Having now taken a few days to digest the detail of the UK-EU agreement, here's a couple of observations from me on the deal, what it means, how we got here, & where it might take future UK-EU relations.

(A long thread)

(A long thread)

First, let's be clear that negotiating a deal in 9 months, against the odds, and in the middle of a pandemic, is an achievement. It's too easy to underestimate the difficulty of negotiating over the screen for 4 months, from Mar-June, and under enormous pressure. /2

Both @DavidGHFrost & @MichelBarnier and their teams, deserve a lot of credit for sticking up with it in hard circumstances, often with lacking political clarity, & high stakes.

This shouldn't preclude us, or MPs and MEPs, from looking critically at the deal on the table. /3

This shouldn't preclude us, or MPs and MEPs, from looking critically at the deal on the table. /3

That we have a deal is a result of the UK & EU having found a way to protect their core defensive interests.

From the EU's view, integrity of the single market is preserved with level-playing field obligations which go virtually beyond any other 3rd-country (even the Swiss). /4

From the EU's view, integrity of the single market is preserved with level-playing field obligations which go virtually beyond any other 3rd-country (even the Swiss). /4

For its part, the UK has negotiated down EU ask on dynamic alignment on state aid; eliminated any references to EU law; removed any role for the ECJ (NB not in the whole future relationship, due to EU law in NI Protocol); and preserved its right to control access to waters. /5

If you look at the deal through the lens of defensive interests, you'll see a victory no matter on which side you stand.

This negotiation was about defensiveness: protecting "sovereignty" on the UK side and "integrity of the single market" on the EU side, and at any price. /6

This negotiation was about defensiveness: protecting "sovereignty" on the UK side and "integrity of the single market" on the EU side, and at any price. /6

The compromise on LPF is, in my view, reasonable. On state aid, it includes a commitment to domestic regimes on both sides, with enforcement. Domestic courts should be allowed to review subsidy decisions.

This is far more than UK initial position, but less than the EU’s ask. /7

This is far more than UK initial position, but less than the EU’s ask. /7

The non-regression on environmental, labour and social rules is less binding than expected (no arbitration), but it includes commitment to domestic enforcement.

Again, a reasonable compromise, but closer to the EU position than the UK's. /8

Again, a reasonable compromise, but closer to the EU position than the UK's. /8

What is novel is the "rebalancing mechanism": what happens if there’re “significant divergences” across the LPF in a way that materially affect bilateral trade or investment.

The scope is wide: it applies to any future subsidies, or labour/social, or envi/climate protections. /9

The scope is wide: it applies to any future subsidies, or labour/social, or envi/climate protections. /9

If such divergences are found, either party can take unilateral temporary "rebalancing measures" (eg tariffs), based on "reliable evidence" rather than "conjecture".

Importantly, the right to impose rebalancing measures is symmetrical (both sides can use it), and /10

Importantly, the right to impose rebalancing measures is symmetrical (both sides can use it), and /10

subject to the proportionality test before arbitration. If rebalancing measures are deemed unjustified, the other party can take countermeasures.

The two principles are just what I proposed several weeks ago as a way to break the deadlock. /11

The two principles are just what I proposed several weeks ago as a way to break the deadlock. /11

https://twitter.com/AntonSpisak/status/1337830029909258241

I think the compromise is reasonable, and I'm glad that sensible minds prevailed in the negotiating room, though I'm a bit doubtful about its functionality, since it could escalate into a tit-for-tat conflict.

Fortunately, there's a review clause after 4 yrs. /12

Fortunately, there's a review clause after 4 yrs. /12

On governance, the UK secured a concession over removing concepts of EU law from the treaty, as well as role for the ECJ in dispute resolution.

Otherwise, it has folded completely. It accepted a single legal treaty that it had vehemently opposed at the outset; /13

Otherwise, it has folded completely. It accepted a single legal treaty that it had vehemently opposed at the outset; /13

a single governance system; a horizontal dispute settlement mechanism, with possibility of cross-retaliation (restricted to the trade parts of the deal); and robust enforcement provisions on LPF; and provisions on ongoing compliance with the ECHR. /14

On fisheries, there're others more qualified to assess the deal (see John's excellent take below).

I'd note one aspect where the UK has conceded: dispute resolution & cross-retaliation (there can be tariffs if there's no future agreement on quotas). /15

I'd note one aspect where the UK has conceded: dispute resolution & cross-retaliation (there can be tariffs if there's no future agreement on quotas). /15

https://twitter.com/john_lichfield/status/1342832551552049153

It's too easy to look at the deal through the lens of defensive interests and conclude it's the best we could get.

In my view, what matters in assessing the quality of a deal is not only the obligations, but also the rights it gives and the balance btwn rights & obligations. /16

In my view, what matters in assessing the quality of a deal is not only the obligations, but also the rights it gives and the balance btwn rights & obligations. /16

If we look at the rights, the deal doesn't bode that well.

True, it provides access without tariffs and quotas (fow now, and s.t. goods qualifying for zero tariffs).

Plus, helpful provisions on air and road transport & energy; which are all a function of UK-EU proximity. /17

True, it provides access without tariffs and quotas (fow now, and s.t. goods qualifying for zero tariffs).

Plus, helpful provisions on air and road transport & energy; which are all a function of UK-EU proximity. /17

But my biggest concern with this deal is that the substantive provisions in the trade part fall even below the standard of recent EU FTAs. It's disappointing and, what's more, makes the overall deal look pretty unbalanced.

Here're several notable examples. /18

Here're several notable examples. /18

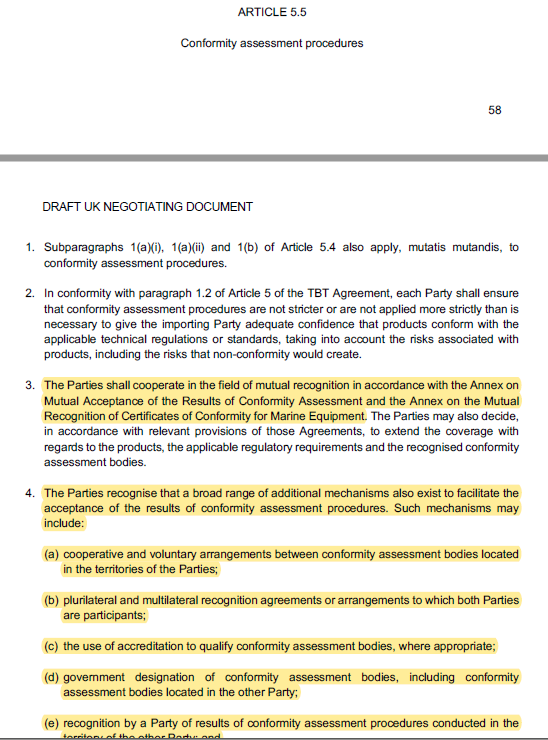

1. Mutual recognition of conformity assessment.

The EU agreed it (in limited way) with Canada, US, Switzerland, etc. The UK asked for It in its initial offer (see below).

With the exception of a handful of sectoral annexes, you won’t find it in the final deal. /19

The EU agreed it (in limited way) with Canada, US, Switzerland, etc. The UK asked for It in its initial offer (see below).

With the exception of a handful of sectoral annexes, you won’t find it in the final deal. /19

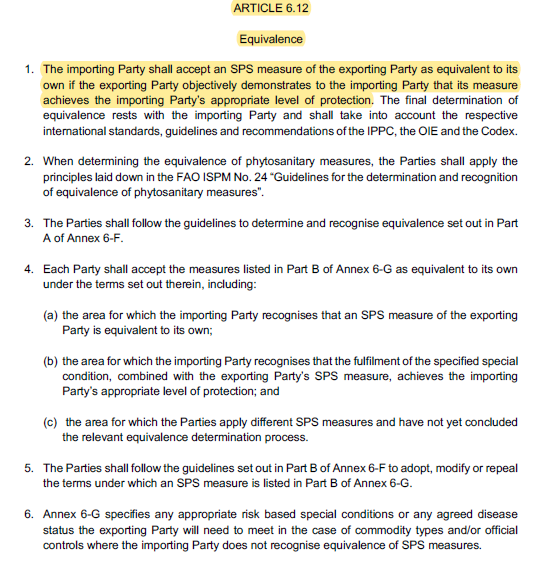

2. A mechanism for recognising equivalence for sanitary and phytosanitary measures (SPS).

The same. The EU agreed with Canada, Japan, and proposed it to AUS/NZ.

Search for it in the deal, but you won’t find it. With implications for trade between GB and NI. /20

The same. The EU agreed with Canada, Japan, and proposed it to AUS/NZ.

Search for it in the deal, but you won’t find it. With implications for trade between GB and NI. /20

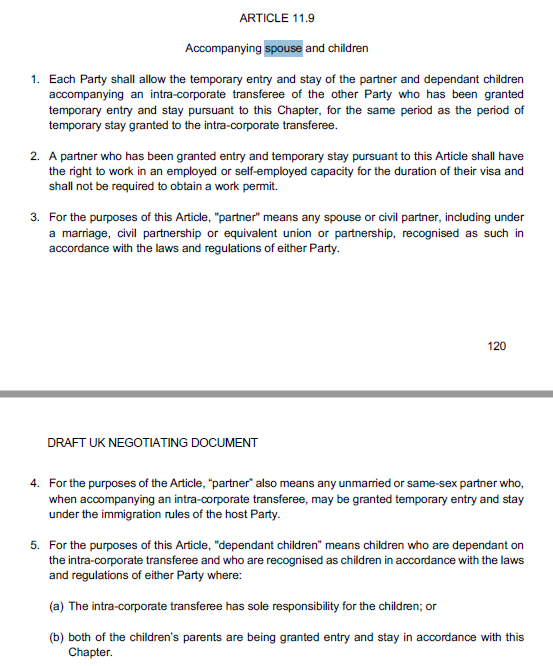

3. Provisions for services. Significantly watered down from initial texts.

The final offer on temporary movement of business visitors (Mode 4) is less generous than EU-Japan.

Also, forget about accompanying spouses, children, etc, that the UK had proposed initially. /21

The final offer on temporary movement of business visitors (Mode 4) is less generous than EU-Japan.

Also, forget about accompanying spouses, children, etc, that the UK had proposed initially. /21

4. No regulatory provisions for financial services.

This isn't about equivalence, but about ongoing cooperation. It can be found in EU-Japan. Forget about it here.

There'll be a non-binding MoU next year.

(Btw, this, from Sunak, is embarrassing) /22

theguardian.com/politics/2020/…

This isn't about equivalence, but about ongoing cooperation. It can be found in EU-Japan. Forget about it here.

There'll be a non-binding MoU next year.

(Btw, this, from Sunak, is embarrassing) /22

theguardian.com/politics/2020/…

Just four examples, many others in the deal. But they are really important: some of them (services) reflect not just important UK offensive interests, but also, I'd have thought, areas of shared interest (SPS equivalence).

They were all dropped from the negotiation. /23

They were all dropped from the negotiation. /23

The bottom line is that, as soon as you look at this deal through the lens of the rights it provides, it's very thin. It falls even below the standard of recent EU FTAs.

This is really disappointing to see, but I fear it is a reflection of the politics of this negotiation. /24

This is really disappointing to see, but I fear it is a reflection of the politics of this negotiation. /24

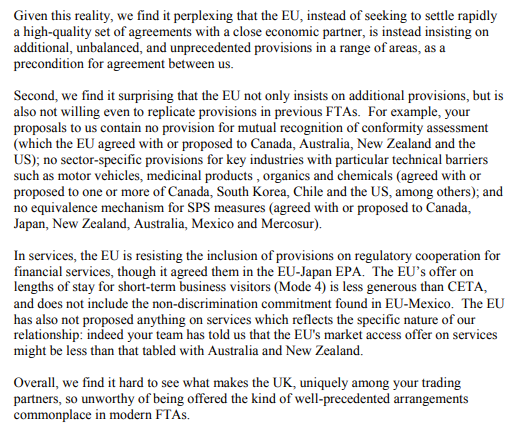

This, by the way, is exactly what Frost complained about to Barnier in his letter on 19 May. Seven months later, it is - expect for limited sectoral annexes on medicines, motor vehicles and medicines - the final deal. /25

As a result, we've ended up with a minimal deal – a least-common-denominator deal – but one with more stringent obligations, particularly on level-playing field, than any other trade agreement. /26

Why did we end up here?

My view is that the UK made a strategic miscalculation when it dropped most of its offensive asks in the hope of winning the argument over LPF. It didn't win, and ended up with a thin deal.

I warned about this in the summer. /27

institute.global/policy/uk-fall…

My view is that the UK made a strategic miscalculation when it dropped most of its offensive asks in the hope of winning the argument over LPF. It didn't win, and ended up with a thin deal.

I warned about this in the summer. /27

institute.global/policy/uk-fall…

(A reminder that Gove went as far as suggesting the UK would be prepared to accept a deal with tariffs if it means "Canada-style" obligations on LPF. A complete misjudgement of EU position and a miscalculation for what would happen in the endgame.) /28

independent.co.uk/news/uk/politi…

independent.co.uk/news/uk/politi…

Another reason, perhaps, is that the EU's initial text, rather than the UK's, was used for drafting the final text. As a result, the eventual deal is much closer to the EU's offer. This isn't just a question of form, but it's also reflected in substance, as I explained above. /29

We're where we're. For all this, there is no question that this deal is better no deal. It is.

Its biggest value, beyond avoiding the short-term economic & political cost of no-deal, is that it offers a starting point for the UK & EU to revisit their relationship in future. /30

Its biggest value, beyond avoiding the short-term economic & political cost of no-deal, is that it offers a starting point for the UK & EU to revisit their relationship in future. /30

I doubt that this deal can be a sustainable basis for future UK-EU relations, for two main reasons:

1. Northern Ireland. The friction to trade between GB and NI will be high, partly as a result of very ambitious regulatory provisions on goods between the UK and EU. /31

1. Northern Ireland. The friction to trade between GB and NI will be high, partly as a result of very ambitious regulatory provisions on goods between the UK and EU. /31

Over time, as SM legislation for goods evolves (and it does so at pace), the regulatory differences between GB and NI will grow.

Govt will face a difficult question whether to voluntarily align to EU SM product and SPS rules to minimise friction, or risk high friction. /32

Govt will face a difficult question whether to voluntarily align to EU SM product and SPS rules to minimise friction, or risk high friction. /32

That, I expect, will create a new, real pressure point not just on Govt, but also on NI institutions when the Assembly votes on NI Protocol, first in 2024.

The real constraint on UK rule-making is more indirect than whatever in this treaty: it's keeping NI close to GB. /33

The real constraint on UK rule-making is more indirect than whatever in this treaty: it's keeping NI close to GB. /33

2. The fact that this deal doesn't meaningfully cover UK offensive interests (esp services) means that the realities of its downsides will be quickly obvious. I expect it'll need to be re-negotiated by a future government at the earliest opportunity. /34

This shouldn't be surprising. It's what happens with 3rd-countries drawn to the EU by its regulatory and economic clout.

Ask the Swiss, who are preparing for renegotiation of their core FTA, or the Turks, who have been renegotiating the FTA and customs agmt for the past yrs. /35

Ask the Swiss, who are preparing for renegotiation of their core FTA, or the Turks, who have been renegotiating the FTA and customs agmt for the past yrs. /35

The challenge will be the UK and the EU having to quickly find new ways of working together.

New structures will need be created to manage the agreement on an ongoing basis (see below on this). /36

New structures will need be created to manage the agreement on an ongoing basis (see below on this). /36

https://twitter.com/AntonSpisak/status/1342898562078793728

And, remember, the UK will still want to influence EU SM legislation, not least because NI will be adopting relevant SM rules for goods trade.

Because there's no consultation procedure for new SM rules in the NI Protocol, it means the UK will need to get on the front foot. /37

Because there's no consultation procedure for new SM rules in the NI Protocol, it means the UK will need to get on the front foot. /37

Over time, I expect this will create big difficulties and these realities will have to be accommodated within NI Protocol (or a new agreement).

I fear, the UK, with all my superb former colleagues in FCO, will find it hard to influence the EU through indirect channels. /38

I fear, the UK, with all my superb former colleagues in FCO, will find it hard to influence the EU through indirect channels. /38

Beyond these on-the-ground difficulties, another key challenge for both sides will be accepting the new reality of regulatory competition.

For all the LPF provisions - and, yes, they are important and significant - the UK and the EU will now become strategic competitors. /39

For all the LPF provisions - and, yes, they are important and significant - the UK and the EU will now become strategic competitors. /39

It's hard to anticipate what the reality of regulatory competition might look like - at least until we find out what Johnson's government decides to do with Britain's newfound freedoms.

What is clear now is that it'll be constrained by 2 factors: /40

What is clear now is that it'll be constrained by 2 factors: /40

1. The gravitational pull of EU regulations ("Brussels effect") for business.

2. Northern Ireland and the need to keep regulatory checks btw GB/NI minimal.

(Btw, this book, rather than Superforcasting, should be a mandatory read for all UK officials) /41

amazon.com/Brussels-Effec…

2. Northern Ireland and the need to keep regulatory checks btw GB/NI minimal.

(Btw, this book, rather than Superforcasting, should be a mandatory read for all UK officials) /41

amazon.com/Brussels-Effec…

All this is why I doubt that this agreement can be a sustainable basis for future relations, partly because of the realities of future NI integration in the SM and partly because of its unbalanced nature (which will be increasingly clear in the years to come). /42

With this agreement, the immediate challenge of Brexit might disappear from the public eye. But its consequences are here to stay: for businesses and the practical realities of new relationship.

Europe, as a political issue, will have a new face but will not go away. /End

Europe, as a political issue, will have a new face but will not go away. /End

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh