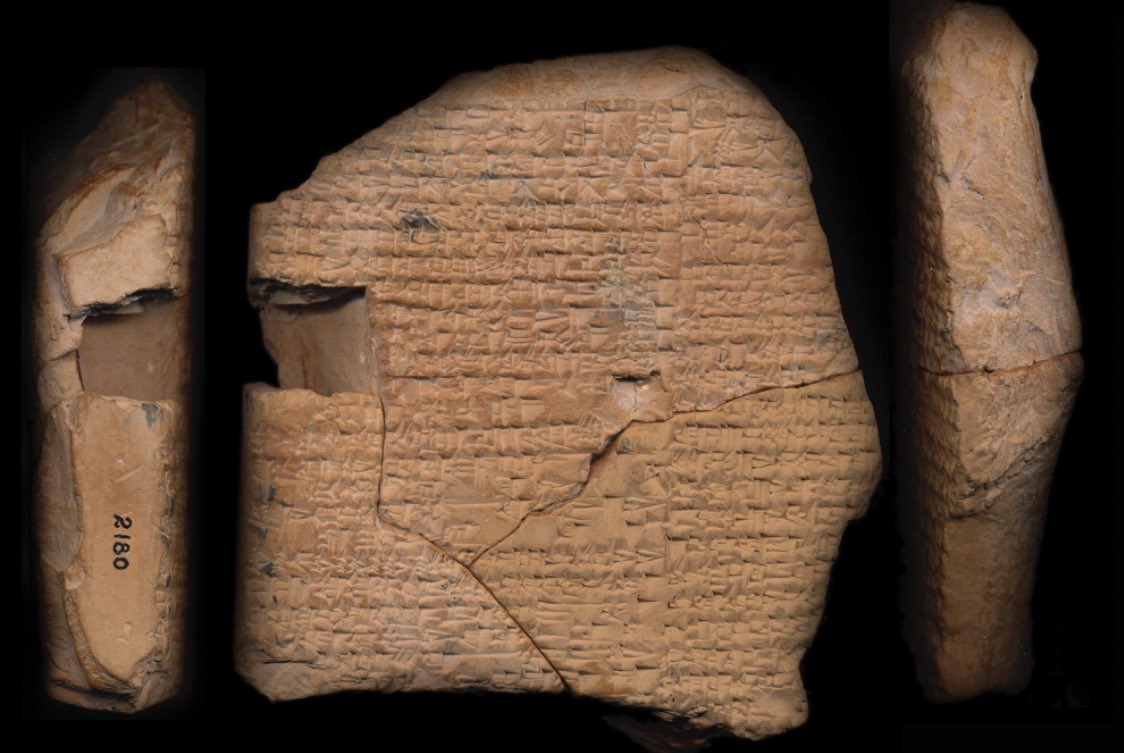

Letters from clients requesting divination and diviners to kings and state officials about divination, divinatory reports, compendious textbooks of omens–all written on clay–survive from ancient Mesopotamia to tell the stories of those in search of answers to their questions.

A man named Qurdusha in the ancient city of Mari in the early second millennium BCE writes, “Take a lamb from my flock to the diviner to decide on my cattle and flocks.”

“Will the Elamite army gather, get organized, march, (and) fight with the men and army of Assurbanipal?” an ancient Assyrian king asks a diviner mid-war.

(…The answer was no) oracc.iaas.upenn.edu/saao/saa04/P23…

(…The answer was no) oracc.iaas.upenn.edu/saao/saa04/P23…

Iltani, a Babylonian queen, asks a diviner named Aqba-hammu about whether a young man will recover from an illness, possibly epilepsy. She sent cuts of his hair and clothing for the ritual.

“I took omens over the lock and fringes, and they are favourable” was the reply.

“I took omens over the lock and fringes, and they are favourable” was the reply.

To answer a query, a Babylonian diviner begins with a ritual to present a question to the gods. Sometimes, this would be written on a clay tablet, but it could also be whispered into the ear of the sheep to be sacrificed.

On that sheep’s innards, the answer would be written.

On that sheep’s innards, the answer would be written.

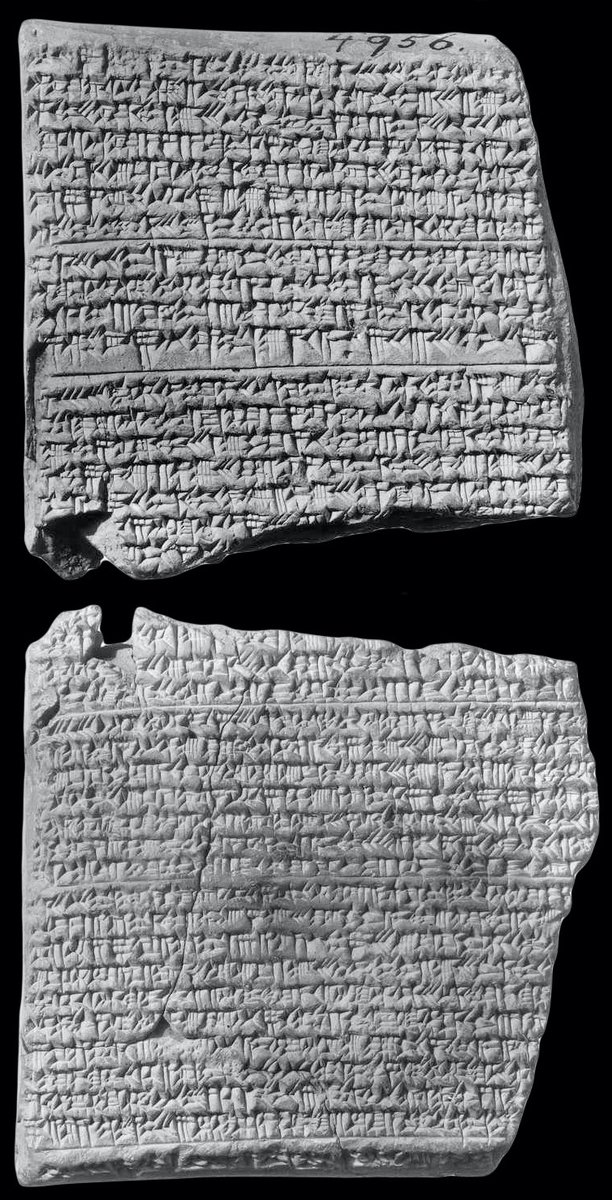

One tablet from ancient Sippar shaped like a liver divides it into sections and lists marks and their interpretation. A blemish in one area means “A hidden army will scatter”. In another, “The god Adad will thunder in the land.”

"Reading" a liver was complicated and specific.

"Reading" a liver was complicated and specific.

Link to the subdivided, complicated, and extremely cool Old Babylonian liver tablet britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

Babylonian and Assyrian diviners who interpreted signs in exta learned from collections of omens that read as if-then statements.

“If a Foot-mark is displayed on the left of the lung: the enemy’s Foot-mark; sorrow; the enemy will get what he wants” oracc.iaas.upenn.edu/cams/barutu/P2…

“If a Foot-mark is displayed on the left of the lung: the enemy’s Foot-mark; sorrow; the enemy will get what he wants” oracc.iaas.upenn.edu/cams/barutu/P2…

Omens involving organs used really specific terminology for their parts, like “the path”, “the presence”, “the palace gate”, “the finger”, “the increment”, where blemishes or marks might be observed.

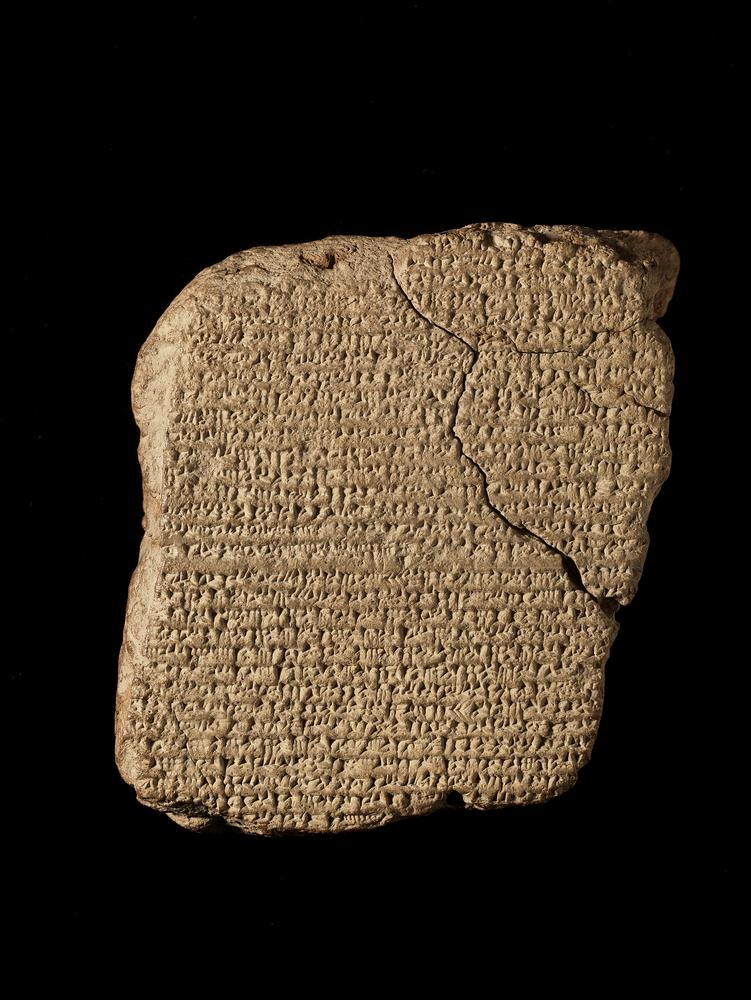

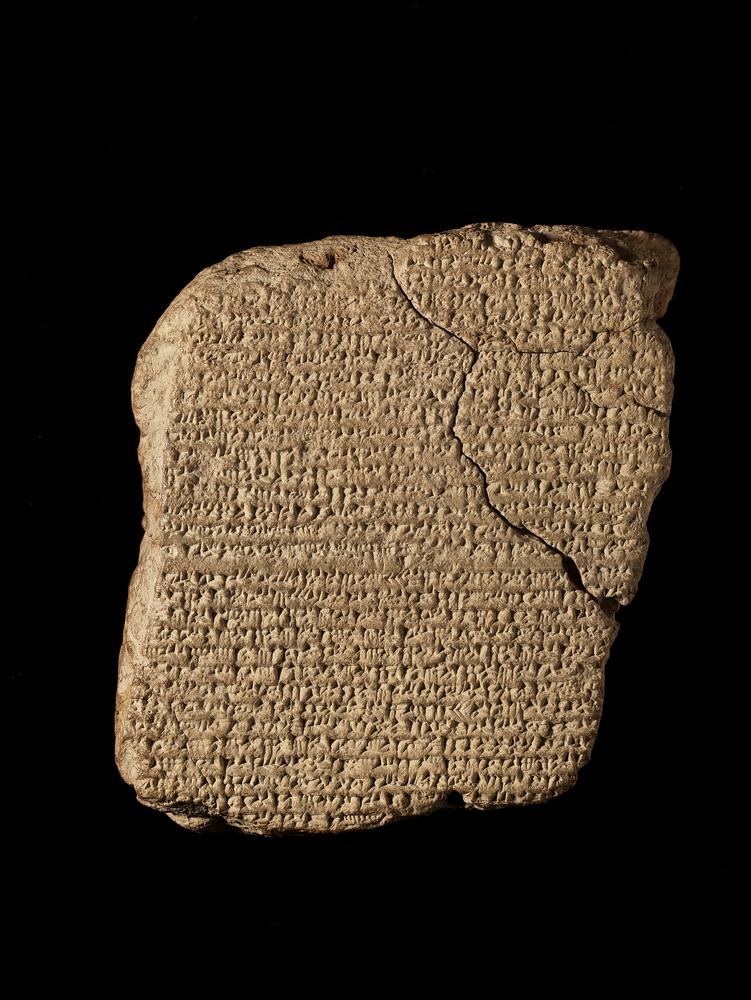

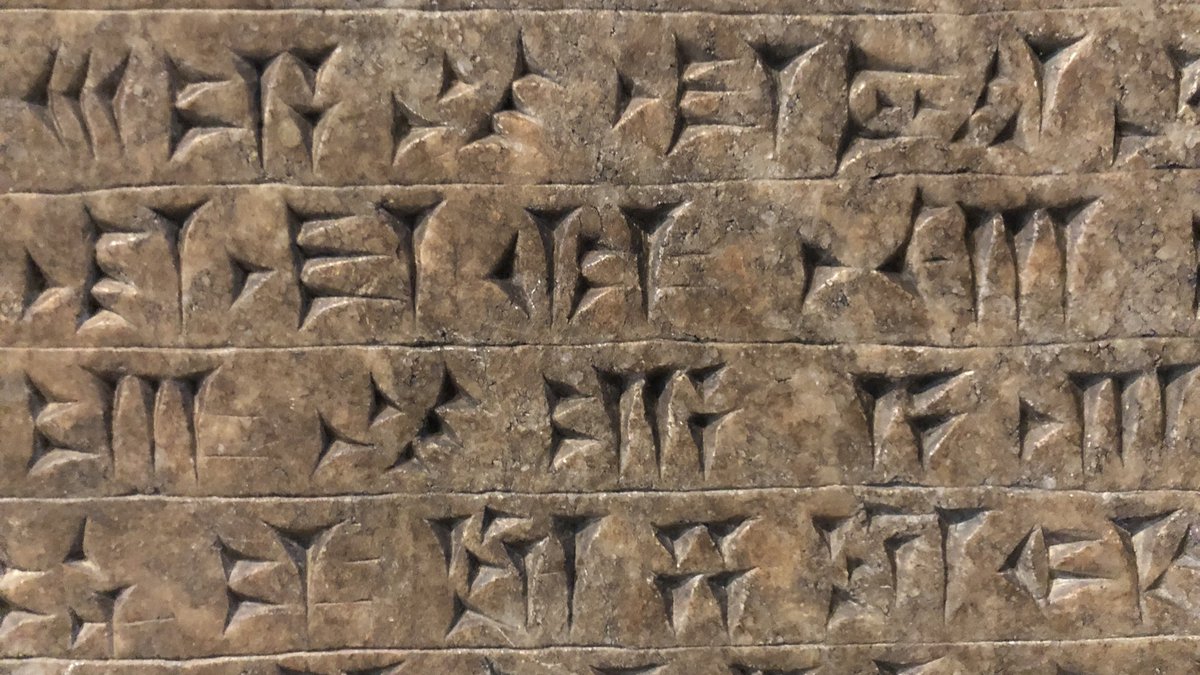

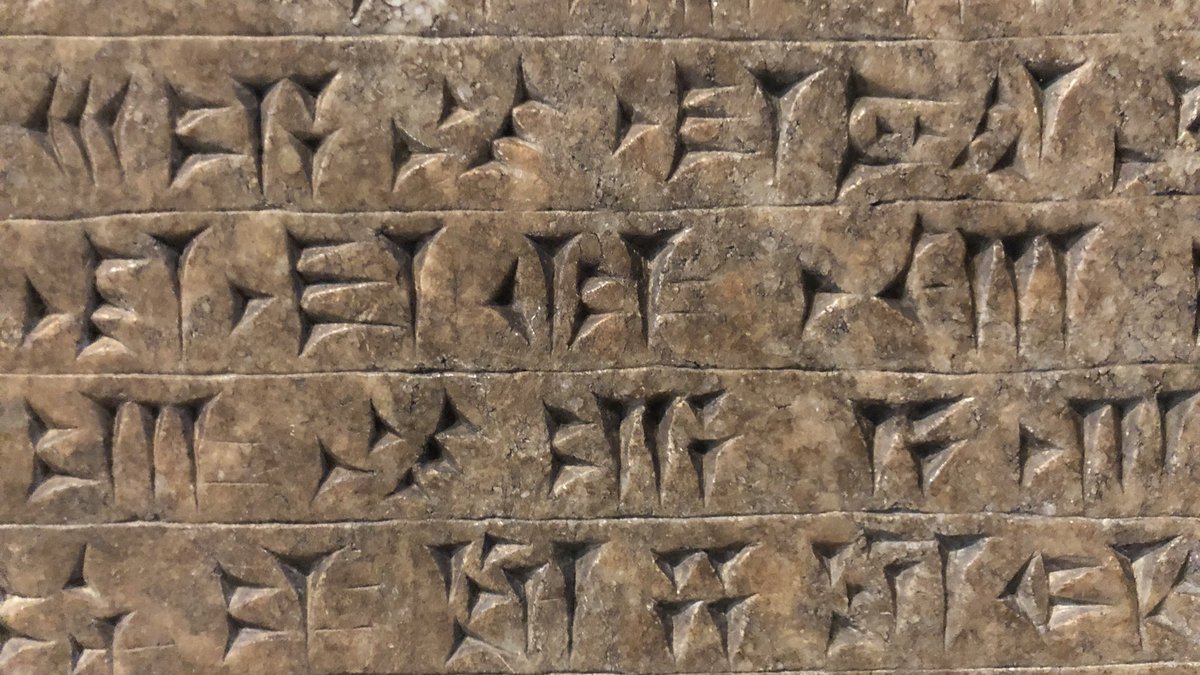

Here are some on a liver model from Mari composed in the 2nd millennium BCE

Here are some on a liver model from Mari composed in the 2nd millennium BCE

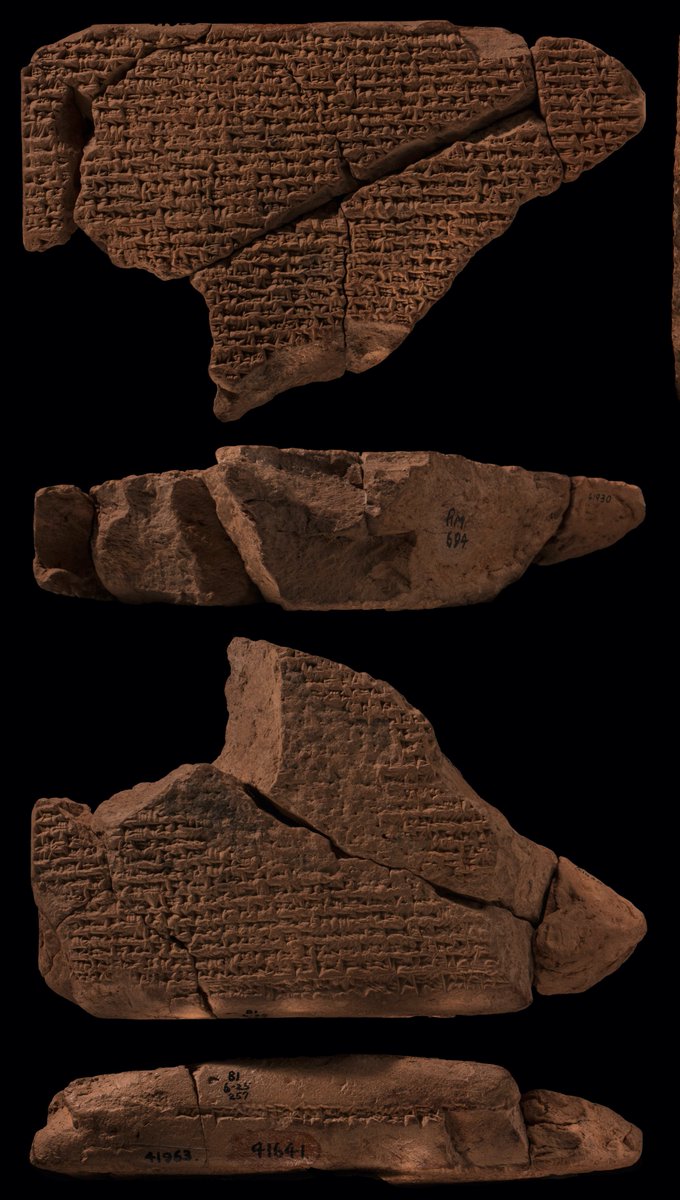

Babylonian diviners sometimes made clay models of livers and other internal organs they observed, like the coils of an intestine, to record their reports or display the appearance of exta, shapes and marks and all, when a particular event was observed.

A Babylonian model of intestinal coils takes the shape of the face of the demon Humbaba.

The cuneiform on the back reads, “If the coils of the intestine look like the face of Humbaba, this is the omen of Sargon who ruled all the lands...” Signed by the diviner Warad-Marduk

The cuneiform on the back reads, “If the coils of the intestine look like the face of Humbaba, this is the omen of Sargon who ruled all the lands...” Signed by the diviner Warad-Marduk

Basically each omen had either a negative or positive value. If liver's feature implied e.g., famine, that was –. If it implied e.g., victory in battle, that was +.

Diviners would tally up the +’s and –‘s to determine their answer to the original yes or no query.

Diviners would tally up the +’s and –‘s to determine their answer to the original yes or no query.

If you were a leader in ancient Mesopotamia, divination was a useful tool for helping with political decisions. In the Babylonian city of Mari in the early second millennium BCE, kings regularly consulted diviners in matters of state and war. Ditto for Assyria 1,000 years later.

Divination that relied on internal organs like livers were provoked and expensive, bearing the cost of the full animal(s).

More affordable methods of provoked divination included oil and smoke omens, but they were rarely written down.

More affordable methods of provoked divination included oil and smoke omens, but they were rarely written down.

Unprovoked omens deserve a thread of their own and include observations of any naturally occurring thing, from the position of a mole on a person’s face to the position of Venus in a particular constellation.

Though we may not have been able to start the year with liver divination to find out what the end of 2020 would bring, we can know that we aren’t alone in our anxiety about the future and desire for ways to decide it and know it, even when things feel totally out of our control.

The outcome of a battle (or vote), the course of a disease, or the end of a pandemic – the only real certainty is uncertainty, but we have always done what we need to do to get by while we wait to see what the future holds, whether it's 2020 BCE or today...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh