As Chinese officials hung thousands of cameras across Xinjiang, an abiding question has been how they process all that footage. We found an answer. They're using one of the world's fastest supercomputers. And it was built with American microchips. nytimes.com/2020/11/22/tec…

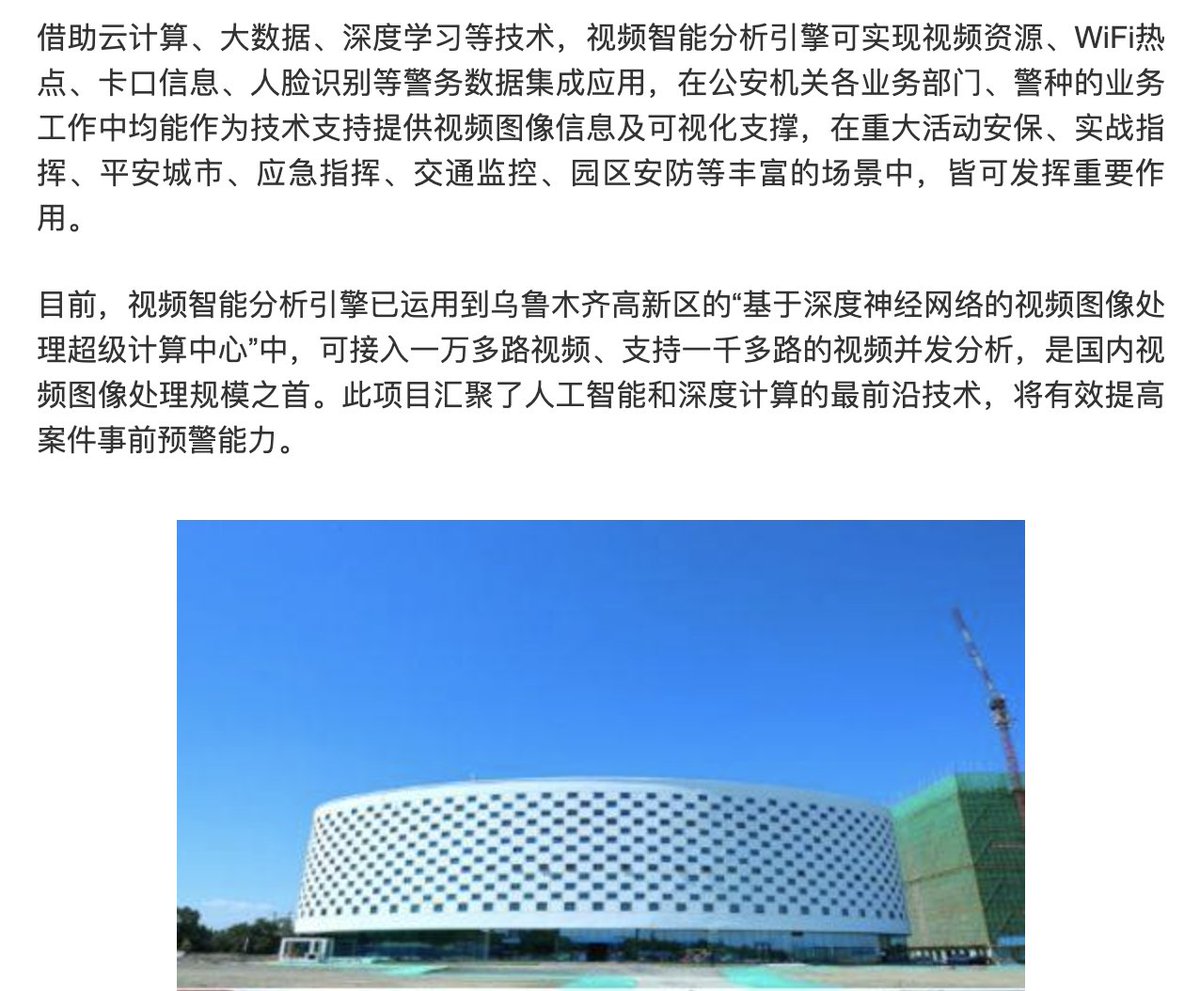

The supercomputer center is as bleak a symbol of dystopian tech as you can imagine. It sits at the end of a forlorn road that passes six prisons. The machines, powered by Intel and Nvidia, line the inside of a strange oval-shaped building with an inexplicably green lawn.

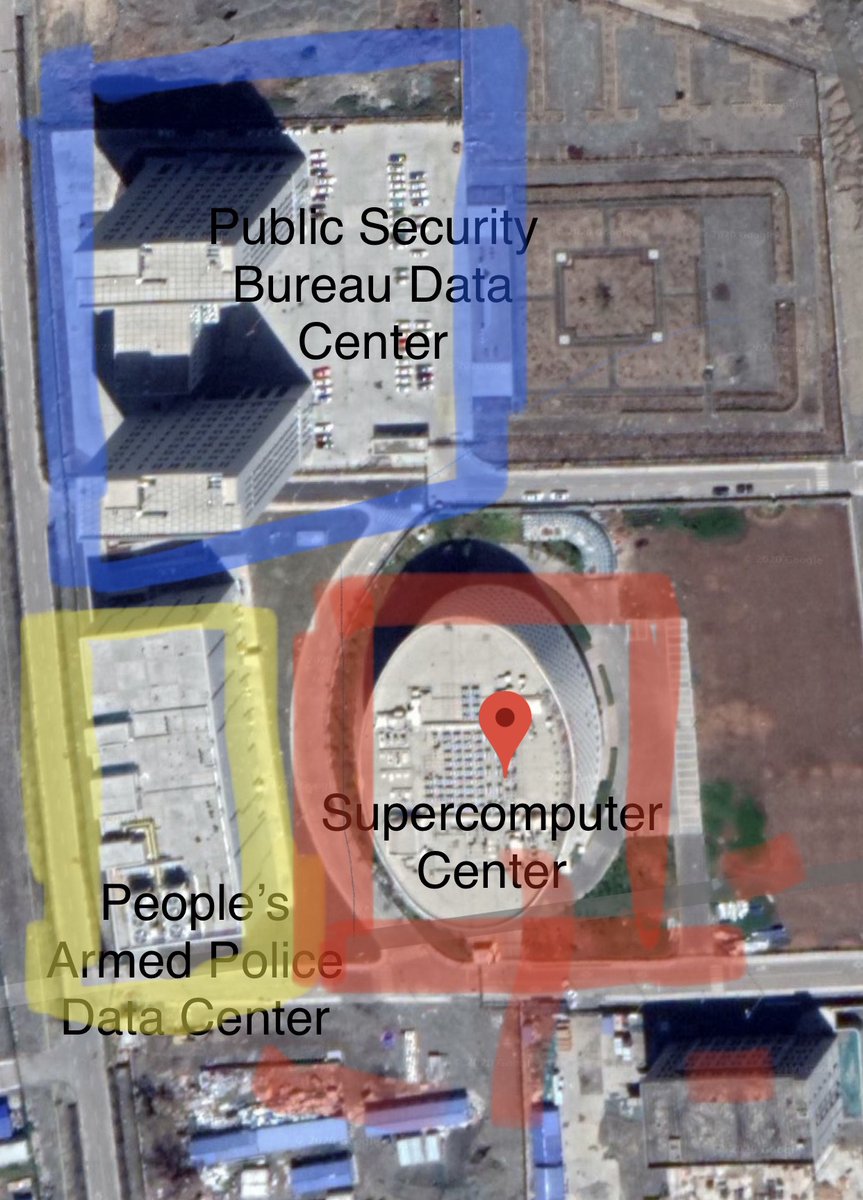

Top-end Nvidia and Intel chips helped the machine rank 135th fastest in the world in 2019. In the past two years the People's Armed Police and Public Security Bureau have built regional data centers next door, likely to cut latency as it crunches huge reams of surveillance data.

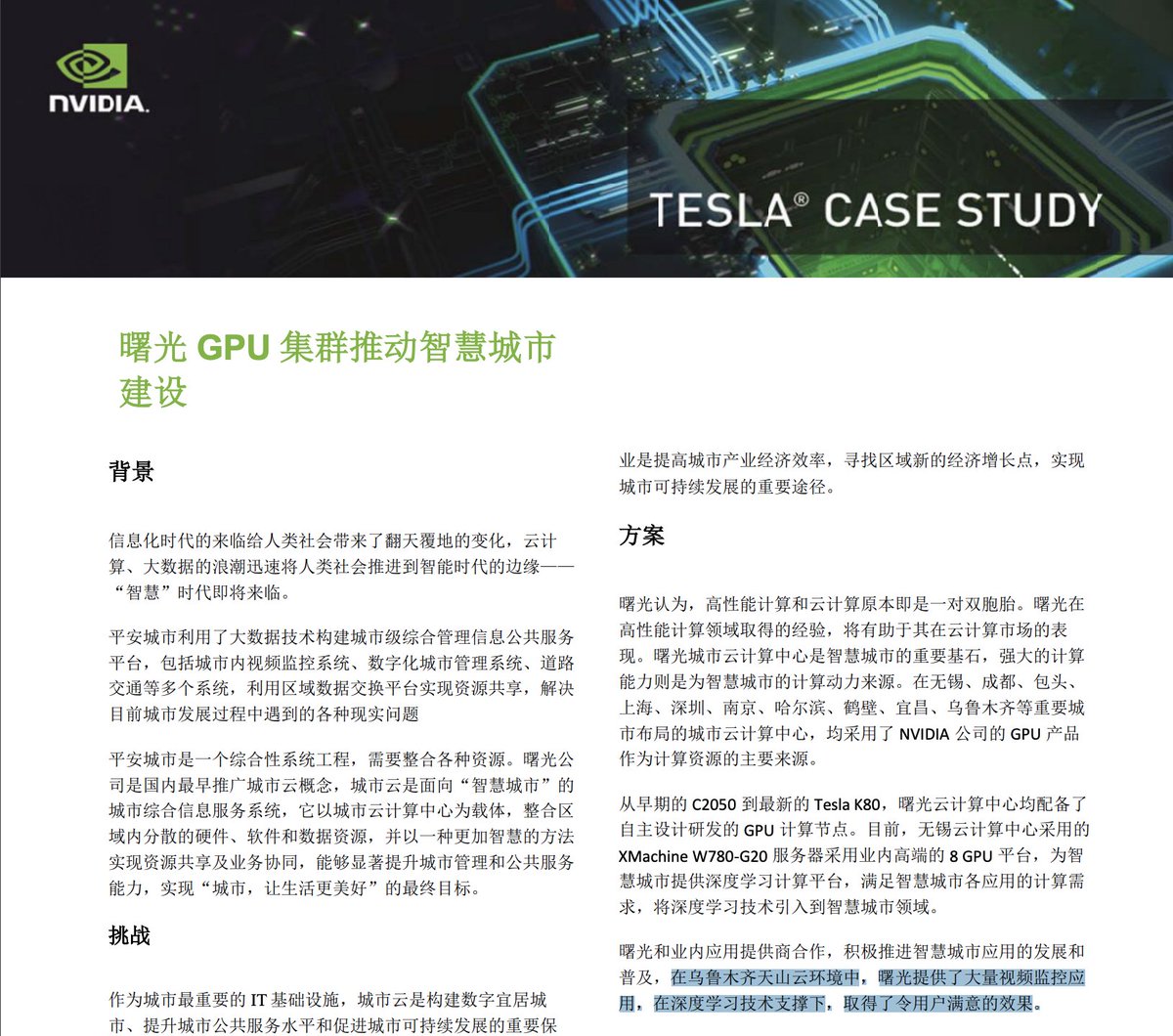

So what can this machine do? According to Sugon, the contractor that made it, as of 2018 it could connect to 10k video feeds an analyze 1,000 simultaneously. A gov't post said it could query 100 mln photos in a second. That made it the best image/video analysis machine in China.

The computer is repeatedly linked to "predictive policing." In practice in Xinjiang that has meant sweeping people up based on their religious activities, travel history, and personal tech choices, like whether a person owns two phones or no phone. nytimes.com/2019/05/22/wor…

Intel and Nvidia said they were unaware of the supercomputer's uses, though there's plenty of public documentation. In 2015 marketing material Nvidia said the Urumqi computing system's surveillance applications had led to high customer satisfaction.

Nvidia and Intel characterized the center as an abuse of their tech. After the Trump admin added Sugon to the entity list Intel stopped selling high-end chips and Nvidia stopped offering technical support. But both still do business with Sugon.

While the scale of Beijing's surveillance build out has caught many by surprise. It's worth remembering not so long ago execs like Nvidia co-founder Jensen Huang saw huge business opportunities in Beijing's push towards a surveillance state. Many still do.

A key question facing a Biden admin is what to do w/ the entity listings the Trump admin set up. They are very imperfect, yet they did stop some biz to cos like Sugon. Some, like Jason Matheny, a former U.S. intel official, call for more tracking of chips to enable smarter blocks

A real question is whether tech sales should be treated like weapon sales. Esp as supercomputers get better at pop. scale surveillance. It’s only a matter of time before China produces its own solutions, which means this course for the future use of tech has already been charted.

This is the last story I was able to do on the ground reporting for in China. I was followed by multiple cars of plainclothes police to the supercomputer. But without that visit, I never would have found the police data center next door. We lose a lot by not being there.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh