Fact 16: Akkadian (Babylonian, Assyrian) cuneiform and Japanese writing system have surprisingly many common features. In this short thread we’ll show some of them. #AdventCalendar

Basics of Akkadian & Japanese

- both mix logograms (word signs) & phonetic signs

- both write syllables, not invidual sounds

-…but neither is purely syllabic, often you need two signs for one syllable

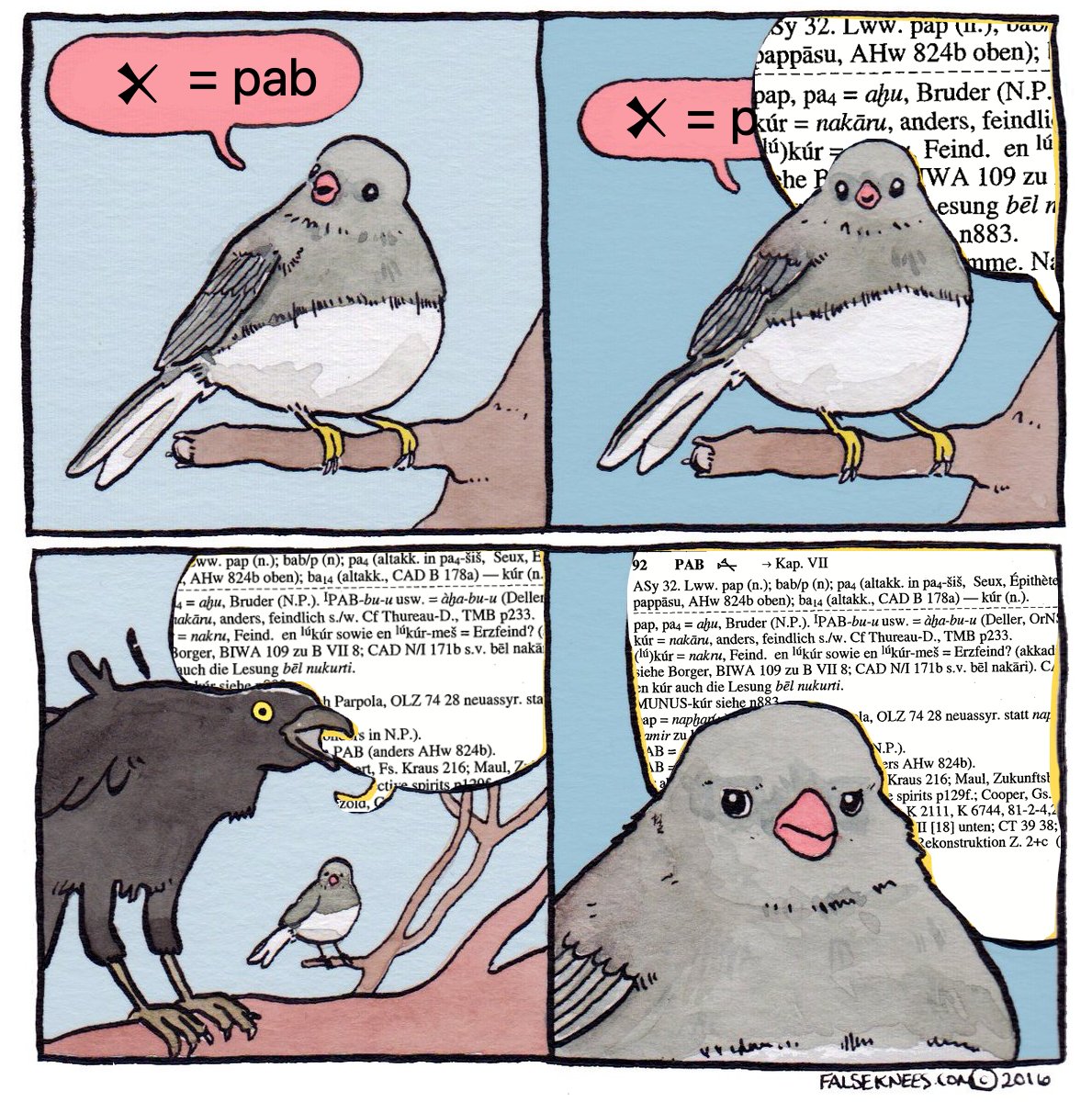

- both have signs which can be read in more than one way, depending on context

- both mix logograms (word signs) & phonetic signs

- both write syllables, not invidual sounds

-…but neither is purely syllabic, often you need two signs for one syllable

- both have signs which can be read in more than one way, depending on context

And why? Basically, because Japanese and Akkadian speakers both borrowed their writing system from a people speaking a completely different language, Japanese from Chinese and Akkadian from Sumerian, both being the first written languages in the area.

Sumerian and Chinese are mostly logographic, meaning that one sign = one word (more precisely, a morpheme). All the important content words have their own signs, same with important function words (prepositions etc). What happens when you try to borrow this to another language?

Different languages have different lexicon and different grammar. They have words which simply don’t exist in the other language. Sumerian doesn't mark gender, Akkadian does. Chinese verbs don't have tenses (past, present etc), Japanese verbs have. And so on.

Both Japanese and Akkadian speakers needed a way to write things which didn’t exist in the language they took their script from. Both scripts took a similar path: introducing more and more phonetic signs, signs used only for the sound, not meaning (like the alphabet).

The phonetic signs didn’t appear out of the blue. New language users just started to use existing signs in new ways. First, Japanese speakers just used Chinese characters ”as is”, but frequently phonetically used signs started to simplify & modern kana syllabaries started to form

Akkadian writers didn’t go that far, same signs continued to be used both as logograms and phonograms. But similar processes happened also there. One sign often had several readings, some coming from Sumerian, some based on how Akkadians pronounced the word with similar meaning.

A complicated and beautiful mess was born. Akkadian cuneiform was slowly replaced by alphabetically written Aramean, and a bit similar thing happened in Korea when Chinese characters were replaced by the hangul syllabary. But the Japanese writing is very much living still today.

If you like (or hate in a loving way) Japanese, you’d probably enjoy learning cuneiform. If you like cuneiform, you’d probably enjoy learning Japanese.

Since I already knew Japanese when I started to learn Akkadian, I naturally spotted these things. However, things mentioned in this thread are also noted by researchers: at least Jun Ikeda and Timothy Vance have compared Japanese&Akkadian, so take a look on their work, too!

Pictures 1, 2, 5, 6 and 8 are from the Wikimedia Commons, others are taken/edited by us :)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh