One of Germany’s most prominent economists, Hans-Werner Sinn, warns of hyperinflation; he links it directly to Hitler's rise to power. A distortion of history: the rise of the Nazis was preceded by deflation, exacerbated by fiscal austerity. Thread /1

braveneweurope.com/philipp-heimbe…

braveneweurope.com/philipp-heimbe…

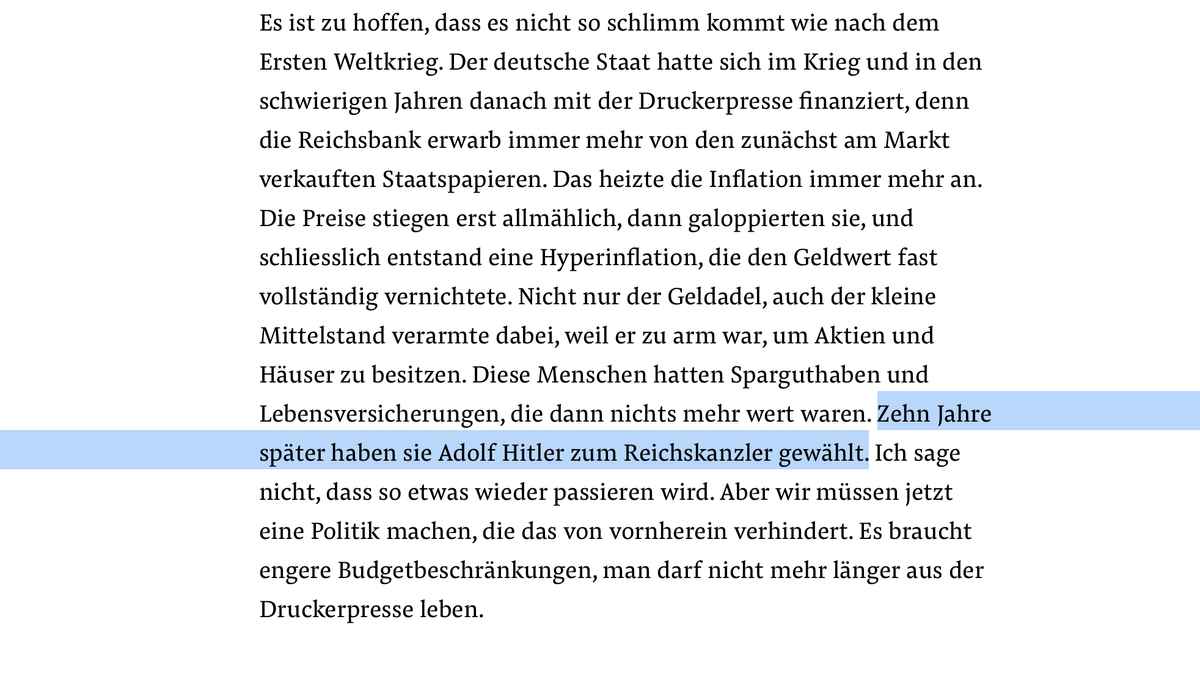

Sinn says hyperinflation after WW1 impoverished the German middle class in the Weimar Republic: "Ten years later they elected Adolf Hitler as Reich Chancellor." Policy recommendation today against hyperinflation: "tighter budget constraints" /2

nzz.ch/finanzen/hans-…

nzz.ch/finanzen/hans-…

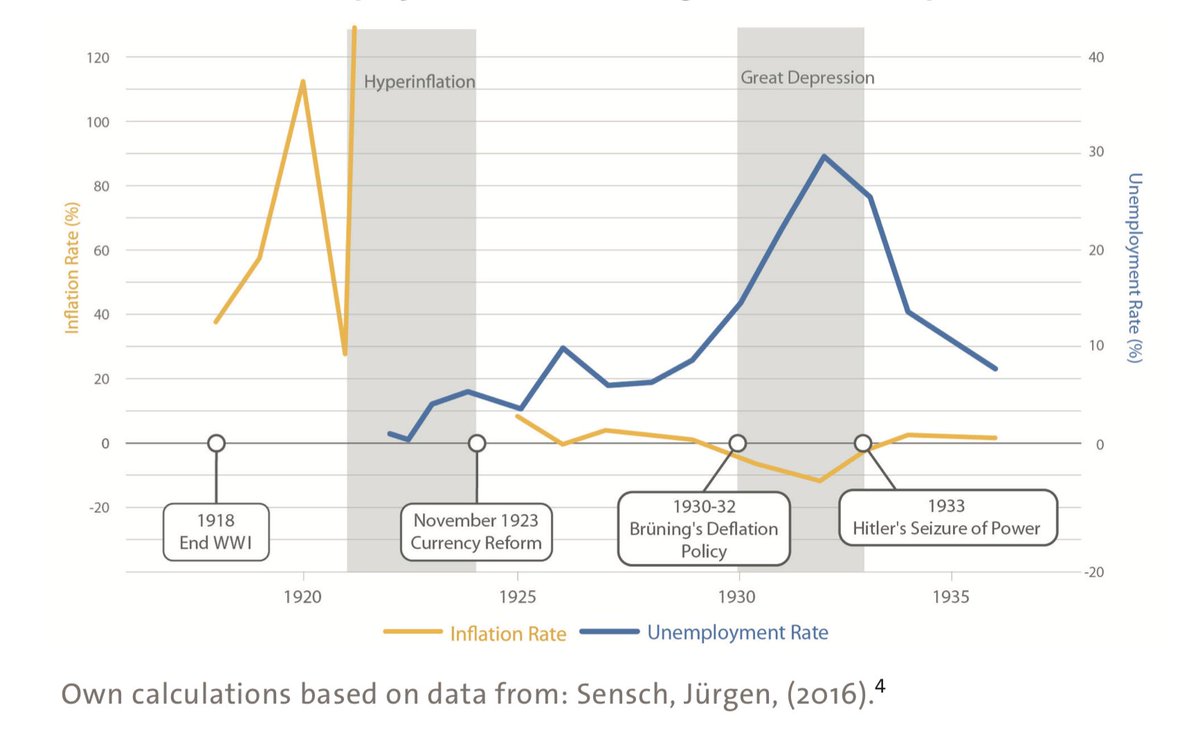

Sinn thus feeds a widespread misinterpretation. Mass poverty when the Nazis came to power in 1933 was not the result of hyperinflation, which at that time was ten years in the past; it was primarily a consequence of mass unemployment due to the recession in the early 1930s. /3

The Nazis had come to power after years of deflation - i.e. falling prices. From 1930 onwards, Reich Chancellor Brüning used emergency decrees to bring about tax increases and drastic state spending cuts that pierced the social safety net. /4

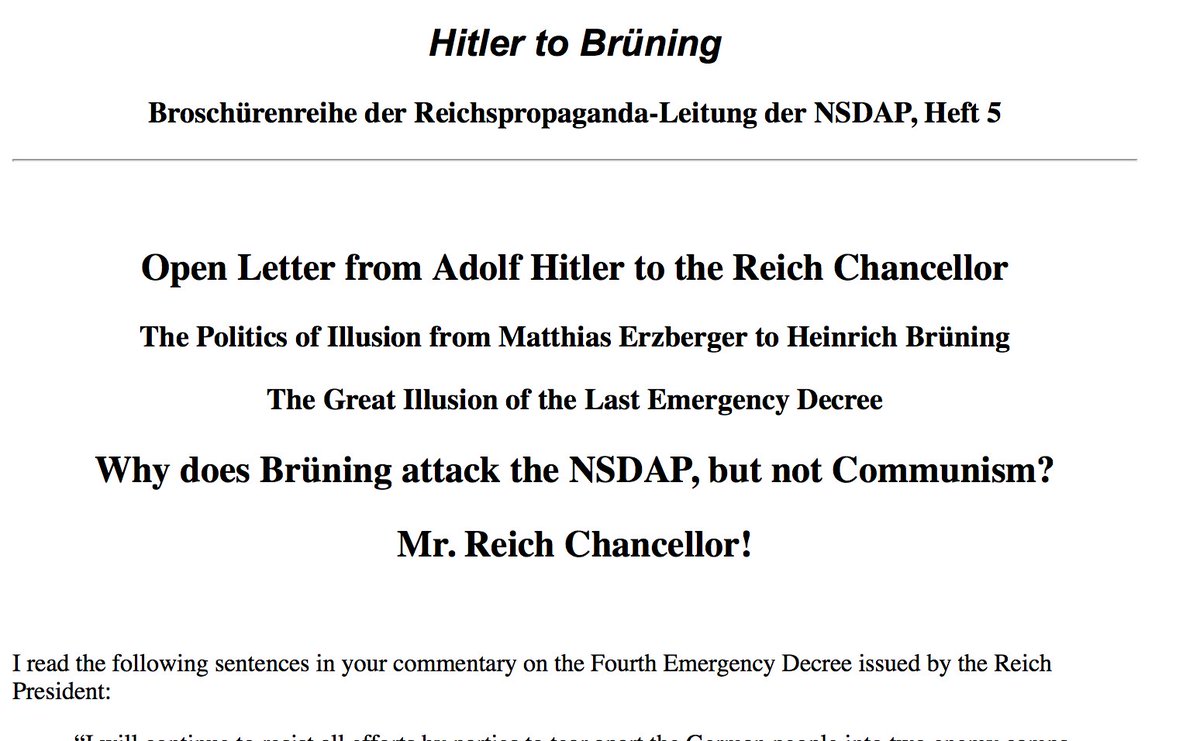

Austerity policies increased unemployment, led to social suffering and unrest. Hitler realised by the end of 1931 at the latest that Brüning's austerity policy would "help his party to victory and thus end the illusions of the present system." /5

research.calvin.edu/german-propaga…

research.calvin.edu/german-propaga…

Analysis of data from four elections between 1930 and 1933 shows that voters in areas more affected by spending cuts and tax increases gave significantly more votes to the National Socialists, supporting Hitler’s rise./6

voxeu.org/article/fiscal…

voxeu.org/article/fiscal…

HW Sinn calls for "tighter budget constraints" against hyperinflation after Corona. Dangerous distortion: he does not say a word about the link between the negative effects of austerity policies in the early 1930s and Hitler's rise to power. /7

Representative survey: Only 1 in 25 Germans today still knows that the crisis at that time was characterised by deflation. Almost half of the respondents - like HW Sinn - mix mass unemployment and deflation with the hyperinflation ten years earlier./8

hertie-school.org/fileadmin/user…

hertie-school.org/fileadmin/user…

Incidentally, this misconception is much more common among well-educated and politically interested Germans. Those who are following the ECB’s monetary policy closely are more likely to draw the wrong lessons from history and to be misled by HW Sinn. /9

Even if one were to agree with Sinn that hyperinflation "prepared the breeding ground for the Nazis", his comparisons would remain problematic: why should the ECB’s monetary policy today lead to hyperinflation similar to the early 1920s? /10

handelsblatt.com/meinung/kolumn…

handelsblatt.com/meinung/kolumn…

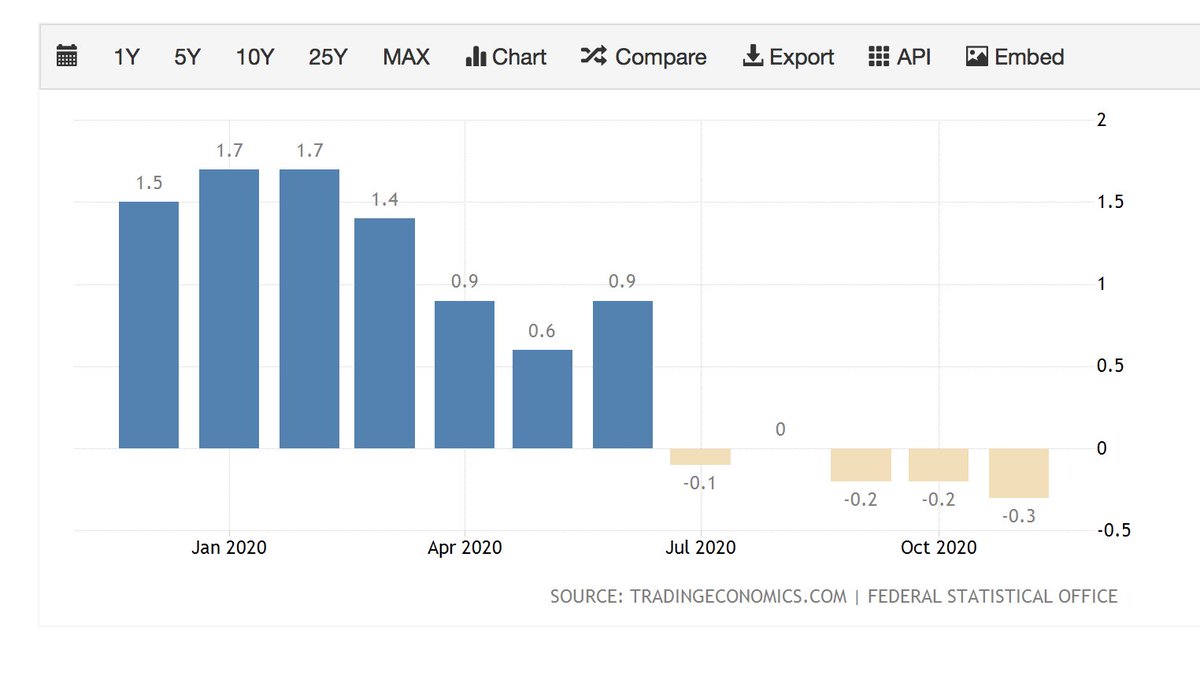

The ECB is not directly financing governments, as the Reichsbank did back then. Even in Germany, inflation rates have been negative recently. Sinn remains unconcerned about deflation, stressing risks of hyperinflation, although previous inflation warning have not materialised /11

Misinterpretations of history can be momentous if they lead economic policy down the wrong track. To prevent this, prominent economists must not go unchallenged when they fuel such dangerous misconceptions. /end

.@HansWernerSinn did it again: in his "Christmas Lecture", he warns of hyperinflation.He draws a direct line from hyperinflation in 1923 to the Nazis (which doesn't exist), fails to mention that Nazi rise was preceded by deflation, worsened by austerity.

In his reply to my comment, Sinn claimed that he saw the role of austerity measures similarly to me, but that he could not mention everything in an interview. In 73 minutes of "Christmas Lecture" he again did not mention deflation and fiscal austerity.

handelsblatt.com/meinung/kolumn…

handelsblatt.com/meinung/kolumn…

Sinn did not retreat from his economic policy conclusions for today ("tighter budget constraints", "no longer living off the printing press") - even if these are not compatible with his seeing a truly significant role for austerity in Nazi rise.

In his "Christmas Lecture" @HansWernerSinn again warns of hyperinflation with shrill words: "money flood"; "dramatic inflation of the money supply"; "ECB as a gold donkey".

Is this an appropriate way to deal with the subject - even if it is addressed to non-economists?

Is this an appropriate way to deal with the subject - even if it is addressed to non-economists?

While Sinn's historical excursions are analytically expandable, they primarily aim at arousing emotions. Sinn talks about how money, like paper, was no longer worth anything in 1923, and shows a girl who had made a dress out of worthless banknotes.

Given the way Sinn spins things rhetorically, listeners are tempted to fear hyperinflation. Of course, hyperinflation won't come right away - but "what if the coachman can't find the reins" once it gets going?

"The €zone is not different from the monetary systems of earlier times. The potentates succumb to the temptation of using the printing press."-Thus @HansWernerSinn concludes his lecture.

Or has HWS succumbed to the lure of warning with historical distortions and thin arguments?

Or has HWS succumbed to the lure of warning with historical distortions and thin arguments?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh