Following the sentencing of Eltiona Skana, the woman who killed 7-year-old Emily Jones, a brief [THREAD] on what the sentence means.

bbc.co.uk/news/uk-englan…

bbc.co.uk/news/uk-englan…

Skana pleaded guilty to manslaughter by reason of diminished responsibility. The prosecution dropped (“offered no evidence on”) the charge of murder after developments at trial relating to the psychiatric evidence. More detail on that here:

https://twitter.com/barristersecret/status/1334900002339086338

Manslaughter by diminished responsibility, put simply, means that the legal ingredients for murder are present, but that there are serious mental health issues that reduce (although of course don’t extinguish) culpability. So the law provides for this compromise.

Sentencing for manslaughter by diminished responsibility is not straightforward. Often the court will be having to decide between a sentence that keeps a defendant in hospital, or a sentence that puts them in prison. It involves extensive psychiatric evidence and legal argument.

In short, there are three options open to the court:

1. A hospital order (with or without restrictions)

2. Custody

3. A hybrid order

A hospital order is purely for treatment/rehabilitation.

Custody is for punishment.

A hybrid combines the two. That’s what we have here.

1. A hospital order (with or without restrictions)

2. Custody

3. A hybrid order

A hospital order is purely for treatment/rehabilitation.

Custody is for punishment.

A hybrid combines the two. That’s what we have here.

A hospital order might be suitable in a case where a defendant’s culpability is very low because of a condition over which they have no control. In that case, punishment - prison - may not be just.

But in other cases, culpability might be high, notwithstanding mental ill health.

But in other cases, culpability might be high, notwithstanding mental ill health.

If a judge finds that a hospital order may be appropriate, he must consider whether a “hybrid” order is suitable.

This means a defendant remains in hospital indefinitely until deemed fit and safe for discharge, and is then transferred to prison to serve the rest of her sentence.

This means a defendant remains in hospital indefinitely until deemed fit and safe for discharge, and is then transferred to prison to serve the rest of her sentence.

The idea is that it combines therapeutic and punitive elements for offences where it would not be right for a defendant to escape custody.

In such cases, the defence might argue for a “pure” hospital order and against a hybrid order. That seems to be what happened here.

In such cases, the defence might argue for a “pure” hospital order and against a hybrid order. That seems to be what happened here.

The decision making process that the court must go through is set out in case law. (A hybrid order is referred to as a “section 45A”):

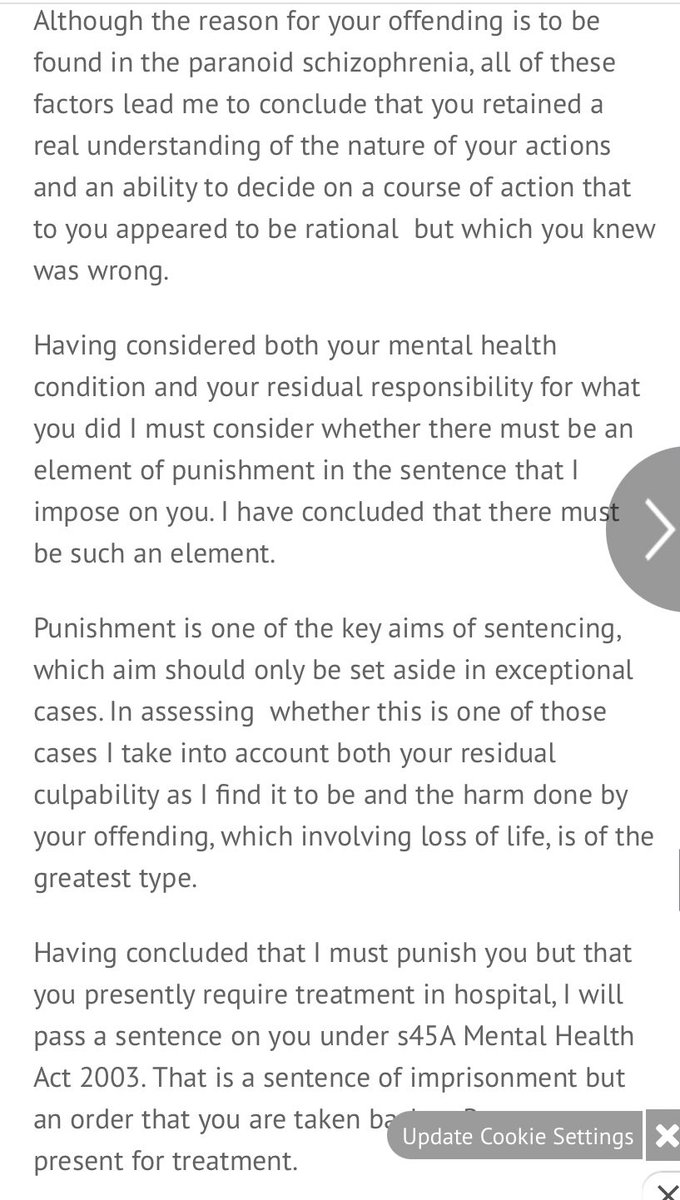

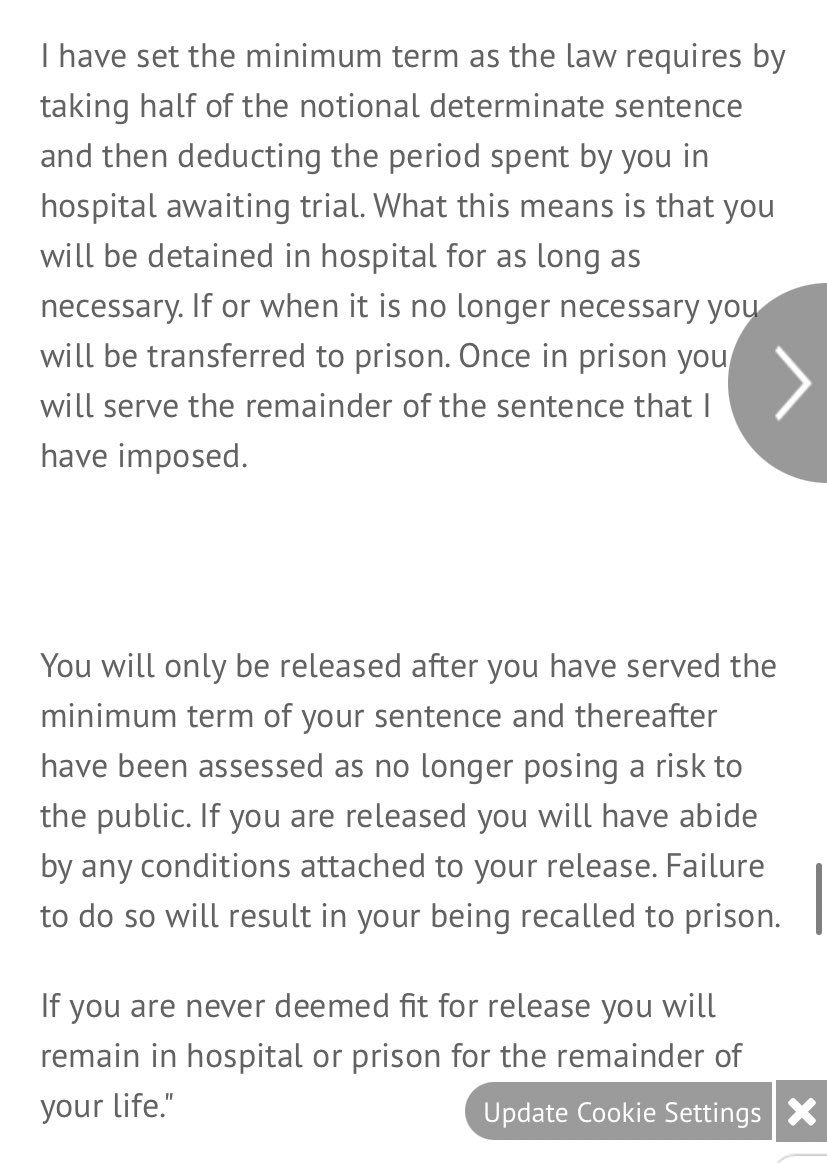

In Skana’s case, the judge imposed a life sentence, with a minimum term of 8 years. Although she was seriously unwell, she was still held highly culpable for her offending.

So a hospital order alone would not have imposed sufficient punishment.

So a hospital order alone would not have imposed sufficient punishment.

But because of her illness, a section 45A order was made. This means that she remains in hospital until either a Mental Health Tribunal or the Justice Secretary deem that she no longer presents a risk to the public or needs treatment.

This could be forever.

This could be forever.

If Skana did become well enough to be discharged, the prison sentence then kicks in. Life with a minimum term of 8 years means you are eligible to apply to the parole board after serving 8 years. If you no longer present a serious risk to the public, you may be released.

Time spent in hospital counts towards the prison sentence. So if she spent more than 8 years in hospital, she should be referred to the parole board once discharged from hospital.

If Parole Board deem her safe ➡️ release on licence.

If not, she stays in prison.

If Parole Board deem her safe ➡️ release on licence.

If not, she stays in prison.

But - and this is the part to repeat given a lot of public confusion - there is no guarantee Skana will ever be discharged.

And even if discharged, there is no guarantee she will ever be released from prison.

And even if discharged, there is no guarantee she will ever be released from prison.

So having decided it was a hybrid order (s45A), the judge looked at the prison element. Because of the risk, he found that a life sentence was necessary.

A life sentence comprises a “minimum term” after which you can apply for parole. If released you are on licence for life.

A life sentence comprises a “minimum term” after which you can apply for parole. If released you are on licence for life.

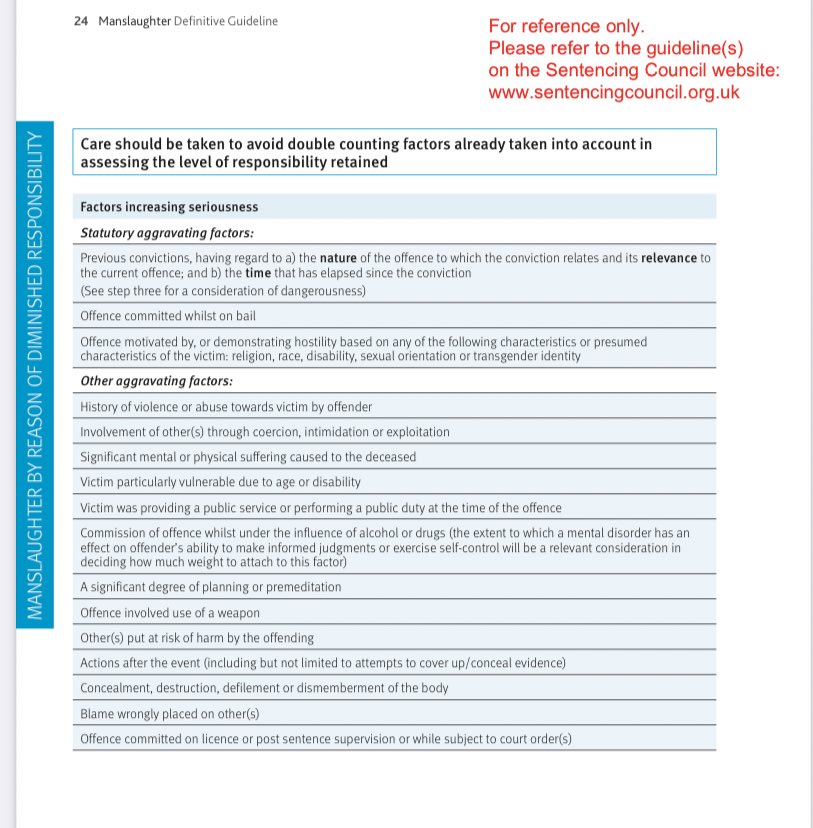

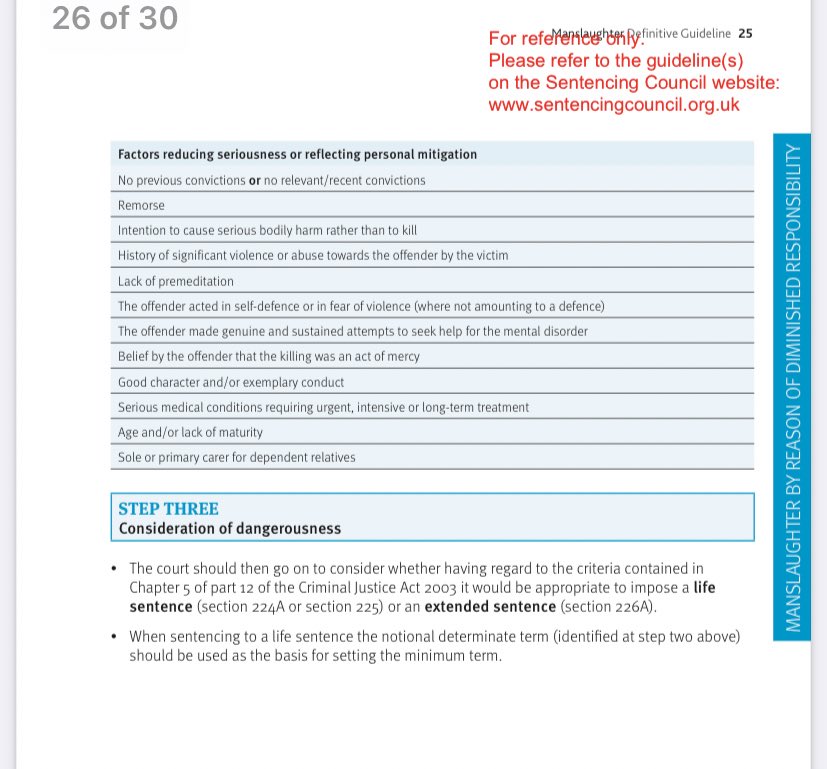

How did the judge arrive at a minimum term of 8 years? He applied the sentencing guidelines. It seems that this was a case of high culpability. She would be entitled to credit for her guilty plea.

Because this is a life sentence, that figure is then reduced to reflect the fact that, if it was a determinate sentence, there would be the prospect of release at the halfway or two-thirds stage of the sentence. So you reduce it some more to get to 8 years.

This all sounds pretty vague. That’s because, even though this is a huge case that has caused enormous public confusion, the judge’s sentencing remarks have STILL, nearly 24 hours later, not been published. So we don’t know his thinking.

The justice system simply must do better.

The justice system simply must do better.

For those suggesting the sentence is “soft” - it’s not. It is probably the most oppressive type of sentence a court can pass, setting a very high test for release from hospital, and then again to be released from prison. And then being on licence and subject to recall for life.

None of this, of course, can for a moment relieve the grief of Emily’s family. What they have been through does not bear imagination. But sadly no sentence can be passed to undo what has happened. The criminal justice system can often feel hollow in cases like this.

UPDATE;

I’m grateful to @TozerJ for alerting me to this. Although the judge’s sentencing remarks haven’t been published officially on the @JudiciaryUK website, they have been faithfully reproduced by @MENnewsdesk here.

manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-m…

I’m grateful to @TozerJ for alerting me to this. Although the judge’s sentencing remarks haven’t been published officially on the @JudiciaryUK website, they have been faithfully reproduced by @MENnewsdesk here.

manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-m…

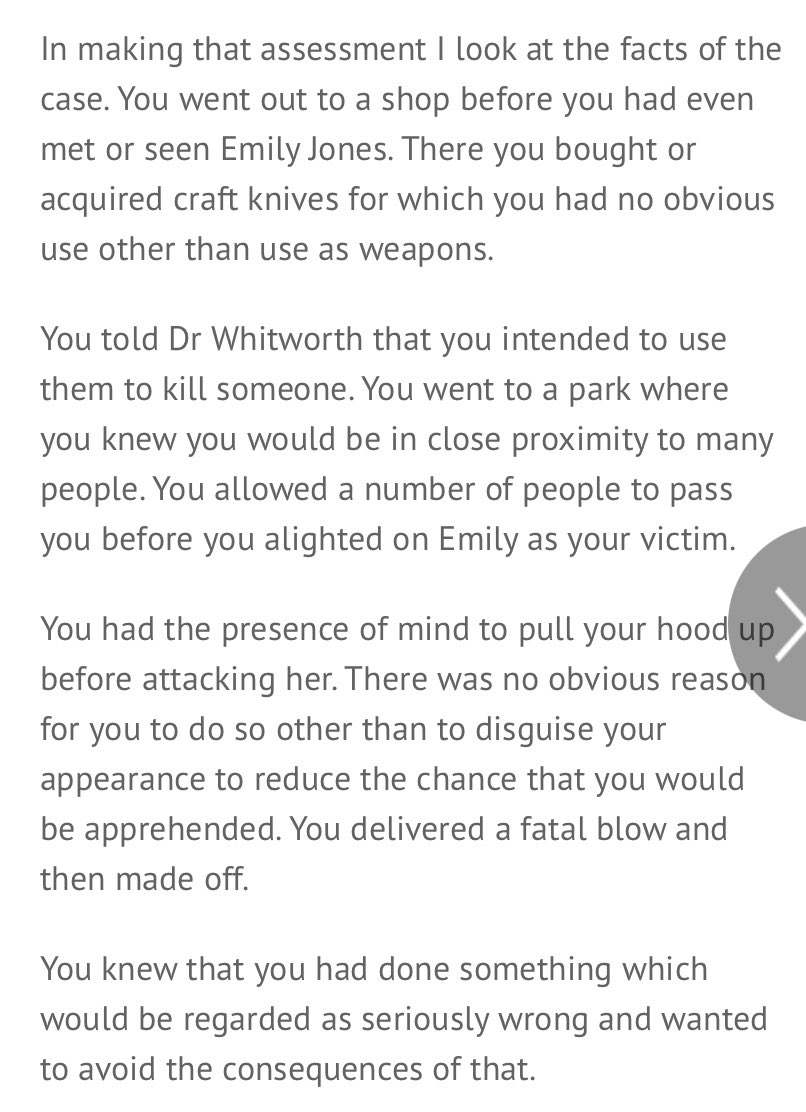

The judge dealt fully with the issue of culpability - he assessed it as “significant”, for these reasons. This also explains why he considered that a hospital order alone, without prison, was not appropriate, and why a “hybrid” s45A order was right.

This was the judge’s approach to the Sentencing Guideline.

In short, medium culpability with serious aggravating features = 24 years

One third credit for guilty plea (as required by law) = 16 years

Life sentence, so halve to arrive at minimum term = 8 years.

In short, medium culpability with serious aggravating features = 24 years

One third credit for guilty plea (as required by law) = 16 years

Life sentence, so halve to arrive at minimum term = 8 years.

A final, tangential comment.

I spend a lot of time (and a book or two) criticising poor reporting of legal stories and court cases. The reporting of this difficult and complex case by @TheBoltonNews and @MENnewsdesk has been exemplary. Detailed, accurate and fair.

I spend a lot of time (and a book or two) criticising poor reporting of legal stories and court cases. The reporting of this difficult and complex case by @TheBoltonNews and @MENnewsdesk has been exemplary. Detailed, accurate and fair.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh